OP-ED

(Un)made in South Africa: A nation’s elusive quest for industrialisation

Historians tell us that even at its height, South Africa’s manufacturing was manufacturing only by the strictest definition. Looked at this way, the country’s reputation for past prowess in this area is due for reconsideration.

Since the foundation of the country, every successive South African government has, at least in its rhetoric, sought to make the country a leading industrialised nation. Each has achieved modest results – if any. Simply put, industrialisation refers to an economy’s diversification from agricultural output towards sophisticated manufacturing of products. The primary attraction of industrial activity is that it acts as a major job creator and can help a country carve out its niche in the global value chain.

Industrialisation may be measured by the number of a country’s workforce involved in advanced production; the share of manufactured goods in its total exports; or by the share of the same products in gross domestic product (GDP). At its peak, South Africa’s manufacturing contribution to GDP stood at nearly a quarter. That was in 1982. It has since steadily declined to 11.7% today.

If past trends are an indicator of future trends, this number is set to continue to diminish. While this is true of the general global trend, in a context of low growth in other sectors, it spells worsening economic prospects for South Africa.

Historians tell us that even at its height, South Africa’s manufacturing was manufacturing only by the strictest definition. Looked at this way, the country’s reputation for past manufacturing prowess is due for reconsideration. In his widely acclaimed 2005 book, Season of Hope, economist Alan Hirsch notes that our manufacturing firms never had a reputation for innovation.

He highlights that a large part of South Africa’s “manufactured” products are basic metals such as iron, steel and aluminium, as well as basic chemicals, wood pulp and paper that represent manufacturing only in the narrowest sense according to international classifications. The processes rather entail final stages in the extraction of minerals than preparatory beneficiation.

South Africa relies more on the advantage afforded by its climate and abundance of natural resources than on acquired skills or expertise. Nor were engineers known for their ability to innovate products and processes. As a result, South African manufacturers were mostly under creative licence to intellectual property (IP) holders domiciled in the industrialised world. Policy was at the root of this; the protectionist government encouraged copying for the domestic market instead of innovating at a world-class level.

Ben Fine and other economists also note that the country’s industrialisation and infrastructure roll-out were always to the benefit and service of exporting primary resources. They term this the “minerals-energy complex”. South Africa’s military production had potential, but it never attained a sufficient international market due to global abhorrence of its political system. That system also stood in the way of a whole-of-society approach to industrialisation.

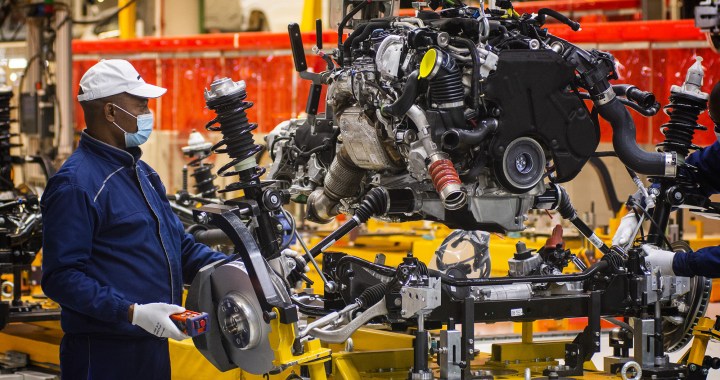

In present terms, reports paint a bleak picture. Noticeably, as recently as 2019, Statistics South Africa noted that the top sources of employment in the manufacturing sector were basic metals, fabricated products and machinery equipment (22% of the industry). These were followed by food, beverages and tobacco (20%), which are also classified as manufactured products. Wood and wood products followed at 11.29%. Advanced and semi-advanced manufacturing constituted slightly more than 11% of the industry, with motor vehicles (including parts and accessories) at 7%, followed by electrical machinery and communications and professional equipment at 2% each.

Between 2010 and 2020, imports as a percentage of domestic manufacturing sales have hovered above 59.86% and peaked at 70.47% in 2013. This shows a growing consumption of technology without a domestic market to reap the benefits and create employment.

In understanding why contemporary South Africa has not been actively industrialising, four key factors have to be understood. The first is technical. Quite simply, the country has an inadequate number of engineers to meet its industrialisation needs.

According to the Engineering Council of South Africa, the country is substantially behind the global standard for the number of engineers per population. We have one engineer per 2,600 people whereas leading countries have one engineer serving 40 people. There have also been many engineers either not active in their industries of training (instead of working in banks or as consultants) or leaving the country altogether.

This brain drain could perhaps be given a positive spin and, for example, be used for internationalisation and ensuring South Africa attains world-class competitiveness. But this has not been the case due to the three additional factors hindering South African industrialisation, which are related to policy.

First, South Africa does not have economies of scale. Notably, it has a limited market size, with a small total population and an even more limited number of consumers who can afford to consume locally made industrial goods. This makes investors sceptical about entering the market. For example, the Joule electric car was launched in 2008 to much fanfare, but was discontinued by 2012. Several reasons have been put forth to explain its failure, including that it was ahead of its time, or that it was too expensive to produce at a commercially viable price (even with government subsidies).

We may add the need for a robust and seamless IP regime that caters for the efficient registration of patents with commercial potential. Moreover, the country is yet to recover from the effects of the divestment campaign of the 1980s, which saw domestic financiers leave the country in droves in search of greener pastures under the late apartheid regime and early democratic era.

But all these reasons are underscored by one common truth: the Joule, which was entirely South African made, failed because South Africa did not have economies of scale. Had it been introduced in India, it would have had a higher chance of success. To be sure, countries similar in size to South Africa or even smaller (such as South Korea and Taiwan) have been leaders in industrialisation, owing to global links and producing for global consumption. South Africa’s award-winning, world-class port infrastructure seems to be used mainly for importing foreign products rather than exporting South African-made goods.

Third, South Africa has not invested in advanced production methods (systems of manufacturing). Indeed, the country has been de-industrialising consistently over the past several decades. While the rest of the world has found new ways to increase production efficiency, South Africa’s factories have been involved in light manufacturing or acting as assembly points. This speaks to the lack of a coherent manufacturing strategy that would seek to leverage the government’s various levels, departments and enterprises towards this policy.

In the 2020 State of the Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa reiterated that the government’s vision for industrialisation is underpinned by sector master plans meant to rejuvenate and grow critical industries. Only four of these plans have been put into action so far.

A justified criticism of these, however, has been that they consist of more agricultural output (such as poultry and sugar) than manufacturing, while the manufacture of advanced products such as automobiles mainly draws from foreign vehicles – Ford, Toyota, Nissan, Mercedes-Benz and Isuzu – with no articulated plan for graduating towards locally made ones. To be sure, agriculture can serve as a basis for industrialisation, and many industrialised countries continue to rely on agriculture as a major area of economic activity. New Zealand and the Netherlands are perhaps the leading examples of this. But it is not clear whether that is what is being pursued by the South African government.

Finally, the country has seen little in the way of venture capital. This is an outcome of the previous three factors; financiers are incentivised to invest their capital when they see a skilled local talent pool, economies of scale and global links as well as policy coherence.

We may add the need for a robust and seamless IP regime that caters for the efficient registration of patents with commercial potential. Moreover, the country is yet to recover from the effects of the divestment campaign of the 1980s, which saw domestic financiers leave the country in droves in search of greener pastures under the late apartheid regime and early democratic era.

It is critical for South Africa to attain industrialisation; for the purposes of recovery after Covid-19 and for resolving the country’s problems of (mostly youth) unemployment, poverty and inequality. In doing so, it cannot achieve a turnaround without responding to these four problems.

The realities of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) will also mean that the country has to take advantage of the transformation under way while mitigating its negatives. This could take the form of using artificial intelligence (AI) and big data to identify domestic and international markets and their patterns of consumption to inform and drive industrial output. These will help achieve scale and cost-effectiveness.

These insights can, in turn, be used in producing graduates who have market relevance while training them to work within the new manufacturing paradigm of the 4IR, particularly the smart factory, which is based on the Internet of Things. The country’s master plans need to reflect these factors if South Africa is finally to achieve its elusive quest for sustained industrialisation. DM

Dr Bhaso Ndzendze and Professor Tshilidzi Marwala, both from the University of Johannesburg, are authors of the forthcoming book Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technologies in International Relations (World Scientific Press). Reach them on Twitter: @NdzendzeBhaso and @txm1971

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.