OP-ED

Renaming cities: Let’s promote the Eastern Cape’s rich, hidden history of endorsing the pen over the sword

The news that the former settler cities of East London and Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape were getting new names sparked an outcry from the DA and a few local residents, but it was celebrated and welcomed by others. In the public debate, much more attention focused on the pronunciation of the new names than on their complex meanings and histories.

Is the decision to rename the airport at East London after King Phalo appropriate? Why was Chief Phato of the amaGqunukhwebe nation, who had his Great Place near the site of the modern airport, not chosen instead? And, what does the proposed name for the city itself, Ku Gompo, actually mean or represent, and how does it relate to the city and its people?

The absence of reference to the amaGqunukhwebe nation under the leadership of Chief Phato, who occupied the coastal plains between the Keiskamma and Kei rivers for the entire 19th century, is rather surprising. In its place, the emphasis has been placed on King Phalo, the 18th-century founding father of the pure Xhosa nation, which subsequently split due to the conflicts between warring sons.

Is the renaming process to reconstitute the Xhosa nation, deliberately erasing and silencing complex histories within the city region and those of the hybrid groups like the Gqunukhwebe people, who often chose negotiation and diplomacy over war, and are regarded as a mixed nation of war refugees, diverse Khoi chieftains and Xhosa clans?

Are these insensitivities in any way comparable to those employed by the arch-colonialist Sir Harry Smith, when he originally named East London back in 1847? And, is it a bad thing to acknowledge complexity and hybridity, and to break from popular histories of ethnic nationalism?

Ku Gompo and Sir Harry Smith

The news that the former settler cities of East London and Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape were getting new names sparked an outcry from the DA and a few local residents, but it was celebrated and welcomed by others. In the public debate, much more attention focused on the pronunciation of the new names than on their meanings and histories.

The fact that they were Xhosa names, not English ones, attracted more attention than what they meant. So, what exactly does Ku Gompo reference in the case of East London? It is the Xhosa name for the place known as Cove Rock near East London, which is a site of religious significance for the Xhosa people as it is where the great Xhosa ancestral spirits, abantu bomlambo, are believed to reside in the water beneath the rock. The term ‘Gompo’ refers to the roaring sound that comes from the sea beneath the rock and shakes the earth.

During the frontier wars of the 19th century, Xhosa healers, warriors and prophets visited the Gompo site, seeking spiritual strength, upliftment and inspiration to fight the British colonial forces and reclaim their land. The most famous visitor to the site in the 19th century was the Xhosa prophet and war chief Nxele Makhanda, who brought his followers to Gompo in 1817, where he prophesied that they would see the ancestors and their cattle rise from the sea and follow them into battle to vanquish and remove the settlers from the land.

Four decades later, in the 1850s, a young Xhosa prophetess Nongqawuse articulated a similar vision of the future at a place east of the Kei River, where the descendants of the royal House of Phalo lived and the great Xhosa King Hintsa had been murdered by the colonialists. She urged the Xhosa to kill their cattle across the region so that “new people” with cattle could rise from the river mouths and drive the white people into the sea, restoring peace and harmony to the Xhosa nation.

In frontier history, Gompo emerged as a symbol and source of power and resistance to the colonial regime. It is a place where the ancestors of the Xhosa people could be reached to bring unity and resolve to the leaders of the nation. The name and place invoke a sense of cultural unity, purity and possession, but ignore the fact that the coastal belt between the Fish and the Kei rivers was home to a hybrid amalgam of people from Khoi, Mfengu (refugee) and Xhosa clans, who were negotiators rather than warriors.

In finding and implanting pure Xhosa warrior histories of the city, the naming committee is denying the region its own history. This is not dissimilar to what the British colonial governor Sir Smith did when he named the small port settlement on the Buffalo River East London. He sought to impose a British imperial imprint on the place, pretending that local people, like the Gqunukhwebe, did not exist and would be of little historical consequence, except as servants to the white people.

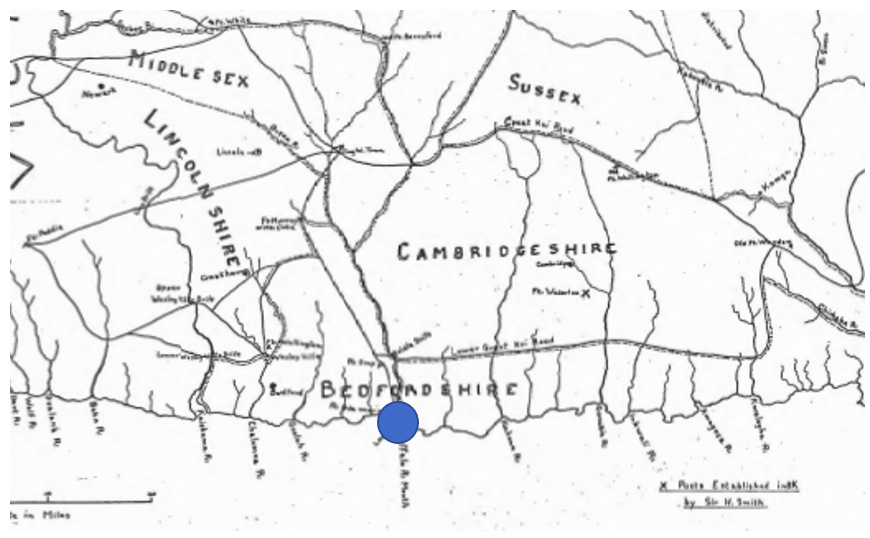

In Smith’s imagination, the new settler town would blossom and become the “London” of the east, surrounded by thriving new agrarian settler counties with names like Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire and Northumberland. It was an imagination of unbridled colonial ambition and audacity, an act of cultural arrogance and the denial of history.

Sir Harry Smith’s Sketchbook in 1849 imagining the countryside around East London.

But what of Chief Phato and his Gqunukhwebe people? Where did they come from? How did they get to Buffalo City and how might their history matter today? And why should the naming committee embrace their complexity and hybridity as a people, rather than dispense with them in favour of more glorious notions of cultural purity?

The hidden history of the Gqunukhwebe

In the 19th century, the Gqunukhwebe polity was made up of fragments of old Khoi chieftaincies and Xhosa clans who lived in and around the territory known today as Buffalo City. The nation was forged under the reign of King Tshiwo (1670-1702) of the amaXhosa, who pulled together smaller Khoi chieftaincies of the Gonaqua, Hoenheniqua, Inqua and others into the amaGqunukhwebe nation that later incorporated Mfengu refugees too.

Colonial maps from the early 19th century suggest that Buffalo River, on which East London is located, was a dividing line between the amaGqunukhwebe to the west and the amaNdlambe people to the east. However, by the mid-19th century, the Gqunukhwebe had moved beyond the Buffalo River and the Ndlambe had shifted further east, closer to the Kei River. Thus, when East London was created as a port town in 1847, Gqunukhwebe kraals were spotted around the river mouth and on the land that was later to become the white suburbs of the city.

The land was thus not vacant, as the British liked to allege, but occupied and used by indigenous inhabitants before the British reached an agreement with Phato to use the land between the Buffalo and Nahoon rivers in exchange for African independence outside the town. After this, the focus for the new town’s development moved away from the original West Bank settlement and fortifications at the river mouth to the land to the east, which was used for suburban allotments and small-scale farm allotments.

The modern history of the Gqunukhwebe is associated with the reign of Paramount Chief Phato, who lived to the west of Buffalo River and led the nation in the 19th century. Phato and his brothers, Kobe and Kama, moved across the Keiskamma River from the Zuurvelt as they lost land to settlers.

Phato’s ancestors had been occupying the coastal belt between Port Elizabeth and Port Alfred for at least 100 years before the arrival of large groups of British colonists settled in the area by the government in London and the Cape Colony. The nation was pushed eastwards with the conquest of the Zuurvelt and the eastward movement of the British colonial frontier. The amaNdlambe nation was pushed further eastwards as the Gqunukhwebe were pushed back towards and beyond the Buffalo River.

John Brownlee’s 1822 map of the coastal plain before the amaNdlambe moved east.

In the early 19th century, Chief Phato had set up his Great Place to the west of Buffalo River near Kidd’s Beach, inside the current municipal boundaries of Buffalo City. The chieftains of his brothers, Kobe and Kama, lay further west in the so-called ceded territory – the buffer strip created by the British on the frontier in the 1820s.

Even though his Great Place lay beyond the colonial frontier at this time, Phato felt that it would be wise for him to invite white missionaries to work among his people, so that they would be better equipped to negotiate with the invading British colonists and their settler regime. This paved the way for the arrival of Wesleyan missionary, Reverend William Shaw, who built a mission station and church adjacent to Phato’s Great Place, and another in Gqunukhwebe territory near Mount Coke and the colonial military outpost of Fort Murray, also in the current municipal boundaries of Buffalo City.

The presence and influence of Shaw and his followers among the Gqunukhwebe meant that there was no attempt to expropriate Phato’s land before the end of the 19th century. It was only after the re-annexation of British Kaffraria in 1866 that the threat of expropriation of land along the coast started to threaten Gqunukhwebe sovereignty and settlement. The coastal belt between Buffalo River and King William’s Town was not a settler farming zone at that stage. It was nevertheless strategic because of the transit of goods, troops and arms from the river mouth to King William’s Town, which stood on the frontier in the Amathole Basin.

While Phato held his own in this space, a key political turning point came in the 1840s before the War of the Axe of 1846-47, when his brother, Kama, turned down the hand in marriage of a Ndlambe princess, who would have become his second wife. Kama refused the offer of marriage on the grounds that he was now a devout Christian who rejected the Xhosa tradition of polygamy. This shamed Phato. He was not a Christian and he disowned his brother, Kama, to hold on to his alliance with the Ndlambe. His brother then left the coastal plains for colonial protection at Middledrift, beyond King William’s Town.

In the literature, Kama is recognised as the first fully Christianised Xhosa chief on the frontier. This meant that Kama was now favoured by the colonialists over his “pagan brother”. Phato was also criticised by his own people for allowing the nation to split as a result of colonial intervention. Growing internal divisions sharpened at the time of the Xhosa Cattle Killing of 1856-57, when many of Phato’s followers fell under the influence of the Ndlambe prophetess and “believer” Nkosi.

Many Gqunukhwebe joined the Ndlambe in killing their cattle and destroying their crops. The devastation that the cattle-killing wrought in British Kaffraria as a whole was extraordinary as the population of the region declined from more than 100,000 to 37,000 between January and December 1857. The power of Phato was crushed and the colonists now seized land and forced poor, starving Gqunukhwebe and Ndlambe into wage labour on public works such as the colonial railways, or on the farms that had been newly created by white landowners.

These conditions made it possible for the British to invite German settlers to open up the coastal plains with new farms and towns, such as Berlin and Stutterheim. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Phato was arrested by the colonial government on trumped-up charges and sent to Robben Island, where he joined other Xhosa chiefs, including Maqoma, in jail. It was also at this time that his chieftaincy on the coastal belt around Buffalo City was divided among settler farmers and mission stations, leaving only small pockets of African-owned land.

Hybrid histories and the modern city

What I find fascinating about Chief Phato was that he rejected colonial acculturation, liberalism and the temptation of war in his efforts to defend the culture, livelihood and the rights of his people. He accommodated the missionaries, even inviting Reverend Shaw to settle close to his Great Place, but not for the sake of conversion, as happened to his Christianised brother Kama, but for the purpose of observation, protection and diplomacy. His followers were a diverse but proud nation that absorbed strangers and accommodated the traditions and outlooks of others, combining Khoi and Xhosa traditions and beliefs, with the new Christian visions of the Wesleyans and the Mfengu people.

Chief Phato remained the dominant African political figure on the coastal plains from the 1820s through to the 1880s. He was a shrewd, principled Africanist who chose the way of the pen rather than the sword in most of his dealings with the colonial government. He was a negotiator and avid protector of sovereignty and self-determination, and used the colonial idea of a “confederacy of chieftaincies” on the frontier to hold on to the land and independence of his people. In the 1850s, he also did not fall under the spell of the Ndlambe prophetess Nkosi, an ally of Nongqawuse, and the madness of the Xhosa chieftains across the Kei River.

There is something in Phato’s acumen, determined Africanism, and his pursuit and imagination of building a hybrid nation of many talents and traditions that might be of greater service to the struggling city of East London and its people than a symbolic return to the heroic image of a pure, do-or-die Xhosa warrior nation, staring at their foes across the scorched earth. Phato and his people, despite all their complexities and lack of purity, are potentially a great source of hope in the current world. They may be seen as breaking the deadlock between liberalism and Africanism by rejecting easy oppositions and the need for essentialism and African purity.

It is an image of the city, which its peaceful liberation icon Steve Bantu Biko, whose statue stands in front of City Hall, would probably have strongly endorsed. DM

Professor Leslie Bank is a Deputy Executive Director at the Human Sciences Research Council in Cape Town and author of a recent book on East London, City of Broken Dreams: Myth-making, Nationalism and Universities in a South African Motor City (HSRC and Michigan State University Press, 2019).

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

How do you market and sell something that no one can pronounce?

Most informative and interesting factual and opinion piece.