OP-ED

Reflections of a Wayward Boy: Stateless (and hatless) in Tangier

I once had a brief experience of what it is like to be a ‘stateless person’ — someone granted asylum or given some sort of permission to stay in a country of exile without the right to reside anywhere else. I’ll never forget it, but my exile, including the period of being stateless, meant I was still able to travel, and my experience was one of relative ease, comfort and enlightenment of a sort. The world today, especially for millions of stateless men, women and children, is vastly different.

Fewer than four months after arriving in London clutching a slip of paper signed by the British high commissioner in Lusaka granting me entry to Britain, I got a job, was admitted to university, and, along with several other exiles, landed a handsome United Nations fellowship. This provided for a decent enough living and also paid the tuition fees.

However, I was effectively stateless and therefore without a passport and unable to travel freely. Other exiles were in a similar position and some, like me, had to settle for a Home Office folder. It contained personal details, photo affixed, and noted, in my case that nationality was “South African N/D” (not determined). I needed a visa for any country to or through which I wished to travel. This meant long waits at embassies and border posts, paying for visas and being delayed and asked the same questions by inevitably unfriendly officials at all points. Not a pleasant experience as I travelled with my then soon-to-be wife, Barbara Edmunds, to and from Morocco for the December university break in 1966.

But that journey — and Morocco itself — was an eye opener. Quite apart from the fact that Barbara sailed through borders without problems, although she carried a South African passport that was strangely restricted to just one year. But the importance of a passport was only one minor lesson: that once-notorious “international city”, Tangier, provided many more.

We arrived very short of money because Barbara had lost her wallet somewhere in France on the way down. But the Hotel Chauen in the centre of the medina — the “Arab quarter” of the city — was remarkably inexpensive. As such, it had become a major stop-off point on the hippie “pot” trail that extended from Marrakech in the west to Kabul in Afghanistan and even further east.

The Chauen was hosted by a large Berber woman who seemed to be perpetually happy and who spent the best part of each day sitting in the central courtyard of the two-storey building with its additional, single, rooftop room. She spoke no English, very little French, but could make instant — and accurate — calculations of various currencies into Moroccan dirhams. And the rate per person to stay in one of her rooms did not vary.

We got to know more about her and the other guests because we stayed for two weeks while most of the more recent — foreign — arrivals usually only stayed for no more than two or three days. This foreign influx, many of them young Americans fleeing conscription to Vietnam, ensured that the Chauen was usually quite fully booked throughout the year.

But it remained one of the traditional stopovers for travelling Moroccan salespeople such as Mahmoud who sold, on camelback, Primus stoves and prickers to residents in the southern deserts. I met and communicated with Mahmoud in my fractured French, accompanied by much mime, discovering that he spent a week or two every year at the Chauen. He invited Barbara and me to a dinner in his room which he cooked on a paraffin-powered Primus stove and in a single pot, both brought out, along with packets of spices, from his battered suitcase. It was a culinary and organisational display par excellence.

However, because, after a few days, we had become the somewhat established residents, many of the foreign travellers tended to gather in our room in the evenings, bringing bottles of cheap Moroccan wine bought in the Quartier Francais (colonial French Quarter) and with hash pipes and pouches of local dagga (cannabis) and hashish to hand. Conversations — never political debates — went on into the night. In the mornings, Barbara and I would collect the empty bottles and claim the deposits which usually covered the cost of our accommodation for the next night.

Because of the nightly windfall of empties, we did not have to dip into what was left of our money and could stay on. It made an indelible impression that the empties had been discarded without any thought about their value; that no thought had even been given to what might happen to this detritus from one boozy night that happened to fund us. And this was reinforced by noticing a couple of barefoot American draft dodgers begging on the streets of the medina, relying on the Muslim obligation of Zakat (charitable giving) to tide them over until the next cheque arrived via American Express.

For much of the background on the barefoot, begging hippies I relied on Alex, the secretive, hardly ever seen and long-term resident of the single rooftop room at the Chauen. It intrigued me that a foreigner should live so secluded a life: I made a point of making contact. As it turned out, Alex too was dodging being drafted into the military, but he had set up a business in his eyrie: exporting small souvenir Moroccan leather camels to the US. Except that some camels, sent to specific addresses, contained, inside them, quantities of hashish wrapped in tinfoil.

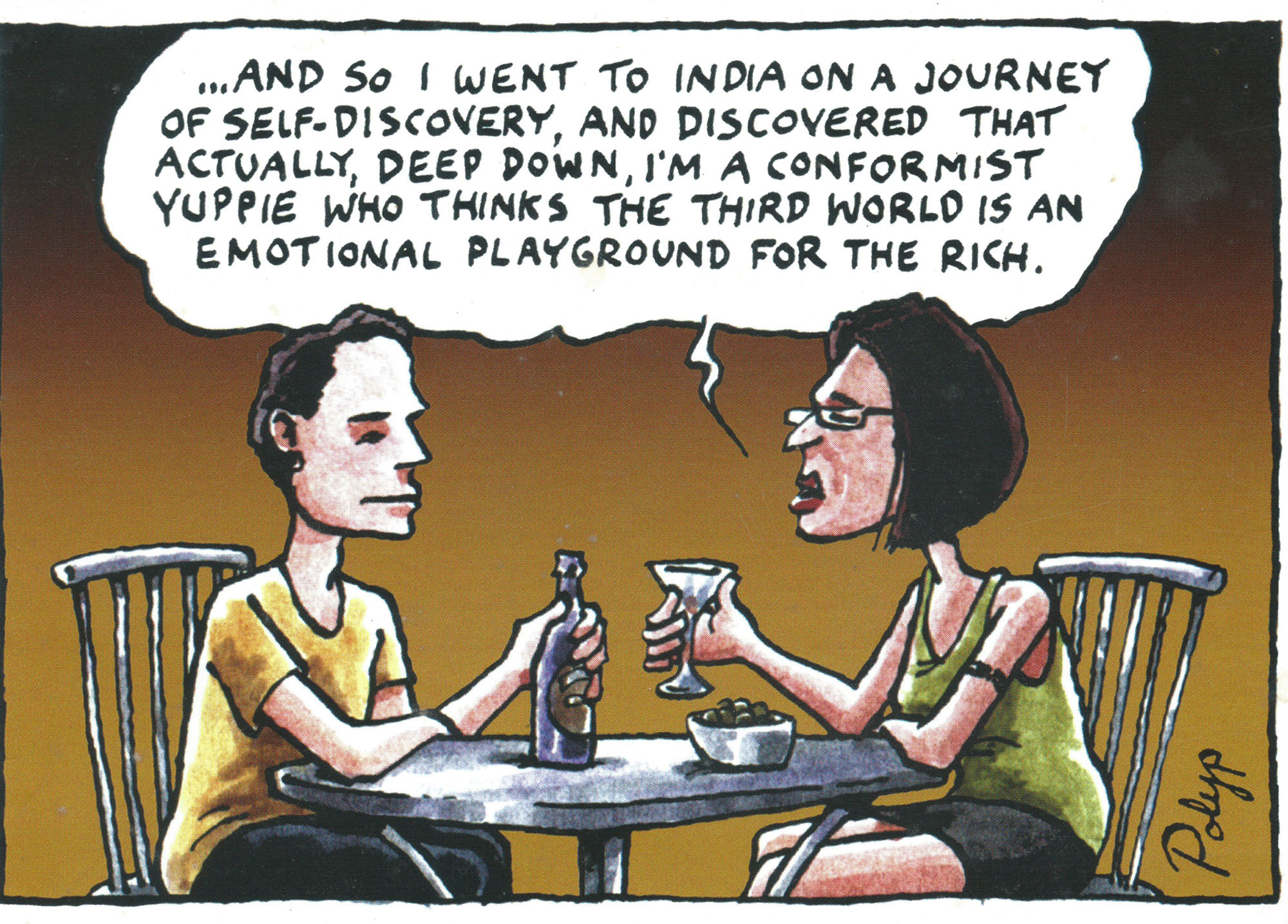

Many years later, after I had spoken to a good friend about these experiences, he sent me a postcard that summed up much of what we had experienced.

My personal aversion to the use of cannabis and hashish (not shared by Barbara) was strengthened since getting high seemed to provide an escape not only from reality, but from trying to do anything about changing it. But there were some very animated conversations in our often crowded, smoke-filled room where my cherished bush hat had pride of place, hanging from a bed post. One young Canadian, Murphy, became obsessed with the hat and offered to buy it, eventually offering $15. Barbara remembers me flatly rejecting this substantial offer, declaring grandly: “I travel nowhere without it.”

At the time the discussion was about travelling, by kayak or open canoe. It was triggered by a newspaper item I had seen about two Inuit (Eskimo) fishermen from Greenland who had been blown off course and ended up in Scotland. At some stage I maintained that kayaks were so stable, I could paddle one from London to Tangier. Another Canadian, Kent Warmington, who was later to become a lifelong friend, bet me I couldn’t do any such thing.

And there the whole matter might have ended, with the bet and even much of the conversation forgotten. But in the morning my hat was gone. Murphy had stolen it — and was heading for Spain on the morning ferry. Kent, Barbara and I raced to the harbour in time to see the ferry sailing out with Murphy and my hat on board. “Never mind,” said Kent. “I’ll get your hat back.”

It was a good, friendly gesture that Barbara and I didn’t take seriously. But when we left to return to London a few days later, Barbara gave Kent her London address: he should contact us if ever he came to Britain. Neither of us thought there was much chance of ever seeing him — let alone the hat — again.

We certainly didn’t spend any time thinking about it as we were pitched into one of the most hectic political times of our lives. Barbara for a brief spell also became stateless when the government refused to renew her passport, but by then we were married and had both become citizens of the Republic of Ireland. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.