DAILY MAVERICK WEBINAR

Frederik van Zyl Slabbert: A man of his time, still missed in ours

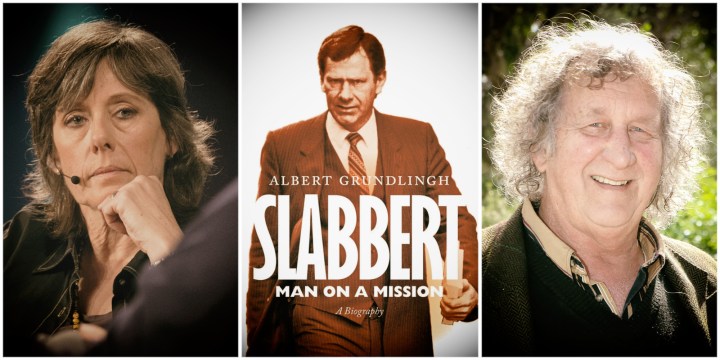

The level of interest in a new biography of Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, written by Stellenbosch historian Albert Grundlingh, is an indication of the man’s mystique. More than a decade after Slabbert’s death, his work and legacy continue to be pored over — including by Grundlingh and Marianne Thamm in a Daily Maverick webinar this week.

Former South African opposition leader Frederik van Zyl Slabbert is gone but not forgotten — and a new biography by Albert Grundlingh is reinvigorating interest in the maverick politician.

Described by Daily Maverick’s Marianne Thamm in a webinar this week as “one of the most intriguing figures” in the history of South African politics, Slabbert is perhaps best known today for his meeting the ANC in exile in 1987. But, as Grundlingh — author of Slabbert: Man on a Mission — made clear, this was just one event in a life filled with significance.

Grundlingh told the webinar that Slabbert occupied an “insider/outsider” space from a young age. A religious Afrikaans boy who was a very good rugby player, Slabbert was gripped from an early age by a sense of not quite belonging.

Arriving at the University of Stellenbosch to study in the early 1960s, Slabbert was no normal middle-class white student, Grundlingh said.

“He came there as an old soul,” the historian said: Slabbert had already worked for a period in Johannesburg; had participated in a communist discussion group, and had listened to the ideas of PAC-founder Robert Sobukwe.

An important event on the road to opening Slabbert’s eyes to the nature of apartheid happened when the student went to do missionary work in the Cape Town township of Langa shortly after the Sharpeville Massacre. Slabbert and others were chased away. This led him to start seriously considering the roots of this antagonism and the rationality of apartheid laws, Grundlingh said.

Perhaps the major catalyst for Slabbert’s political awakening, Grundlingh suggested, occurred in response to a claim by apartheid cabinet minister Piet Koornhof that “everybody was happy in Soweto”.

Slabbert, bent on rational approaches to issues and empirical observation, went to Soweto and asked residents whether this was the case.

“Residents were enraged,” said Grundlingh: Slabbert was lucky to get out without violence. It was a turning point for him.

It demonstrated to Slabbert, said Grundlingh, that “what government thinks and what is happening on the ground are worlds apart”.

Slabbert, already making a name for himself as a charismatic Afrikaner intellectual, had completed his doctorate at Stellenbosch by the time the United Party asked him to stand as an electoral candidate. But the Progressive Federal Party’s Colin Eglin managed to convince Slabbert that the PFP was the party he was most suited to represent, in Rondebosch.

“He was sick and tired of being an ‘academic housekeeper’ and ready for a new challenge,” said Grundlingh.

And so Slabbert’s political career officially began, as an MP for the DA-precursor that was the PFP, alongside the party’s most famous parliamentarian Helen Suzman.

But Slabbert quickly realised that Parliament was anti-intellectual and boring — something he worked to change.

“He changed the grammar of Parliament, and that wasn’t sufficiently recognised at the time,” Grundlingh said.

“He got them to talk about things like the possibility of a new constitution.”

Slabbert, a young Afrikaner questioning the establishment in this manner, quickly became an object of fascination and admiration to the English-speaking media. Grundlingh joked that a prevailing sentiment at the time was: “If only all Afrikaners could be like Slabbert.”

In fact, despite Slabbert’s ability to win over white English-speaking South Africans, he maintained a cautious relationship with white liberalism in the country — rejecting the “haughty sneer” that he saw as part and parcel of the ideology.

After 12 years as a parliamentarian, Slabbert resigned in 1986. His departure caused “quite a furore”, said Grundlingh, and evoked bitterness in some quarters that remains to this day. Helen Suzman was one of those infuriated by Slabbert’s departure, which she felt was selfish. Grundlingh says the two only made peace later in life.

Explaining Slabbert’s decision to leave the National Assembly, Grundlingh said: “What got to him was that there was no change he could identify happening through Parliament.” He was also tired of being used as the liberal who could be paraded to give a veneer of respectability to government decisions.

Grundlingh believes that Slabbert had “no formal plan” for what he would do after leaving Parliament. Almost immediately, however, the politician began working on ways of opening up channels of communication with the ANC.

It was Slabbert who famously succeeded in doing the counter-intuitive: bringing together Afrikaners and ANC leaders in Dakar in 1986. In this, as in so many other ways in his life, Slabbert broke the logjam.

Grundlingh said that Slabbert and Thabo Mbeki got on particularly well, but after Mbeki entered government the distance grew between them.

After the transition, Mbeki had no further use for Slabbert, who had no formal constituency to offer him. Grundlingh says Slabbert also had misgivings about president Nelson Mandela, who he saw as “good on the PR front” but less good at the “nuts and bolts of running a country”.

Slabbert “would not easily have become a compliant ANC member”, Grundlingh said, adding that it was “impossible to think that he would have served in the same cabinet as Mbeki” in the context of Mbeki’s Aids conspiracy theories.

Suzman had warned Slabbert against the ANC in the early 1990s, saying: “You will be disappointed.”

Already from encountering ANC leaders in exile, Slabbert had an “inkling” that there was “a lack of accountability as far as finances were concerned”, Grundlingh said.

“It was far too easy to pummel Nordic countries’ consciences for money without being held accountable.”

But the extent of ANC corruption today, the historian suggested, would be well beyond Slabbert’s imagination. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

During the lead-up to the vote on the tri-cameral parliament, I was travelling from Kokstad to Pietermaritzburg with Frederik van Zyl Slabbert and James Rennie (I was his farm manager at the time), to help with the “no vote” campaign. I was despatched to attend a rally with Piet Koornhof, as I was a recently-baptised member of the Dutch Reformed Church, a member of the Kokstad Kerkraad and an up-and-coming young organic farmer. I tackled Koornhof on the three pillars of apartheid, which were clearly crumbling, and he was unable to answer my argument, which had been honed with the help of the two wise men. Piet Promises, we called him, was everybody’s pleasant uncle (if you were white), and a remarkable egg-dancer. What impressed me about Frederik was the clarity of his intellect and his penetrating honesty. I asked him whether he missed being in academia, and he looked dreamy for a moment, and said, “Ah yes, that last bastion of protected employment; I don’t really miss it much!” Having just retired from academia myself I can appreciate how returning to “the real world” is something of a shock, but also very refreshing! Frederik was a giant, a rare statesman in the world of politicians.