ODE TO JOY

Thoko Ndlozi & the Healjoy Sisterhood

A portrait of a defiant soul singer, and the band and the world she helped construct.

“Everyone loves you when you are dead.”

– Neil Strauss, Everyone Loves You When You Are Dead & Other Things I learned from Famous People (Candidate Books).

“I was hot, baby. I never played games on that stage.”

– Thoko Thomo aka “Shukuma Thoko,” A Common Hunger to Sing.

Thokozile Elizabeth Ndlozi has been silent for too long. But like her 1950s namesake Thoko Thomo, the speedball inferno from George Goch known for her high-octave package – she sang, acted, danced, pouted, and teased audiences and fellow collaborators with peerless brio – before being effectively “disappeared” from public memory prior to her actual death in 1995, Thoko Ndlozi, who died on 14 January at 74, just won’t die.

Not dying – as opposed to being dead and famous, or alive and unseen, unfelt, unheard and unrecognised – is a remarkable feat on its own.

We’re in a time in which artists and social actors, be they the young, dazzling and dead, or old, patronised and spooled out of prime time, are subjected to a cycle of complex erasure overwritten with the optics of celebration: “Everyone loves you when you are dead.”

“Love” is often the starting point in this vicious chain of erasure, and a key part of this now-perfected “love” of the famously dead we never really knew is momentary public reclamation.

The reclamation itself, which feels like adding your name to the graffiti-scrawled wall of professional mourners – another “Toloki” from Zakes Mda’s Ways of Dying – is characterised by decontextualised, pixelated love: A sudden visual testimonial of fans and friends raiding their phones’ memory banks for that one shot that illustrates just how close you were to the dearly, famous, departed.

Insert a weeping emoji. Click!

I have never been intimately close to Thoko Ndlozi. And yet, thanks to the passing of the once-fawned-over star who was of an age when “celebrity” meant well-deserved and rewarded, I’m drawn to her story.

Thokozile Elizabeth Ndlozi’s mother, Anna Maphori Ndlozi, never had an inkling that her best friend, the singer and revue girl Mabel Mafuya, had had a vice-grip hold over her pre-teen daughter, Thokozile, then a skinny little girl with huge dreams.

An amber-hot 1950s singer, Mafuya had teamed up with other “hot girls” of the time not named “Miriam”, “Dotty” or “Dolly”: Mary Thobei and Thandi Klaasen (née Mpambane) to form the Chord Sisters.

In 1993, “Sis May” told the authors of A Common Hunger to Sing, ZB Molefe and Mike Mzileni, that in an age when their parents were just transitioning from gold-mining settlements, trying to get a foothold in the new, multicultural “black” republics dotted around the Reef, entertainers filled the space where the heart would be longing for peace and pleasure, and the mind for security and direction.

“We looked up to Dorothy Masuka, and I need not say Dolly Rathebe was the bar against which we measured our futures, even before we started. She was everything,” she said, telling a story about growing up in Orlando in the 1950s.

“One day my friends and I were passing time, so we happened to see Dolly [Rathebe] walking down a street in Orlando East. When the great ‘Queen of the Blues’ passed our group she happened to throw away an apple she was eating. I rushed and picked up the half-eaten apple and took a good bite.”

“My mind and heart told me that if I could just bite that apple where the great Dolly had bitten, I would grow up and sing just like her, one day.”

It would not be too long before Mafuya shot the breeze with her idols, working as a session singer for Troubadour Records.

It was the heyday of girl trios, close-harmony male quartets and, occasionally, a sparkling diamond such as Masuka would cut through the cacophony of marabi, tshaba-tshaba, big band jazz and mbaqanga. She recorded a single that had township and freehold settlement dives serving a township brew, sqo, free, if last night’s “Barberton” (a mule-kick of African brew), or tsotsis, did not kill you.

It was not as romantic as monochrome and dusty sepia images of the era would love us to believe. Life for working-class black folks, and especially women, was tumultuous, burdensome, precarious and on a knife’s edge.

Often, the tension would be relieved with the edge of a blade: black life has always been rendered cheap.

It was out of this colonial condition and how black folks internalised it that Thoko Ndlozi’s idol, Mafuya, joined a slew of her peers and apple-discarding idols to rip the township air with hit after hit: Hula Hoop, Nomathemba, and the biggest of them all, a Tin Pan Alley ditty, Tickey-a-Kiss. Suddenly, girl was hot, girl was fast, girl’s sound floated above the chimneys piercing through the tuberculosis-inducing asbestos roofs.

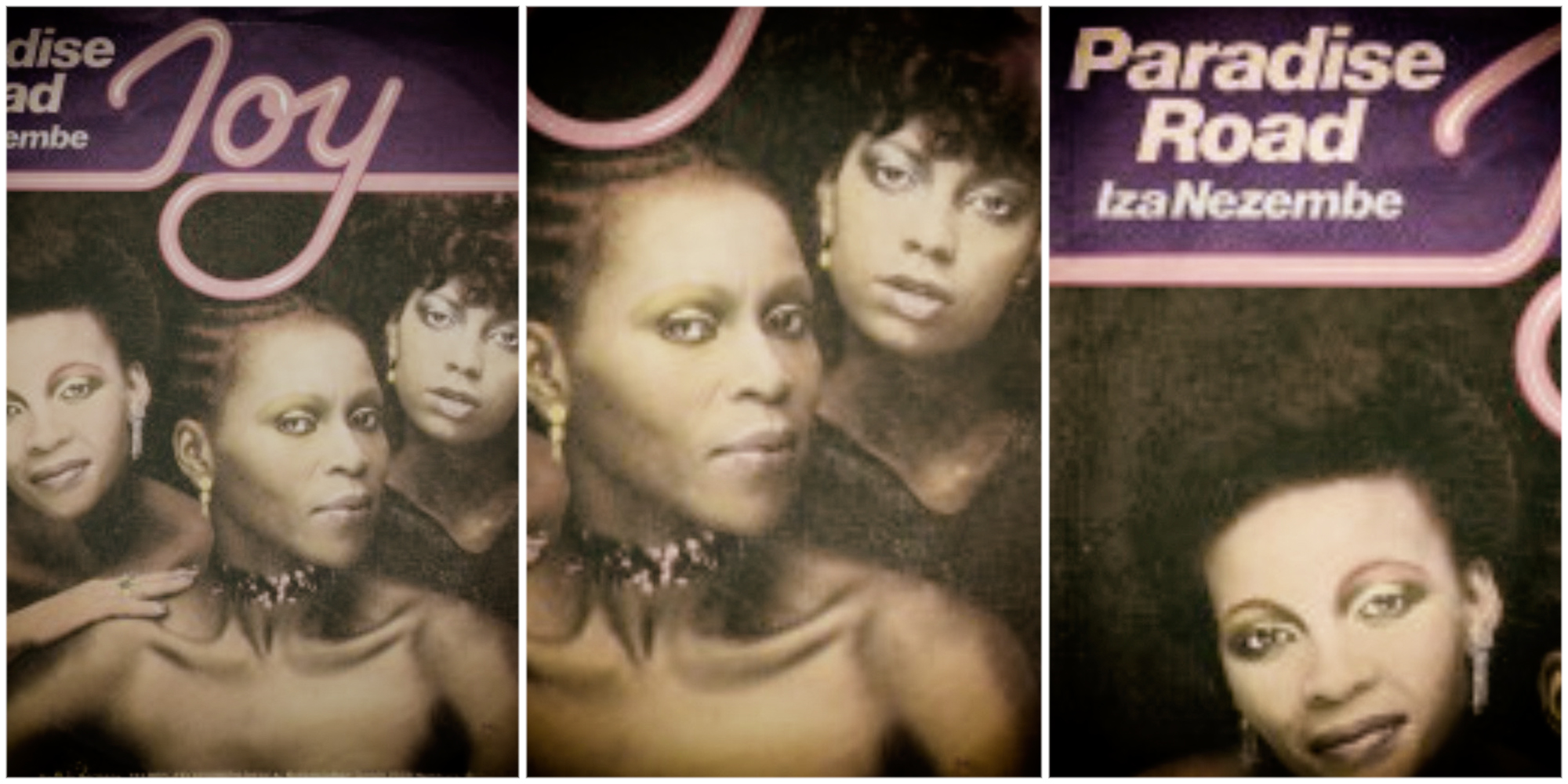

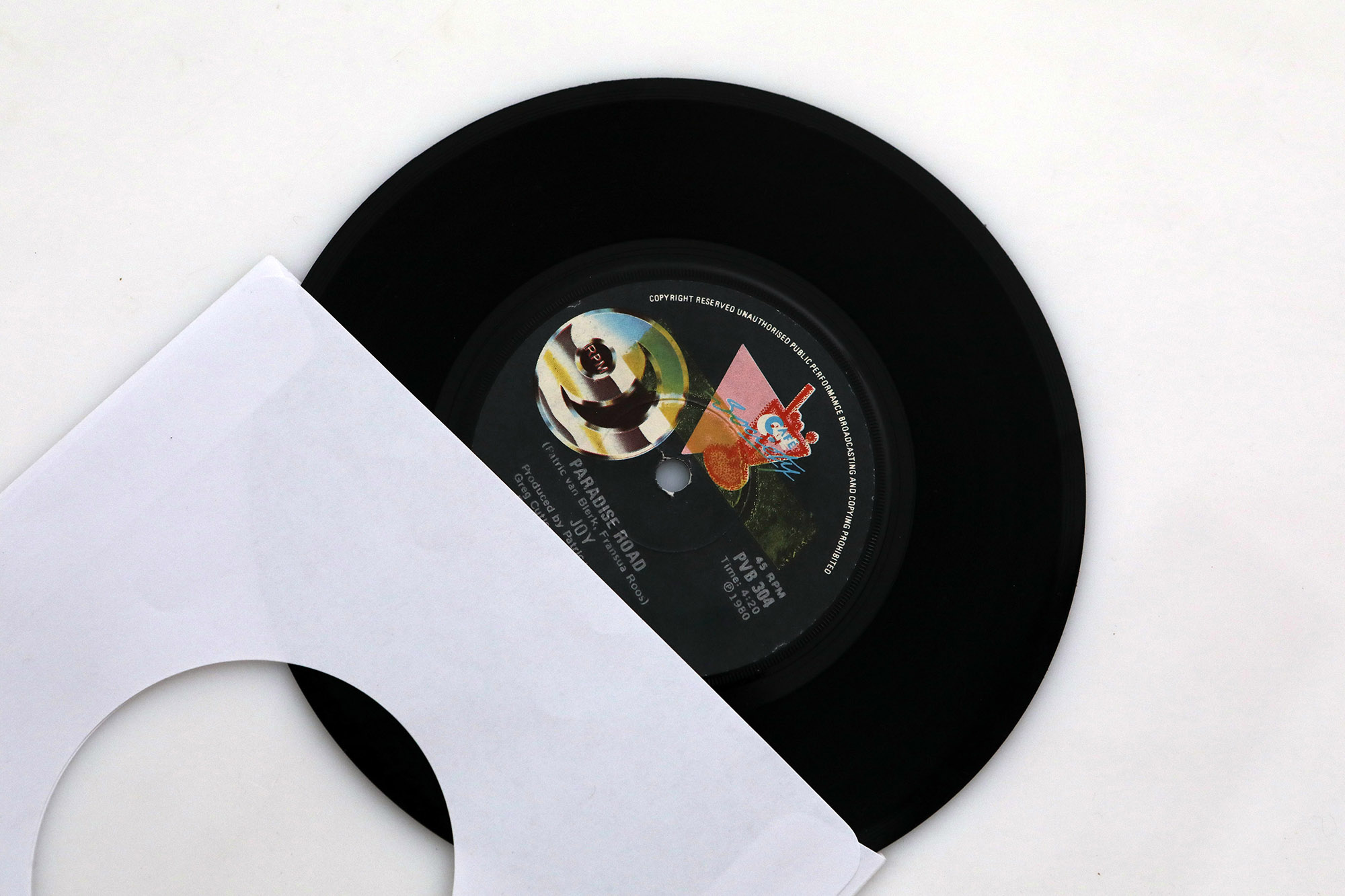

Joy’s hit Paradise Road recorded in 1980 topped the hit parade for nine weeks. (Album Cover: Discogs)

Overall, the contest for the hearts and legs of the township dwellers proved unremitting. Blues singer Emily Kwenane was out, as was Martha Mdenge with her showstoppers Mgewu Ndini and Ibhande Ngelam.

Contrary to urban historians’ and writers’ mythology that the 1950s were Miriam Makeba’s, and hers alone, evidence points to a broader black women’s pop (mbaqanga) renaissance. No two ways about it. Some of the progenitors were as young as 16.

This “swing time” and its power lit a bonfire in the ribcage of young Thokozile. Her determination to follow in the footsteps of her mother’s bestie would not be denied. Her fate was sealed. You only live once, hon.

When Thoko Ndlozi left school in 1961 she joined a touring township revue – Uncle Joe’s Rhythm Cabins – which had a brief run. Around the same time she had a bit role in a play with the ominous title Divorce, written by Oswald Msimango, directed by Simon “Mabhunu” Sabela, who would later stamp his role as a film and, most memorably, a television actor of the same persuasive heft as the great Ken Gampu, Bhingo Mbonjeni and Ndaba Mhlongo.

That too, bit the dust.

Not to be dissuaded, she, like almost everyone who mattered in the 1970s black performance arts, had a stint with Gibson Kente, featuring in Sikalo and Zwi, among others.

However, Kente’s gruelling schedule and exaggerated performance technique – part passion and part African burlesque – did not seem to go well with Ndlozi’s smoother, well-comported demeanour and her love for salon jazz and balladry.

Sometime in the mid-1970s she was offered a year’s slot at Soweto’s Pelican Club, Lucky Michaels’ upscale dive in Orlando, which happened to be a launching pad for some of the young, gifted and black talents of the time.

Artists such as Thembi Mtshali, Marah Louw, 14-year-old Lebo M, and Ndlozi’s future colleague in Joy, Felicia Marion, were among those who cooed there with the silkiest of voices.

The Pelican – whose building still stands – was the Savoy and the Cotton Club, with a dash of Studio 54 thrown in for riotous measure.

But Thoko, who by this point was firmly on the cabaret circuit and also doubling up appearances at a new joint called Lovers Fantasy in Johannesburg’s inner city, was ready for the big league.

One of her closest friends, the singer Beulah Hashe, told me a week after Ndlozi’s death that, “Thoko was disciplined, a classy lass. The cabaret circuit, as she confided in me herself, suited her low-voltage demeanour and work ethic. That circuit definitely prepared her for what came next, the stuff entertainment dreams are made of.

“There was just something both reticent, yet powerful about her.

“Thoko was driven by a highly controlled, calm and yet burning ambition.”

Chorus

April 1977

Ten months after parts of Soweto and other townships around the republic went up in smoke, the soul music trio Joy emerged.

The youth were gatvol. South Africa’s townships, taking their cue from the smouldering rage and passive protests, and pressed by fear and the inevitable pressure of the police, burst into raptures of uprisings.

Urban black South Africa had been pushed to the brink by the national government and its local black proxies’ cold disregard for the dignity, and future well-being of all Africans. Its bitter contempt for authority was amplified by Soweto’s high school pupils’ temerity to confront an already set pattern of social death.

The months leading to the rapture were marked by a visible unravelling of the seams that had barely held together an ever-more threadbare social pact of black servitude and silence the youth felt they could not abide by.

Stakes couldn’t have been higher.

On 16 June 1976, as if by symbolic deed, the police helped strike the match that lit the bonfire we now casually regard as the revolution.

But sometimes the most revolutionary act an artist and entertainer can do is to put bread on their family’s table. It may not have been a total coincidence, then, that Joy was formed in the wake of an uprising.

Joy was a perfect 1970s concept. Joy was contemporary. Joy was electrifying. In retrospect you’ll be forgiven for, wickedly, mapping them out as the Atlantic African ancestors of Destiny’s Child.

Around the same time the trio was assembled, Winnie Mandela was banished from Soweto to Brandfort in the Free State. Several months later, Steve Biko would be dead.

Around the time Biko’s death rocked the souls of black folks, leaving the minister of police, in his truly insensitive hypocrisy, “cold”, a few musical outfits under the promoter Ian Bernhardt’s stable went on tour.

Billed as “Sounds Black Tour”, and led by Spirits Rejoice, featuring some of the most dynamic players of that and any other era – Gilbert Matthews, Bheki Mseleku and Duke Makasi – joined by a Cape Flats sensation, Sammy Brown, and a freshly assembled all-girl trio, some of whom had previously played cameo roles in and out of Spirits Rejoice, the university/college tour was a success.

This success was owed in no small part to the girl band featuring Anneline Malebo, Felicia Marion and Thoko Ndlozi. It feels as though these women’s individual fates were bound up with each other’s.

“I was coming off the Staple Singers Tour when I got a gig at the Pelican where Thoko Ndlozi was already a regular and a major hit,” Malebo told me during an interview in the early 2000s.

Joy, the South African female vocal group with members Anneline Malebo, Felicia Marion, Thoko Ndlozi. (Photo: Discogs)

“The Staple Singers, brought here by ET ‘Mshengu’ Tshabalala, of Eyethu Cinema and other enterprises, were a big deal then. You can imagine what opening for them did for my ego. I felt validated.”

It would not be too long before Marion and Ndlozi, and the third “girl”, Malebo, teamed up. Around this time Bernhardt, who long had nursed a dream of forming an all-girl group styled after US girl bands of the Motown and Stax era – the Vandellas, the Supremes, Staple Singers, the whole “she”-bang – saw an opportunity to plug the hole in his heart and in the culture.

Bernhardt was part of Joburg’s long-established Jewish showmen and women fate-bound with the African entertainment scene. The relationship went back as far as and beyond the late-1950s hit musical King Kong.

Bernhardt brought together the Soweto-born Ndlozi (30) with her chocolate skin and disarming smile, Marion (22), a Pietermaritzburg lass already immersed in US balladry, and Malebo (24), already a veteran showgirl who cut her teeth in the business working and touring with the “Cape Town invading advance guard” comprising Richard Jon Smith, Lionel Peterson, Jonathan Butler, Black Slave, and its predecessor, The Flamingos.

South Africa had seen nothing like Joy before.

Sure, there had been all-girl ensembles: The Dark City Sisters, Izintombi Zesi Manje Manje, the rotating members of the Mahotella Queens, and, even earlier in Sophiatown, the Quad Sisters and the most butt-kicking of them all, the Skylarks. But by the late 1970s most of them were yesterday’s news.

They were also thought to be neo-nativist acts put together to assuage apartheid’s cultural patrons’ preference for “rural” and “pure African past”.

Other than Fire Birds, a slick girl trio which Marion, Mandisa Nokwe and Mavis Maseko formed in 1975, there was nothing quite like Joy.

Joy was a perfect foil against black nativism, which had also infiltrated aspects of the Black Pride movement through cynical machinations that had nothing to do with soul dialectics and everything with tribalism and disruption of Black Unity.

With Ndlozi not only as the older and wiser lead singer but also the older and wiser of the trio – “the glue that held it together” – tall and ramrod-backed, an image and comport stuck between Cicely Tyson’s Negro-chic restraint and Gustav Klimt’s Woman In Gold; Joy was the stuff of Dream Girls.

Late-1970s South Africa was a period of decadence not experienced since the 1850s Gold Rush. It was decadent, but not in a Fellini sense of Satyricon, or Myra Breckinridge manner. Late-1970s South Africa was decadent also in retort and response to the stifling monster of censorship: unlike post-Rivonia Trial 1960s, the 1979s would not be cowed.

Joy was a perfect 1970s concept. Joy was contemporary. Joy was electrifying. In retrospect you’ll be forgiven for, wickedly, mapping them out as the Atlantic African ancestors of Destiny’s Child.

Here was a girl band with architectured, lacquered hair, translucent tops, fishnet stockings, sequined slit-leg numbers, American-style choreography and silky coos, for boos in love. Boy o’ boy, Papa got a brand new band!

Circa 1970s. Joy, the female vocal group performing live on stage. Seen here are Felicia Marion, Thoko Ndlozi and Anneline Malebo. © Arena Holdings Archives.

Since “Papa” Bernhardt is not around to speak of Thoko Ndlozi’s place within his Dream Girls, his daughter, 67 years old and long based in southeast London, UK, was more than happy to put a few things

in perspective.

“My father recalled me from England where I was due to attend university, in 1976,” said Linda. Stop everything and come check for yourself the most gifted and dynamic band you will ever work with in your life, Bernhardt instructed his daughter.

“I flew back reluctantly, unsure of what lay ahead. We are in the same age loop, but when I first met them, these young women, who had never been overseas before, just radiated confidence and curiosity.

“They were truly a band for the ages. And yes, Thoko was rather reticent. Although she was singularly stylish in her attire and how she comported herself, she gave off truly modest vibes. Well, she almost fooled me.”

“Those women were worldly but not world-weary. They had style. Thoko Ndlozi was the most stylish, and quieter. Their styles and characters complimented each other.”

Was it jarring to tour a band with no culturally fixed identity? Linda’s voice crackled down the line rather self-assuredly: “Joy was certainly a crossover act. They had a sizeable white, Indian and definitely coloured support base. All things considered, there was no mistaking the fact that they were a black township band. No getting around that.”

Numbers don’t lie.

“The bulk of their sales, fan base, and cultural factors were simply in the townships. ‘Crossover’ does not mean rootless or identity crisis. It simply means your art speaks to all kinds of people in the most visceral and soulful way.”

What I, a child of the 1970s, took from that is that contrary to the delegitimising tendency of ghettoising black artists, as though authenticity is exclusively borne out of sheer bleakness or perceived “chaos” abo-regional to the black experience(s), black music is, perforce, and out of spiritual foundationality, a “crossing over”, “crossing into”, “crossing back” and, literally, a “crossing with” aesthetic.

Joy was in lockstep with the townships.

As with them, townships were reservoirs of style. Everyone, particularly musicians themselves, understood the townships possessed an inner worldliness within the broader world.

“They were sophisticated, knowing and totally with it,” Linda Bernhardt tells me. “Not only were they the most interesting ‘game’ in town, as far as talent went, they were the only game. You could not be in show business and not understand how they operated.”

Bernhardt recalls that Ndlozi was, simply, a classy lady, far more mature in age and deed than her sisters in Joy. But there was no one particular leader. They all complemented each other.

Her recollections are echoed by Patric van Blerk, who would go on to helm another black pop act: Margaret Mcingana’s (aka Singana’s) We Are Growing, the theme song for the television drama Shaka Zulu.

Bridge

Van Blerk does not “speak” of Thoko Ndlozi, and of Joy, so much as have raptures about them: their quiet velocity, their complementary spirits, playful ticks, devotion to craft, the inner divinity of their divadom. Not to mention their growth into modern masters of compositional interpretation.

“They are hot, hot, hot!” chirped Van Blerk from Cape Town where he had relocated after the velvet curtain raised over the halcyon days of big mascara (and bigger dream) 1980s pop.

“They were truly a band for the ages. And yes, Thoko was rather reticent. Although she was singularly stylish in her attire and how she comported herself, she gave off truly modest vibes. Well, she almost fooled me.”

“I remember this one scene at Linda [Bernhardt] and Greg Cutler’s party in Yeoville, in 1982. Everyone started traipsing out of the house, one by one, and I was like, what’s going on here?”

He followed the smoke, only to discover that the prim and proper Thoko “had rolled the biggest spliff I’ve ever seen! That’s not all there was to her but that was a side of hers I simply didn’t see coming.”

He talks a beautiful rap. Well, he got the receipts for it. Hot off the tinkling din of memory tills. Memory fresh as sticky ink on unfurling paper. He speaks with an affecting bygone showman charm. Charm of a sequined and glittering past, leavened with a writer’s elephant memory.

He recalls Paradise Road as one of the quickest songs he ever worked on. “People ask me, how did you write it? And I say, ‘What? I don’t know.’ We never intentionally set out to write a political song. The song wrote itself.”

Verse

Come with me, down Paradise Road. This way please, I’ll carry your load. This you won’t believe.

There are better days before us. And a burning bridge behind us, fire smoking, the sky is blazing.

There’s a woman waiting weeping. And a young man nearly beaten all for love. Paradise was almost closing down…

***

This was hardly two years after Biko’s assassination and three after Soweto went up in smoke. While the words brazenly hew to the beatific, itself an act of pop as insurrection, considering the times in which the song was composed, by whom, for whom.

As far as lyric poetry, it was far from being The Wasteland the townships were waiting for. Paradise Road is candyfloss compared to music and poetry created by Black Consciousness groups and even disco punk outfits from the townships.

And yet, as a piece of music experienced on its artistic value, the song is a thing of unspeakable beauty, a flourish, and an outlet for pitch-perfect vocal ingenuity.

Almost 40 years later Paradise Road does not need your, or my, nostalgic love. In its instrumental sweep, roaring guitar chords, egged on by swirling, and squealing synthesizers, atop of which the girls, led by the sinewy vocals of Felicia Marion floated, is bewitching.

It baffles the mind that considering it was recorded with 1970s studio technology, it still packs a technologically futuristic kick.

With all its intense vocal and brass section drama, Paradise Road is ultimately a ballad. A heart-wrenching ballad, nonetheless. A ballad composed by two white men for three young black women – you’d think it’d reflect the apartheid dream come true, only it appended it and turned it on its ugly head.

The fact that the song attracted fans across all racial strata was a further kick to white supremacy.

But the song almost tanked into oblivion, and with it, our Joy. “I was frustrated,” says Van Blerk.

“I remember Phil Hollis, who was working with shit-hot township acts, telling me Joy was ‘not black enough’… That even the name Joy was not a black name! You could have felled me with a bird’s feather.

“All SABC channels rejected the song outright. For four weeks I pressed and handed out copies, no love. Until David Gresham broke it on his 5.30 Special on Springbok Radio. He played it three times in one show, and the rest is history.”

Circa 1980s. Joy, the female vocal group in the studio. Seen here are Felicia Marion, Thoko Ndlozi and Anneline Malebo. © Arena Holdings Archives

On 2 August 1980, the song debuted on Billboard’s Top 100. When Leo Sayer was scheduled to play Sun City, Joy was chosen to open for him. By that point, Sayer might have been huge overseas but Joy was bigger here.

Upon Joy’s return from their UK tour, Anneline Malebo announced she was pregnant and introduced her stand-in.

“Brenda Fassie was about 15 or so, shy, tightly coiled, kept to herself. Also, at that point, she did not have the soprano full range of Annie. When Annie sang her part, and in harmony with Thoko and Felicia, she practically floated over it. So did Felicia, while Thoko held it together with tenor, while splitting into free flights of her own. It was a magical experience to behold. Brenda was stepping into some spiky stilettos on the Leo Sayer night. I’m glad to say she held her own ground.”

Second verse

Temba, Mazakhele: Hammanskraal.

I was a pimply 12 years old or so when Joy’s comet ripped through our not so serene summer nights.

The neighbourhood disco-rock outfit, The Giggies’ Band of Temba Town, with their falsetto fiend of a lead singer, a yellow stick of a dynamite, skinny as Bowie as Ziggy Stardust, skinnier than Off The Wall Michael Jackson, and skinnier than that effete boy we called Patrick Yinde le Nyoni at Reneilwe Primary School, was on fire.

On our mothers’ Saturday laundry day, speakers, balanced on red Sunbeam polish tins, oohed, and aahed with the breathy voice of Donna Summer (“There will always be a you”).

Donna was a shape-shifting gangster in the body of MaMlambo, and a Creolised voice to discombobulate our hard-worn Sunday school-approved little souls. Donna was dangerous.

No, Donna please don’t. I swore by Aunty Lindi’s handkerchief which always had isi-rokolo that Donna would never whip my emotions any more.

And there was Diana Ross and her girlish purring (Touch Me In the Morning). Mnxm, that one: All styling gelled hair, synaptic energy; the whites of her eyes matching her gleaming teeth.

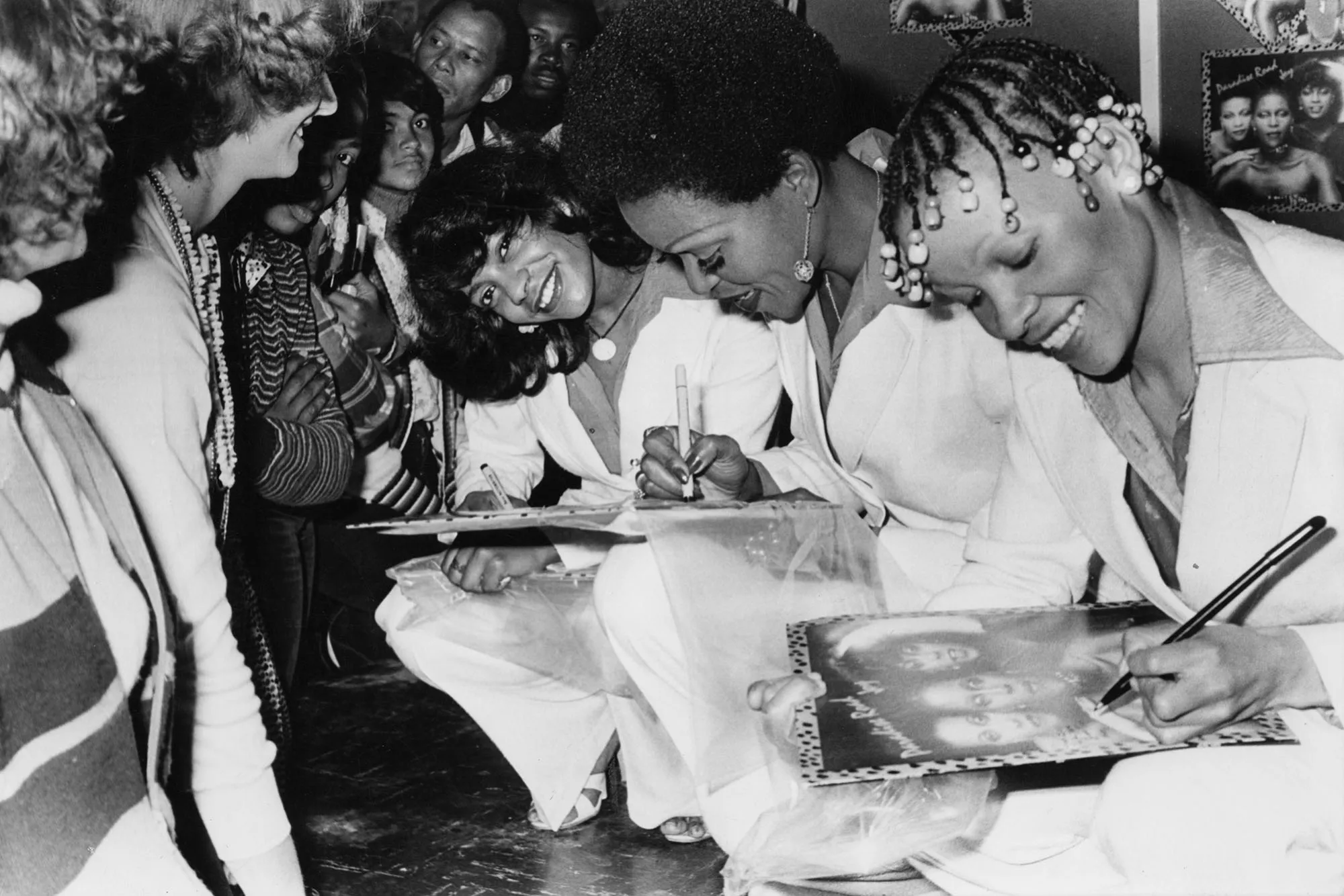

Circa 1980s. Joy, the female vocal group signing autographs in front of their fans. Seen here are Felicia Marion, Thoko Ndlozi and Anneline Malebo. © Arena Holdings Archives

At her most vulnerable, her songs commanded our uncles to touch her in the morning. What was wrong with these women?

What kind of African women didn’t have our mothers’ rolling hips and soft doughs of flesh under their upper arms?

Aunty Sekela said they were Negroes. She wanted to be a Negro too. The young boys suspected she waltzed in and out of her Negro fashion and wigs whenever we were out of sight.

We’d often sneak and take a peek through the keyhole, and looking at it – clearly Negroes, grabbed by the demonic spirit of pop songs, loved watching themselves on mirrors doing pirouettes – we shook our heads.

Which had the impact of leaving us both curious and confused about these Negroes our mothers spoke about with such aplomb. Not the way they spoke about whites in that suburb over the river Apies. Not even the way they spoke about mothers-in-law.

Falling off our mamas’ tongues, Negroes were clearly “the thing”. They certainly were mama’s faves, and who knows, papa’s too maybe.

We wondered then: If they are so slick and shit, “Do Negroes work for Baas Attie too, on weekdays? Or are they, like, kind of white in black skins? Why do they sing like birds and bellow like oxen?

Do they root for Big John Tate to hammer Kallie Knoetze’s teeth back into his Boer skull during their world championship fights?

Mshaye! Mshaye John Tate

u-Thata MaChance.

Mshaye’azafe!

We assumed that like Sydney Maree, who partly grew up down our street in Leboneng, still in Hammanskraal, John Tate was a local. Why not? He looked like a local. Unbeknownst to us he, too, was a “Negro.”

Well then, Negroes owned the world: In music they steal our mothers’ hearts away, reduce our aunts to pirouetting gift-shop figurines, and have the gumption to punch damn whites smack bang across the face.

Phew!

Joy, then, was never going to have a free ride. Not against those Negro women who spent all their laundry mornings asking to be “touched by strangers”.

Those Negro women could sing, yoh. If only they could stop crying and sing proper. Like the women at church.

But then Joy barged in via the wireless, elbowed out Negro singers, and soundtracked not only laundry mornings but all of our weekends. They were our mothers’ and younger aunts’ role models, not that we ever used such big words.

Women wanted to be like them. Men wanted them. Children howled in glee upon the band’s sighting on the telly for those who had “joined them whites and brought big wireless with talking pictures” into the lounge rooms.

Housewives shrieked. Sometimes just to annoy their husbands, who were shocked to realise their wives desired to have the same dangerous allure as their mistresses.

Joy soundtracked it all. Joy reflected it all: With their shimmering voices, in turns sinewy and commanding, sequinned numbers, “see-through” tops, God-taunting hemlines, choreography and attitude, the Joy “girls” were vigorous, bold and summoned freedom dreams in everything they did, stopped short of being licentious.

Ever since the group disbanded in the winter of 1983 (last show was at the Johannesburg Colosseum, on 6 June with Marion seven months expectant), I can count only a handful of local musicians with that sort of gutbucket (s)punk.

Shadiii, Brenda Fassie, and Lebo Mathosa. The running thread there is that all of these girl-trios were direct descendants of Joy, some even former members.

Although Joy possessed the rare charm of residing in your head so that you catch yourself involuntarily whistling their music, including another neon-lit sing-’long, Ain’t Gonna Stop Till I Get to the Top, this is what it all comes to: After the din of radio ebbs off… away, the Joy belles, essentially soul’d unrequited love.

Uncle William, and his “fresh as clean” friends, went on and on about how they wanted to pour the Joy dames some “pork”. They were not alone…

Outro

14 January 2021

Thoko Ndlozi, who has been politely “disappeared” off the news for the length of time equivalent to the years Nelson Mandela spent in prison, slept on her Dube Village bed and never woke up.

Born into an unassuming family – mother was a domestic worker, father a constable in the era where black police’s souls were ravaged by having to assuage the apartheid beast’s thirst for black flesh – the story of Thoko is the emblem of vivacious and vicious love.

It is the story of abundance of dreams, as it is the tale of bare threads.

It is a story of all who grew up on the “wronged” side of the global tracks; Jews in the ghettos, Southern blacks hanging on poplar trees, hillbillies in Appalachia, persecuted and lied-to Poles, etc, are all too familiar with this story.

But Thoko would not be caged. She would not hurl a stone in protest, either.

Imbued with the teachings, graciousness of spirit and emboldened resolve, against all odds, little Thoko, armed with no more than the beam of her smile, the rattle of the sequins, and one song – one dream, one love – helped to alter the world.

“Sis Thoko” had long been embalmed in our memory as a 1970s heroine – just so long as she “heroically” stayed at home and tended to her garden and sold lollipops and fizzy drinks from her house as all good township “heroines” are expected to.

In all those years of erasure I, too, never went looking for her. She was a statistic. Like a rolling stone/a complete unknown, and I would not have had direction to her home.

She was a discarded emblem of a cruel, cold world. It is because of that, that when news of her death rippled through the sky on 14 January 2021, I swore never to cry for her.

I felt she would have been mortified by the sight of casual strangers causing a scene in her name.

“Over my dead body.”

And yet. Still: there’s no Joy in our lives, without Thoko Ndlozi. DM

Bongani Madondo is a 2021 Writing Fellow at UJ’s Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study. His next book is Black Girls.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.