POETRY

Martyr to ‘morality’: Keats and the terrible burden of death and beauty

The 200th anniversary of the death, from TB, of English poet John Keats is marked on 23 February. How should we remember ‘poor Keats’?

The great English Romantic poet William Wordsworth died in 1850 and was succeeded as poet laureate by Alfred Lord Tennyson. Together these poets may be said to dominate English poetry during the greater part of the 19th century. Different though their works are, the course of their poetic reputations was similar and, taken together, demonstrate the fickleness of literary evaluation and reputation.

Friend and early collaborator, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, noted that Wordsworth’s work “produced an eddy of criticism”. Wordsworth’s first collection, Lyrical Ballads of 1798, was published anonymously, contained some of the greatest poems in English, yet was met with derision. Included were Tintern Abbey and Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, though even in the second edition of 1800, Coleridge’s contributions went unacknowledged, with only Wordsworth’s name on the title page.

Francis Jeffrey, in the very first edition of the Edinburgh Review, 1803, was scabrous in his account of Lyrical Ballads. Wordsworth was a “dissenter from the established systems in poetry and criticism;” the poems are examples of “false taste;” they degenerate into “mere slovenliness and vulgarity,” and represent the “positive and bona fide rejection of art altogether”.

About 15 years later when Wordsworth published his long poem, The Excursion, things hadn’t improved. Jeffrey famously began his review with, “This will never do,” and (in)famously concluded: “The case of Mr Wordsworth we perceive, is now manifestly hopeless, and we give him up as altogether incurable, and beyond the power of criticism.”

Keats died at 25 without having garnered the public laurels afforded the more long-lived laureates.

Tennyson’s first collection published in 1830 drew little mention. But his second collection of 1833 (actually published in December 1832) was savaged. The Literary Gazette wrote that the poet was of “the Baa-Lamb school” and suggested that “low diet and sound advice may restore the patient… ” In its Spring 1833 edition The Quarterly Review, the fearsome John Wilson Croker joined the slaughter. With acid scorn and irony, he classed Tennyson as “a new prodigy of genius,” and referred to the “peculiar brilliancy” of the poet’s work.

Despite being damned early on, both these poets ascended to the often dubious status of poet laureate. Tennyson – with some help from Queen Victoria who declared of Tennyson’s long poem of mourning and melancholia that, “Next to the Bible, In Memoriam is my comfort” – became what we might call “a celebrity”, a Victorian pop star, with more than 12,000 applications for tickets to his memorial service in Westminster Abbey following his death on 6 October 1892.

Despite their troubled critical beginnings, both Wordsworth and Tennyson are now securely lodged in that contentious thing, the “canon” of English literature.

This sketch of some of the critical fortunes of two great Romantic/Victorian poets is by way of introduction to another great Romantic poet, John Keats, who died 200 years ago in Rome, in a room across from the Spanish steps, on 23 February 1821. As with Wordsworth and Tennyson, Keats was flayed by critics from the get-go. Like them, he too is secure within the English canon. But unlike the hardier Wordsworth who lived to 80, and Tennyson who died at 83, Keats died at 25 without having garnered the public laurels afforded the more long-lived laureates.

Probably the most commonly known fact about Keats is that of his early death from TB, then known as consumption. But added to the representative tale of the “tragic” early death of a poetic genius – in the English tradition the death by suicide in a garret of Thomas Chatterton was already the most iconic example – was a further embellishment. It was not consumption that killed Keats, but scabrous reviews. Hostile early reception undoubtedly injured both Wordsworth and Tennyson. Keats it killed.

A number of people contributed to this legend, most notably Shelley in the Preface to Adonais, his “Elegy on the death of John Keats”. There he wrote that “savage criticism” of Keats’s early poem Endymion issued in “the rupture of a blood-vessel in the lungs” and that despite others’ acknowledgment of “the true greatness of [Keats’] powers”, these could “not heal the wound thus wantonly inflicted”. (Shelley’s use of the word “wantonly” is well chosen in its echo of Gloucester’s words from King Lear: “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods: They kill us for their sport.” The word makes clear Shelley’s view of the sadism of Keats’s reviewers)

(Photo: amazon.in/Wikipedia)

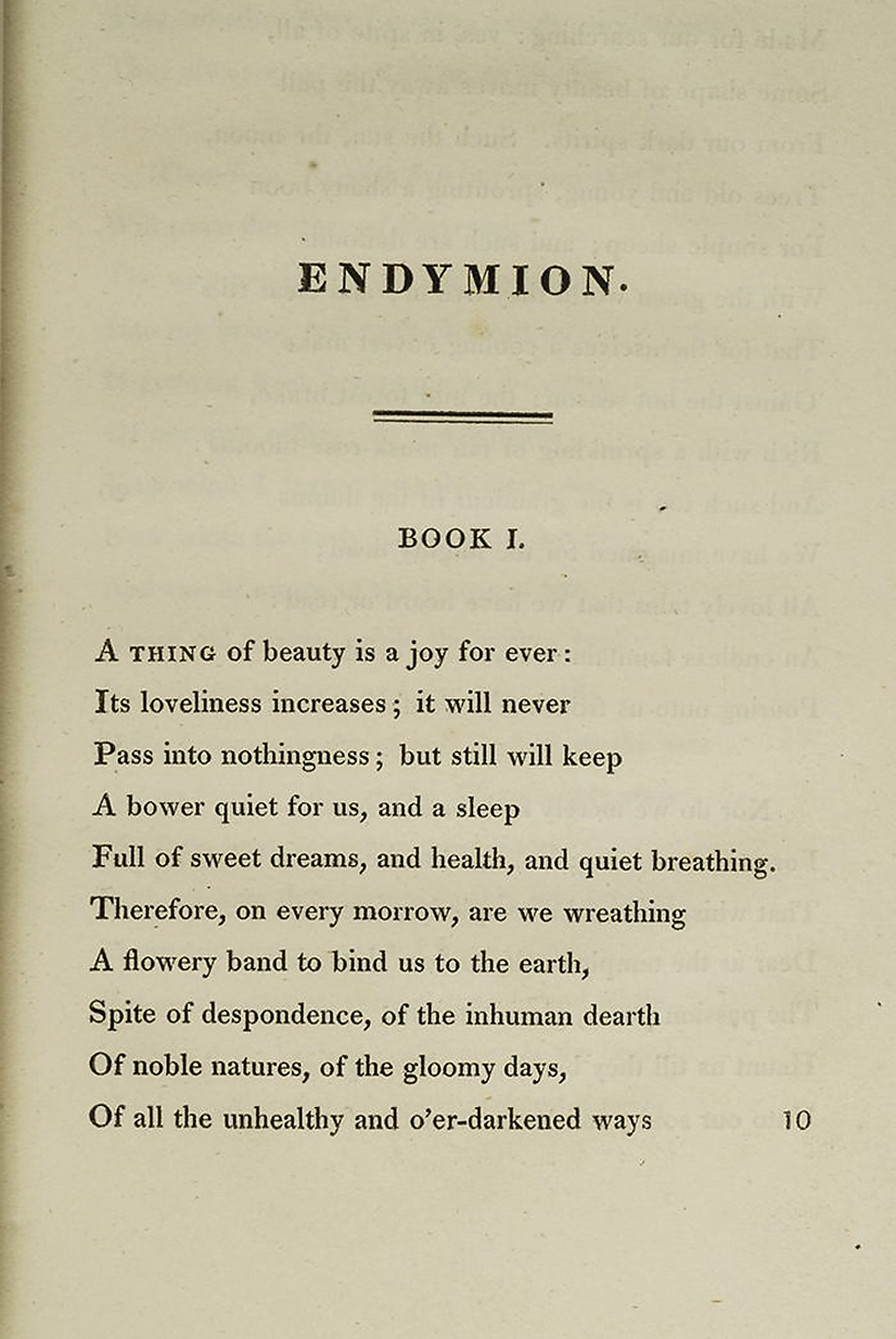

Poem written by John Keats. (Photo: pinterest.com/Wikipedia)

Lord Byron was not entirely persuaded by Keats’s powers, and this ambiguity is underscored when he wondered whether Keats’s life had been “snuffed out by an Article”. William Hazlitt, poet, philosopher and painter, acquainted with all the leading literary figures of the day, would add to the narrative by writing of Keats being “hooted out of the world, and his fine talents and wounded sensibilities consigned to an early grave”. For Hazlitt, with bitter acuity, the harshness of Keats’s early reception was meant to “serve as a warning” to anyone of “independence of feeling”.

Much later in the century, Oscar Wilde – of whom more later – added to the legend. In Wildean idiom, Keats was “the lovely Sebastian killed by the arrows of a lying and unjust tongue”.

After Keats’s first book of poems came out in 1817, the negative reaction was so strong that his publishers announced they would have no more to do with him.

All these accounts contributed to a sentimentalising of Keats commonly condensed – as in Shelley’s Preface to Adonais – into the words, “poor Keats”.

After Keats’s first book of poems came out in 1817, the negative reaction was so strong that his publishers announced they would have no more to do with him. Such was the “ridicule” the book attracted, that they undertook “to take the book back” from irate purchasers. The following year, Keats’s long poem Endymion was published and with it came a cascade of scorn. Among the most damning was none other than John Wilson Croker of the Quarterly Review, the man who went on to savage early Tennyson. Keats saw the poem as “a trial of my Powers of Imagination and chiefly of my invention” and admitted in its preface that it showed “great inexperience [and] immaturity”. Croker simply found it a trial. It was “unintelligible”, “nonsense,” “diffuse”, “tiresome and absurd”, and Croker could only bring himself to read one of its four books.

While Shelley seems to think it was Croker’s review that precipitated Keats’s death, far more damning was a review from Blackwoods Magazine. This review was part of a series of poisonous columns written by one “Z”, later identified as John Gibson Lockhart who, fittingly, would go on to become editor of the Quarterly. Wordsworth, because of his residence in the Lake District in the North of England, had been grouped together with Coleridge and Southey as “The Lake Poets”. (Byron wittily renamed them “the pond poets” and wished they “would exchange their lakes for ocean”).

In his first article of October 1817, Lockhart introduced a new group, “The Cockney School of Poetry”. Here the “chief doctor and professor” was Leigh Hunt, editor, poet and political activist who was jailed for two years (1813-1815) for libel against the Prince Regent. The coinage itself exposes the blatantly classist hostility to Hunt. Even without knowing anything of Hunt’s politics, the unabashedly political nature of the attack on him would be clear. Croker’s assault is little more than class bias. Hunt is accused of “ignorance and vulgarity”. Lockhart shows his true motivations when he writes that Hunt’s poetry is without “religious feeling and patriotic feeling”, and in his third article he writes that “our hatred and contempt” stem in part from Hunt’s “shameless irreverence to his aged and afflicted king”.

The extent to which aesthetic judgments are actually political prejudices is made clear when Lockhart turns his venom against Keats in the fourth of his articles. We might tend to think of Keats as the least political of the English Romantic poets. But his early association with Hunt’s radicalism blighted his reception. (Matters weren’t eased by Keats having dedicated his first collection, the Poems of 1817, to Hunt in a sonnet hastily written the night before the collection went to print). The brunt of Lockhart’s objection to what he called the “city sparks” stemmed from the perceived temerity of lower-class upstarts wanting to be poets.

Wordsworth, Shelley and Coleridge had been to Oxford or Cambridge with varying degrees of success. Shelley was wealthy, Byron an aristocrat. Keats was the son of an ostler and so from a relatively prosperous working-class family. He was apprenticed to a surgeon, went to medical school and left in 1816 having qualified as an apothecary, the lowest rung on the medical ladder. Lockhart’s “review” of Endymion is propelled by nasty classist malice. The poem is filled with “imperturbable drivelling idiocy”. Keats and the cockneys have the presumption to “look upon (them)selves as so many future Shakespeares or Miltons!” At best, Keats is “a boy of pretty abilities, which he has done everything in his power to spoil”. The political anxiety returns when Lockhart finds Keats contaminated by Hunt’s politics: “Their bantling has already learnt to lisp sedition.” Famously, Lockhart concluded by suggesting it is a “wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet”. “[S]o back to the shop Mr John.”

Far from returning to the shop, Keats assured his brother George that the Quarterly’s attempt to “crush” him was “a mere matter of the moment”, and “brought me more into notice”. His self-assurance seemed unfazed: “I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death” (25 October 1818). His attitudes towards criticism of his poetry, as towards most other things, was never stable. Already in April of 1818 he had assured a friend that “I have not the slightest feel of humility towards the Public”. He wrote that “my glory would be to daunt and dazzle the thousand jabberers about pictures and books”. Yet, with understandable self-commiseration, he would write in September 1819: “I have not been well-treated by the world.”

Keats was always ambivalent about his own abilities and the profession of poetry itself.

For Keats, the poetic ambition so reviled by Lockhart, was of greater moment than for most. He had abandoned medical studies to pursue a calling as a poet. The financial and vocational pressures of this decision worried him throughout his life. Though he had received a small inheritance – it is thought that the family lawyer did him out of a much greater sum – by May 1817 he was already highly conscious of what he called “that bill-pestilence”. These thoughts were inextricably bound up with his concerns over his poetic abilities and vocation. “Truth is, I have been in such a state of mind as to read over my lines and hate them… The Cliff of Poesy Towers above me,” he wrote to his painter friend, Benjamin Haydon.

Rather than a steady trajectory of improvement and growing confidence, Keats was always ambivalent about his own abilities and the profession of poetry itself. In the same letter to Haydon of May 1817, a few sentences after his self-doubt speculate as to whether Shakespeare was not his tutelary spirit: “Is it too daring to Fancy Shakespeare this Presider?” Less than a year later he wrote that he was “sometimes so very sceptical as to think Poetry itself a mere Jack a Lantern to amuse whoever may chance to be struck by its brilliance” (13 March 1818). The most radical expression of this famously occurs in his Ode to a Nightingale, where the poetry records that “The fancy cannot cheat so well/As she is famed to do, deceiving elf.” That Keats had himself invested so much in Fancy’s fame is a poignant irony.

Medicine might heal, but poetry might be a mere amusement, or worse, a trap. Like all the great English Romantic poets, Keats worried away at defining poetry and its place in the world. The huge claims the poets made for poetry demanded substantiation. Keats was the great sceptic of the imagination among his fellows and his ambitions and his scepticism ran hand in hand. In an early work Keats would claim that “the great end” of poetry was to “be a friend/To soothe the cares and lift the thoughts of man.” The friend analogy would return in Ode on a Grecian Urn where the urn is said to be “a friend to man”. Considering whether “Milton did more harm than good to the world?”, he concluded that the older poet was an “Active Friend to Man all his Life and has been since his death” (March 1818).

Poets “pour out a balm upon the world” whereas dreamers “vex it”.

In his late poem, The Fall of Hyperion, the poet/narrator debates the value of poetry and poets with one of Keats’s many goddess figures. Drawing on the medical analogy, the narrator stresses that a poet is “a sage,/A humanist, physician to all men.” Immediately he destabilises his claim, stressing that he “feels” that he is “none”.

Ruthlessly the deity accuses the narrator of being of “the dreamer tribe”, and distinguishes between the dreamer and the poet. Poets “pour out a balm upon the world” whereas dreamers “vex it”. Keats had always wanted to be a friend to man, not an irritant. This is the source of his view of poetry as a consolation and a therapy. His humanism is everywhere apparent. In January 1818 he wrote to a friend: “Men should bear with each other – there lives not the Man who may not be cut up, aye hashed to pieces on his weakest side. The best of men have but a portion of good in them… ”

Repeatedly he stressed a philanthropic urge. In April 1818, he wrote that “I find there is no worthy pursuit but the idea of doing some good for the world”. Repeated in October 1818 (“I am ambitious of doing the world some good”), the pressure of redeeming his defection from medicine is obvious. Nearing his own death, he wrote: “I could write a poem that I have in my head, which would be a consolation for people in such a situation as mine” (August 1820).

To be a humanist, physician and sage required specific effort. He might have abandoned medical studies but he claimed to “read and write about eight hours a day”. “The road [to doing some good] lies through application study and thought” (April 1818).

If reading poetry might “heal” others, writing it could be a balm to Keats. As his health and finances failed, noting the failure of his literary ambitions (“My name with the literary fashionables is vulgar”), he assured his brother George that whenever he found “[him]self growing vapourish” he would wash, dress neatly, then “all clean and comfortable I sit down to write. This I find the greatest relief.”

If Keats is most popularly known as the poet whose genius was tragically cut off, as “poor Keats,” he is also known for his commitment to beauty. For many he is a prototype of the aesthetic movement in England. Wilde, too, embodied this movement and became a sad example of martyrdom to English “morality”. His Picture of Dorian Gray is in many ways a novelistic reprise of many Keatsian dilemmas. Keats would have been gratified to know that Wilde certainly placed him among the English poets, writing that “this divine boy” was “one who walks with Spenser and Shakespeare, and Byron, and Shelley… in the great procession of the sweet singers of England.” In his sonnet, The Grave of Keats, Wilde continues one aspect of the Keats myth by referring to Keats as “foully slain” and invoking him as the “saddest poet that the world has seen!”

‘If I should die,’ said I to myself, ‘I have left no immortal work behind me – nothing to make my friends proud of memory – but I have loved the principle of beauty in all things. And if I had had time, I would have made myself remember’d’”

Importantly, Wilde claims that standing at Keats’s grave he “thought of him as of a priest of beauty slain before his time”. In Dorian Gray beauty is described as the “wonder of wonders”. Keats famously began the controversial Endymion with the words: “A thing of beauty is a joy for ever.” But we know that Keats – as Wilde was to do in Dorian Gray – struggled with the twin pulls of the pleasure and reality principles. In Ode to a Nightingale Keats would lament that “Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes… beyond tomorrow.” In Ode to Melancholy, this apprehension (I use the word advisedly) cannot be separated from the melancholy alertness to the interpenetration of beauty and death: “She dwells with Beauty – beauty that must die.” This obsession with beauty would lead the controversial critic FR Leavis to assert that Keats was the “only aesthete of genius”.

The fusion of beauty and death are related to Keats’s concerns about poetry and “life”, about the relationship between the “deceiving elf” and the death-devoted self. (Even the pun, dis-eving – Keats with Shakespeare is one of the great punsters of English verse – deepens this concern). These conundrums find one of their most affecting articulations in a late letter to his lover, the unfortunately named Fanny Brawne: “Now I have had opportunities of passing nights anxious and awake, I have found other thoughts intrude upon me. ‘If I should die,’ said I to myself, ‘I have left no immortal work behind me – nothing to make my friends proud of memory – but I have loved the principle of beauty in all things. And if I had had time, I would have made myself remember’d’” (February 1820).

The merciless self-assessment: This was a man who had written the great odes of 1819. The weight of those words “opportunities” and “but”. The sustained pressure of “the real” and its problematical interleaving with “Beauty”.

That death preoccupied Keats is unsurprising – as early as May 1817 he wrote that he “had a horrible Morbidity of Temperament”. Like Wordsworth, he was orphaned by 14. His father died when he was eight in a riding accident. Two months later his mother remarried and he was sent to live with his grandmother. Afflicted with TB, his mother later returned to die, and Keats nursed her through her final stages. He did the same for his brother Tom, who also died of TB. Then, unsurprisingly ill himself, he had to manage his own dreadful death.

In this he was assisted by his friend, the young painter Joseph Severn. Severn not only drew the famous sketch of the recently dead Keats, but catalogued the horrific details of Keats’s symptoms: how much blood he coughed up, his chronic diarrhea, and the colour of his expectorations. The extremity of their situation is underlined by one of Severn’s letters in which he wrote, “my spirits – my intellects and my health are all breaking down”. Then, horrifyingly: “no one will relieve me – they all run away.”

In May 1818, long before these dire days, Keats wrote a long letter to JH Reynolds. Characteristically, he hops about from gossip, to aesthetics, to philosophy. At one point he writes: “After all there is certainly something real in the world – Moore’s present to Hazlitt is real – I like that Moore… Tom has spit a leetle blood this afternoon, and that is rather a damper – but I know – the truth is there is something Real in the world.”

Nothing was more real than death. Unless, of course, it was the apprehension of beauty despite, in spite, to spite death. Within days of asserting that the road forward lay through application and study, Keats acknowledged that “an extensive knowledge is needful to thinking people – it takes away the heat and fever; and… helps to ease the Burden of the Mystery.” Ever sceptical, Keats was deeply suspicious of abstract knowledge, insisting that “axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses” (May 1818). Then, devastatingly, he writes: “It is impossible to say how far knowledge will console us for the death of a friend and the ills that flesh is heir to.”

(Photo: pinterest.ie/Wikipedia)

The “real” element in Keats’s life was a series of subtractions more devastating than is allowed by the “poor Keats” mythology, more devastating because, though horribly foreshortened, it is representative of all our narratives: “Circumstances” or the real led him to find his professional, emotional, financial and physical life threatened all at once. Even in To Autumn, considered by many to be a “perfect poem” in which Keats perfectly accepts “the real”, for me there is more than a hint of irredeemable loss. That autumn “conspires” with the sun gives us pause, as does the “fruit” of their conspiracy: “to load and bless.” The gift of fruitfulness is more than ambiguous – it is a burden (“load”) and the blessing speaks as much of the last rites as of an abundant donation.

Perhaps more than any other poet in the language, Keats dramatises the role of poetry in life, and sharply dramatises the fictions that inform its writing, as well as the realities that it cannot gainsay. From antiquity forward, writing has been one of man’s great instruments contra death. Keats shows readers both the necessity and futility of this effort.

Epilogue

I have steadfastly refused to comment on Keats’s “relevance to us”. The “relevance” of poetry is a topic beyond the scope of this piece. “Us” signifies a homogeneity of readership that cannot be legitimately invoked. To try to “justify” the reading of literature is a forlorn enterprise. To do so by stating that Keats “talks to us” because we are in a time of death and dying is to trivialise the poet’s own grappling with living, writing and dying. DM/ML/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.