COLD PEACE

Iran nuclear deal, v2.0?

After four years of seeming implacable hostility between Iran and the US, there seems to be the beginnings of — if not ‘a beautiful friendship’, at least the possibility of a return to a cold peace. That can’t be a bad thing.

It seemed like the six-power accord on Iran’s nuclear developments was an extraordinary event that was something from another age. Despite some 35 years of mutual hostility and distrust between Iran and the US, Britain, France, Germany, China, Russia — and the US — had achieved a limited, negotiated partnership with Iran to rein in the latter’s nuclear developments in 2015.

The ministers of foreign affairs of France, Germany, the European Union, Iran, the United Kingdom and the United States, as well as Chinese and Russian diplomats, announcing the framework for a comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear programme in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 2 April 2015. (Photo: Wikimedia)

For many Iranians, that mistrust actually began back in 1953, with the violent toppling of the government of the left-leaning but democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, at the encouragement or incitement of the Americans. From the perspective of the Americans, after what had seemingly been a close alliance with Iran under the shah, Reza Pahlavi, the 1979 revolution led to growing mistrust that became overt hostility because of the occupation of the US embassy in Tehran and the hostage-taking of scores of diplomats, once the shah’s regime had fallen. Concern grew still harsher as the Iranian government began espousing its revolutionary agenda towards the region more broadly.

The 2015 accord had restricted the number and effectiveness of those all-important uranium separation centrifuges. This was to contain the output of fissile materials (i.e. the all-important extent of U-235 concentration), thereby blocking, for as much as a decade into the future, the possibilities such material could be turned into nuclear devices.

This agreement was seen by many Americans (although not all) as a major success for diplomacy under president Barack Obama. While many Republicans strongly criticised the agreement for its obvious limitations over other Iranian activities and technological developments, as well as the release of a significant amount of Iranian funds long-held in escrow by the US, deeply experienced individuals such as Brent Scowcroft, the national security adviser under president George HW Bush, publicly supported it.

And for many on the international level, the agreement might also be read as a signal from Iran there was a kind of forbearance about those earlier angers on the part of Iran’s leadership in order to reopen economic connections, investment, and financial flows for the country. Moreover, it might also be read as an effort to tamp down the possibilities of direct, open warfare in the Middle East region, thereby modestly lessening the chances for hostilities between Iran and an ever-wary Israel as well. (Many Israelis were, to be fair, unconvinced about the reality of such a motive or its regional geopolitical impact.)

Not surprisingly, given the neighbourhood they live in, that latter nation has always been on the alert for the actions of an enemy or enemies who might push Israelis to consider circumstances that might become their national existential moment, and thus encourage the precautionary deployment of their own military — and even, just possibly, in extremis, lead to contemplating the deployment of those undeclared — but generally understood to be available — nuclear weapons. But especially after the tentative beginnings of regional rapprochement with several neighbouring Arab nations, for Israelis — following Iran’s 1979 revolution — they now see that nation to be the one most likely to set an open conflict in motion. Not surprisingly, Israelis have paid a great deal of attention to Iran’s nuclear potential, especially in connection with its development of its increasingly long-range missiles.

Given all these tensions and tripwires, the Iran nuclear six-party accord was also supposed to be able to offer some modest reassurances to Persian Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — whose fear of and hostile stance towards Iran was also a potential flashpoint. (The Saudis and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were, after all, engaged in hostilities in a civil war in Yemen, with Iranian-supported and supplied forces on the other side of that conflict.)

This six-power accord was also supposed to be a kind of signal to the world that the petroleum river that flows out of the Persian Gulf to power the globe would be in less precarious circumstances and subject to disruptions, now that at least one international agreement bound the Iranians to international norms.

In fact, during the remaining time of the Obama administration, the Iranians continued to adhere to the strictures of the six-party agreement, although they also continued to provide military materiel to groups in Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen. In addition, they kept up efforts to develop and test increasingly long-range missiles — the ostensible delivery vehicles for a future nuclear device — should they ultimately be developed, let alone deployed.

Then, when Donald Trump initiated his campaign for the presidency back in 2015, a key foreign policy hot button for him had been the Obama Iran nuclear deal, an accord he repeatedly called the worst deal ever. He brought it up incessantly, hammering away over the self-evident facts it did not restrict Iranian missile development, did not prevent Iranian support for various revolutionary groups in the region, even as it relaxed certain economic sanctions, and provided for the repatriation of funds that had been held in escrow by the US government for many years.

Playing upon that hostility towards Iran among many in the US, the six-party accord became a key argument Trump made that the Obama administration was soft on Iran and revolution, as well as heedlessly sacrificing the security of America’s allies and partners in the region, including the UAE, the Saudis, and the Israelis — for the chimerical benefits of the deal.

When Trump won the 2016 election, one of his early decisions was to withdraw from the six-nation accord, even as the administration also insisted Iran must continue to adhere to the accord, regardless. In response to that challenge, the Iranians slowly began to ratchet up their production of increasingly enriched uranium, even as they insisted publicly they had no intention of constructing nuclear devices. In reply, the Trump administration’s plan to press the Iranians was increasing economic pressures with new and more vigorous sanctions, on the theory economic desperation among ordinary Iranians would put sufficient pressure on the government that it would either change its ways or fall and be replaced by a government more amenable to American objectives.

However, the Iranian government did not fall. And ordinary Iranian citizens, while seriously upset over their growing economic hardships, as evidenced by major demonstrations during elections, did not ultimately rise up to demand sufficient economic changes that the government would bow to American demands in order to achieve self-preservation.

In January 2020, there was massive Iranian anger over the killing of Revolutionary Guard general, Qassem Soleimani, in (presumably) an American or Israeli remotely triggered attack. But the outrage in the massive demonstrations at his funeral was quickly overtaken after the Revolutionary Guard shot down a crowded commercial Ukraine International airliner on 8 January, just after it had departed from Tehran airport.

By the end of the Trump administration, the standoff between the two nations was at a stalemate. This was true even though the previous administration, late in the day, may have altered the larger regional geopolitical landscape in brokering agreements on diplomatic relations between Israel and Bahrain, the UAE, Morocco and Sudan, the so-called Abraham agreements. Although the Saudis were not party to such agreements, they now allow Israeli aircraft to overfly their territory.

But then, former vice president Joe Biden won the November 2020 presidential election with, among other pledges, his promise of a return to the six-power nuclear accord with Iran. Easier said than done, perhaps.

Nevertheless, as the AP reported, “The Biden administration says it’s ready to join talks with Iran and world powers to discuss a return to the 2015 nuclear deal, in a sharp repudiation of former president Donald Trump’s ‘maximum pressure campaign’ that sought to isolate the Islamic Republic.

“The administration also took two steps at the United Nations aimed at restoring policy to what it was before Trump withdrew from the deal in 2018. The combined actions were immediately criticised by Iran hawks and drew concern from Israel, which said it was committed to keeping Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons.

“Besides signaling Thursday a willingness to talk with Iran, the administration also reversed Trump’s determination that all UN sanctions against Iran had been restored. And, it eased stringent restrictions on the domestic travel of Iranian diplomats posted to the United Nations.

“The State Department announced the moves following discussions between secretary of state Antony Blinken and his British, French and German counterparts and as Biden prepares to participate, albeit virtually, in his first major international events with world leaders.”

The two nations — the US and Iran — are now positioning themselves to rearrange the landscape in a kind of competitive scene-setting in public over preconditions for the actual negotiations. On the Iranian side, that country’s chief diplomat has insisted that before there is any movement, the US must roll back American-imposed economic sanctions, and the US is saying the Iranians must renounce any drive towards nuclear devices.

Still, there appears to be some subtle movement forward. As The New York Times reported it on Monday, “Iran appears to have partly lifted its threat to sharply limit international inspections of its nuclear facilities starting on Tuesday, giving Western nations three months to see if the beginnings of a new diplomatic initiative with the United States and Europe will restore the 2015 nuclear deal.”

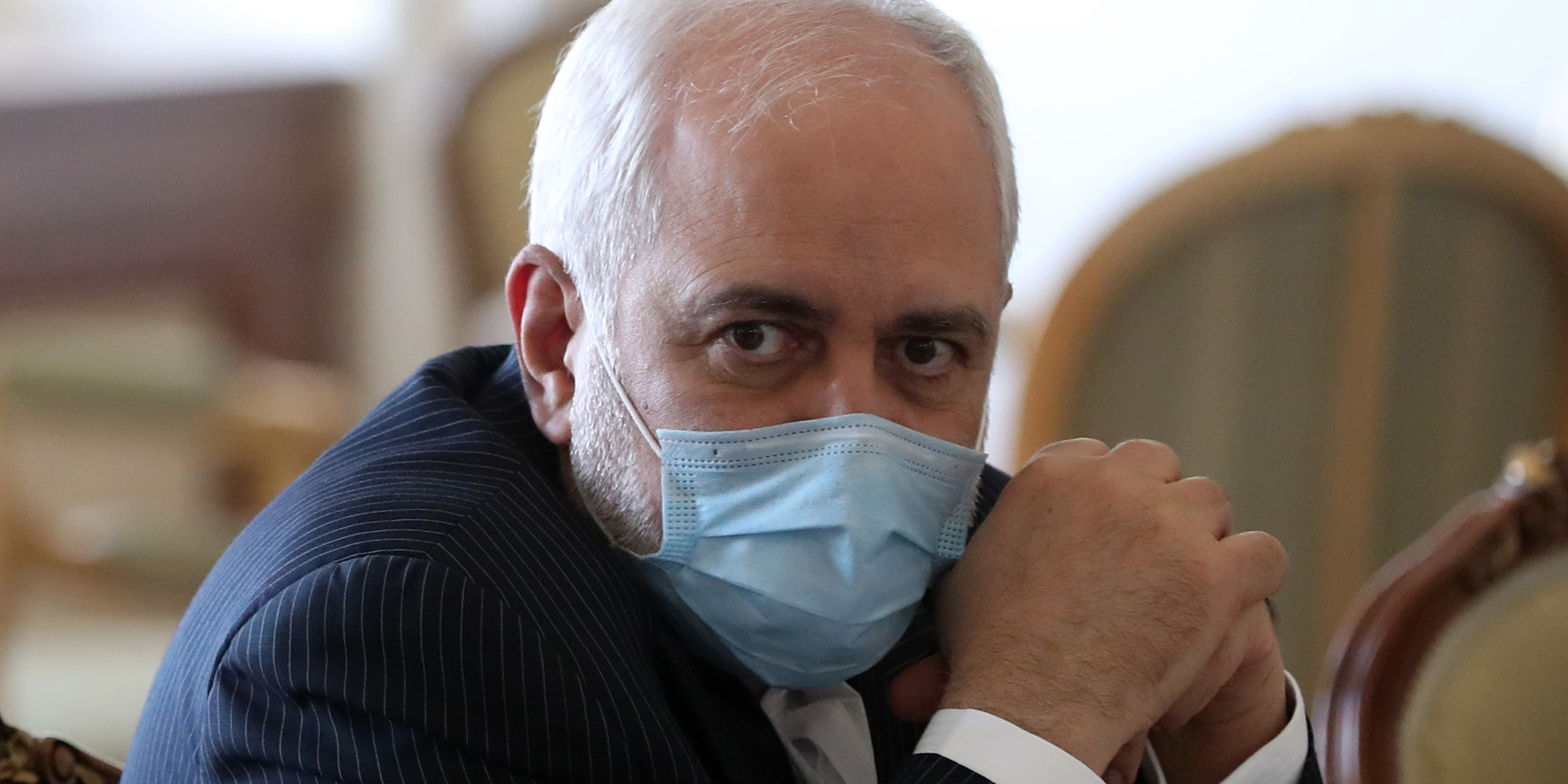

Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif during a meeting with IAEA director Grossi in Tehran, Iran, 21 February 2021. The director of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Grossi is in Tehran to meet with Iranian officials over Iran’s disputed nuclear programme. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Abedin Taherkenareh)

The Times of Israel (drawing on various reports) explained that because of Iranian parliamentary legislation and upcoming elections, Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has “urged US president Joe Biden on Saturday to act swiftly and return Washington to the 2015 nuclear agreement and end sanctions on the country by February 21, after which the Iranian government stance is set to harden”.

“The Trump administration re-imposed sanctions on Iran in 2018 after pulling the US out of an international accord aimed at curtailing Tehran’s nuclear programme.

“In an interview with the Iranian Hamshahri newspaper, Zarif said recent parliament legislation forces the government to toughen its stance on the US if sanctions are not eased in two weeks, Reuters reported Saturday.

“In December, the Iranian parliament, led by hardliners, passed legislation that set a two-month deadline for the easing of sanctions.

“ ‘Time is running out for the Americans, both because of the parliament bill and the election atmosphere that will follow the Iranian New Year,’ Zarif said. The Iranian New Year begins March 21. Zarif also pointed to upcoming presidential elections in Iran coming up in June. If a hardline president is elected it may further jeopardise the deal, he appeared to have suggested in the interview.

“ ‘The more America procrastinates, the more it will lose… it will appear that Mr Biden’s administration doesn’t want to rid itself of Trump’s failed legacy,’ Zarif said in the interview cited by Reuters. ‘We don’t need to return to the negotiating table. It’s America that has to find the ticket to come to the table,’ he added.”

Thus far, the jockeying is taking place in the open, rather than via quiet diplomacy in a well-guarded meeting room of a hotel in a cloistered spa town in Switzerland. In the meantime, the Biden administration has altered the heretofore crushingly close US embrace of Saudi Arabia and its efforts in Yemen (no more presidential sword dances or holding a mysterious glowing orb) that had been hallmarks of the previous administration, as well as ratcheting back the overwhelming love shown the Netanyahu government.

As the left-leaning Israeli newspaper Haaretz reported this course correction, “With the March 23 election and the battle against the pandemic in the background, the [Israeli] cabinet and the defence establishment are occupied with Iran’s nuclear project – amid Israel’s fraught relations with the Biden administration – and the ping-pong of threats vis-a-vis Hezbollah in the north.

“The longed-for phone call from Joe Biden finally arrived Wednesday. But there are several lessons in the fact that the president kept prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu waiting for a month. The new administration is working in an orderly fashion, speaking with leaders in accordance to the importance it attaches to each region. Despite the firm bilateral alliance, Washington has no intention of letting Netanyahu cut the line, especially in light of his deep solidarity with the Republican Party in the past decade.”

The other day, The New York Times also reported on this turn, “When the United States last tried to negotiate a nuclear deal with Iran, the reaction from the Israeli government was blunt and fierce. In the years preceding Iran’s 2015 agreement with Washington and several other leading powers, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel repeatedly called the negotiations a ‘historic mistake.’

“But on Friday, the formal announcement that the Biden administration was seeking a return to nuclear negotiations with Iran, after the collapse of the 2015 agreement under president Trump, did not provoke a sharp backlash — not just in Jerusalem, but also in the Gulf nations of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which also oppose too generous a rapprochement with Iran.

“The muted response from Iran’s regional antagonists may mask a strong undercurrent of pessimism and behind-the-scenes pushback against the Americans’ decision. Israel, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates remain wary of Iran’s intentions, and have signalled that they would be open to a deal only if it went well beyond the previous one — reining in Iran’s ballistic missile programme, its meddling in other countries and the militias it supports in Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen and elsewhere, in addition to its nuclear programme.

“Mr Netanyahu’s office issued a brief statement, avoiding direct comment on the American intention to negotiate, but noting that Israel was in contact with the United States.

“‘Israel remains committed to preventing Iran from getting nuclear weapons, and its position on the nuclear agreement has not changed,’ the statement said. ‘Israel believes that going back to the old agreement will pave Iran’s path to a nuclear arsenal.’

“Western diplomats and former Israeli officials said that the Israelis had accepted the need to engage constructively with Washington instead of dismissing the negotiations out of hand.”

Some of this evolution in positioning also may be coming from respective domestic factors. In the US, that automatic support of the Saudis ran into the reality of suspicions about Saudi Arabia, following the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate general in Istanbul and the wide acknowledgement of the brutality of the Yemeni conflict using US weaponry. Meanwhile, in the US too, there is more recognition that the current impasse with Iran may not be conducive to achieving a less dangerous Middle East equilibrium, as long as the ultimate resolution of the current impasse does not compromise Israeli security.

In Iran, it is also clear the current economic strictures as a result of sanctions will not lead to achieving the economic benefits the country’s citizens clearly are hoping to receive. And in Israel, the country is once again in the throes of yet another national election, with the current prime minister facing an electorate fed up with the deleterious effects on education from Covid lockdowns as well as the ongoing pressures of criminal indictments and possible trials for the prime minister. While preserving military security remains absolutely paramount among all politicians and voters, the tenor of Netanyahu’s approach may have worn thin. Another prime minister might even be able to envision a differently evolving regional political configuration.

Looking at the region holistically, Tamara Cofman Wittes, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank argued, “the Biden administration must re-establish clear boundaries in relationships that were deeply unbalanced by president Donald Trump’s careless approach. Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE all have questions about the extent and durability of American security commitments to their neighbourhood, and all three prefer to keep the US closely engaged.

“Washington can pursue necessary de-escalation and nuclear diplomacy with Iran while engaging these key partners about where American interests begin and end, and where partners’ own preferences and behaviours present real obstacles to closer cooperation. As in all healthy relationships, honest communication and clear boundaries are essential to maintain mutual respect and good feeling.”

Meanwhile, Ali Fathollah-Nejad, a non-resident Senior Research Fellow at Johannesburg’s Afro-Middle East Centre, and a former Iran expert at the Brookings Institution in Doha, argued, “Despite some official rhetoric to the contrary, there is no alternative for Tehran to such talks as Iran’s vital interests lie in stability-threatening sanctions being eased. Iran may, in fact, be willing in future to offer more concessions that could be proportional to the amount of US pressure.

But Iranians expect that pressure to ease as Biden’s administration drops the “maximum pressure” doctrine. The objective of Tehran’s current stance is to achieve a return to the position Iran had held before the 2013-2015 JCPOA negotiations when its advanced nuclear programme had offered the international community the bad choice between a rock (an Iranian nuclear bomb) and a hard place (bombing Iran).…” And maybe the governing strategy once again.

With all these modest moves and flexibilities now possible, it may soon be the time when real movement in what has been frozen in amber for the past four years can now occur. Maybe. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.