BUSINESS MAVERICK 168

Land reform and conservation meet on the banks of the Selati River

The Abelana Game Reserve is a study in a so-far successful community-private partnership.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

The history of conservation in South Africa counts many success stories, among them the saving of the white rhino from the brink of extinction. It also has a dark underbelly, one marked by apartheid exclusion and the dispossession of communities from their land to make way for wildlife.

Take for example the sharecropper Kas Maine, the subject of the magisterial biography The Seed is Mine by the historian Charles van Onselen. As the Pilanesberg game reserve and Sun City were being developed in the Bophuthatswana “homeland”, Maine was incredulous at the notion that he had once again to move off the land, but not for the usual reasons that had disrupted his life many times before in the face of modernity’s advance.

“… now there was a difference: instead of being threatened by advancing tractors and sprawling maize fields, which he could understand even if he did not like them, his oxen were having to make way for baboons, leopards and ostriches! It defied comprehension,” Van Onselen wrote.

Or take the Kruger National Park, regarded by many as the jewel in the crowning achievements of South African conservation. In his recent social history of the park, Safari Nation, Jacob Dlamini noted that the famed warden James Stevenson-Hamilton earned the moniker “Skukuza”, meaning “the destroyer”, because of his ruthless expulsion of more than 2,000 Africans from the park.

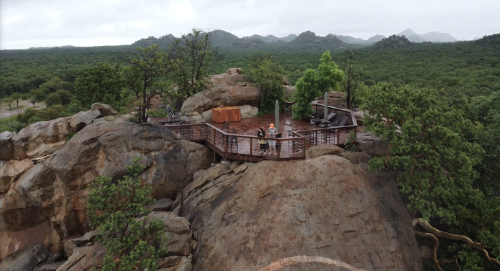

Now, this narrative is coming full circle: a dispossessed community reclaiming their ancestral land and using it for conservation, with an eye to economic development. It’s unfolding on the banks of the Selati River at the Abelana Game Reserve near Phalaborwa, where your correspondent recently paid a visit. About a decade ago, the Mashishimale community scored a victory in a landmark land claim that saw their land returned to them. Initially, the land was used for hunting purposes, providing employment to a handful of locals.

There has been a lot of debate (much of it emotive) about the economics of hunting versus the economics of ecotourism. The hunting industry also took a whack in 2015 in the wake of the killing of Cecil the Lion. One 2018 study found that trophy hunting contributed more than $340-million to the South African economy on an annual basis and that it supported more than 17,000 employment opportunities. Published in the peer-reviewed Global Ecology and Conservation, it examined the wider value chain. Other studies of hunting in Africa more widely – admittedly commissioned by anti-hunting groups in some cases – have found that ecotourism created far more jobs and made a far bigger contribution to GDP.

Ecotourism route

In the case of Abelana, the community eventually opted to embark on the ecotourism route and partnered with MTH Lodge Holdings to create an ecotourism venue on the roughly 15,000ha reserve. This initiative, rooted in South Africa’s recent history of land restitution and land reform, comes against the backdrop of many failed efforts and projects on this front.

But Wandile Sihlobo, the chief economist of the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa (Agbiz), who has written extensively on the issue of land reform, says projects that involve private partners usually fare better than those that don’t. “Land reform projects that involve joint venture partnerships between private sector players and individuals or communities tend to be more successful,” he told DM168.

So, how is Abelana faring?

According to Ian Beauchamp, MTH Lodge Holdings’ CEO, the reserve and lodge now employ close to 100 people, of whom 56 are drawn from the local community and 16 from nearby Venda. Guests pay a R100 levy a night that goes directly to the community trust. Laundry and other services have been outsourced to local businesses in the community.

“We had bad timing,” he told DM168 with a chuckle. “We opened in February last year and then had to close in March.” Still, the lodge is operational and is providing jobs in a region where employment in the local copper mines has been in decline.

“I drove around in 2017 and I just thought it had amazing features. We took it over in September of 2018 after three years of drought. I saw the ecological potential and the potential from a business point of view. They won it on the land claim and then they did a 50/50 [joint venture] with a hunting operation and they earned very little from that. Only seven people from the local community were employed,” he said.

The reserve is now lush and verdant thanks to the La Niña weather pattern, and is teeming with life. Bill Drew, one of the reserve’s guides, says he has identified 210 bird species in the reserve, which also has all of the Big Five minus buffalo (they are on order), stacks of impala, giraffe and zebra, and plenty of other species. With 65km of fencing and more game coming in, it is a long-term and capital-intensive project.

There has been some poaching during the pandemic and the economic meltdown that has followed – people have gone hungry – but Beauchamp says it has been nothing serious and he can live with the loss of a few impala. Such restoration of the landscape has been a common feature of South African conservation and agriculture in recent decades. The explosion of growth in game farming has seen much land previously used for cattle or crops turned over to wildlife, part of a wider trend that we now call “rewilding”. But community ownership of such land and partnerships with the private sector are relatively rare.

Michael Pilusa, who is a member of the local tribal council, told DM168 that the project was a long-term one. “People were removed in 1922 and it was painful; they were just dumped. That land is very important to us and it’s a game reserve now, so let’s keep it that way, even if it takes years. Our coming generations will gain skills and expertise to run such reserves,” he said.

Conservation dividends

There are clear conservation dividends from such projects: the return of wildlife and natural vegetation and things like that. The longer-term economic dividends await. Ecotourism is not a panacea – there is a reason why the Kruger is such a magnet for poaching syndicates – but there is no silver bullet for the challenges of rural poverty and underdevelopment in South Africa.

Tribal trusts and community property associations do not have a great track record when it comes to issues of transparency, so in the years to come it will be of more than passing interest to see how the money generated from the reserve is spent.

Still, in the wider sagas of South African land reform and landscape transition, it is vital that such community and private partnerships succeed. And job creation – South Africa’s most pressing social and economic challenge at the moment – has to start somewhere. Twinning it with conservation goals can be no bad thing. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

There are two ways that these community based schemes go wrong. The first is that the chiefs or indunas siphon off money into their own pockets and the second is that the population increases exponentially so that there is insufficient to go round.

Look at the success of Tembe Elephant Park. Another big mystery is why anti-littering campaigns are not in full swing.

Tourist destinations like Jozini and so many similar locations have become beautiful places that have been totally destroyed by something so preventable as indiscriminate pervasive littering.

All eco-tourism potential lost under the false belief that littering is actually job creation.

Educating against this can creatively be written into popular soapies. Creatives claim to love nature. Here is an opportunity to softly softly do something about it.