US STRATEGY REBOOT

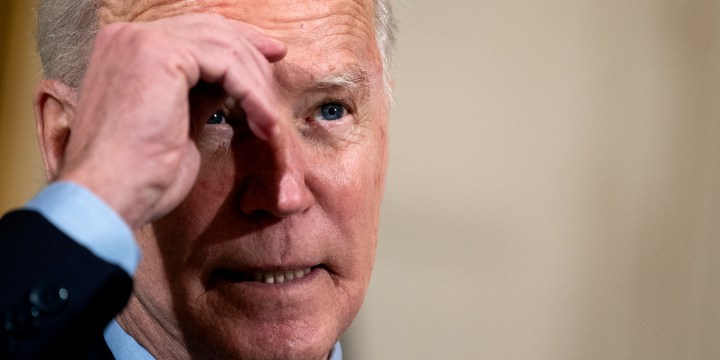

President Joe Biden takes first ride on the foreign policy roller coaster

New US President Joe Biden’s first major speech on foreign policy shows a very different style and ideas to those of his predecessor. But can the talk make the walk?

Building US foreign policy, in contrast to other government policy-making, is pre-eminently the province of a president and his (or her) government. One obvious example has been newly inaugurated President Joe Biden’s reassertion of the US’s participation in the Paris Agreement on climate and the centrality of climate/ecology/environmental concerns within foreign policy.

In the case of the Paris Agreement, because it was an agreement and not a formal international treaty, his decision required no formal, constitutionally mandated Senate approval to make it happen. Similarly, the Biden administration’s reaffiliation with the World Health Organisation (WHO) needed no immediate congressional agreement.

Of course, once a policy requires funding, Congress necessarily gets into the action. Even purely executive decisions can attract attention, and even tortuous, sand grain by sand grain examinations of presidential decisions and actions, or of the consequences of actions or inaction. The rationale here is that there must be congressional oversight of the executive, an essential part of the constitutional checks and balances order of things.

Consider, for example, the obsessive examination of the Obama administration, with 11 hours of questioning by a committee of a then Republican-led Congress of then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, in the wake of the death of the US ambassador and three others in Benghazi, Libya, in an assault on the temporary consulate by hostile forces. It may have been cringeworthy television, but it was within Congress’s powers.

Frequently, following a successful campaign that included proposals about foreign affairs, a newly elected president will seek to differentiate himself from the mistakes and policies of his predecessor, or to aim at new challenges for the new administration. After the complacent, self-satisfaction of the Eisenhower years, a young John F Kennedy had called for a new style of national sacrifice and promised “to get the country moving again.” Sadly, this kind of approach also contributed to a slide into what eventually became the Vietnamese quagmire and tragedy for the US.

And so it has been with Biden in this repositioning after his successor’s activities. But his reset has also come with some twists. This is a new beginning that intends to reach back to four years earlier, in order to reclaim what was deemed right and proper back then, and that can be so again. But it has also been set out with some differences from the policy of the president he once served. Moreover, this reset must take into account changes in the world’s geopolitical circumstances, changes that may make Biden’s journey more consequential and more difficult.

On 4 February, the president journeyed to Foggy Bottom, the part of Washington, DC, where the State Department’s headquarters is located, in order to deliver two speeches, to two rather different audiences. (In case readers were wondering, the name Foggy Bottom derives from the area’s historical circumstances as a low-lying, near-marshy bit of land, prone to fogs and mists coming off the nearby Potomac River. For critics, the nickname also refers to the turgid, bureaucratic prose and speech language that too often seems to emanate from the pens of those in that headquarters building. That building – along with its often-unloved denizens – is also sometimes referred to as “the fudge factory”. Diplomacy is not always loved. Now you know.)

Okay, back to Biden. For his first effort, the president spoke with hundreds of foreign service officers (aka US diplomats), and this speech must have been an enormous shock to them, despite their expectations, after the assaults of the past four years. The Biden administration is seeking its reset at home and abroad, and for foreign policy, morale among career Foreign Service officers who carry it out had dipped to new lows over the past four years in response to organisational tumult and policy incoherence. As Biden told his audience, “America is back. Diplomacy is back. You are the centre of all that I intend to do.” That surely was a shock to hear for many.

The president saluted the work of diplomats, reassured them he will have their backs, and he even applauded the role of diplomatic spouses and families. These are the people who bear the brunt of living in often-difficult, dangerous circumstances as they try to carry on “normal” lives regardless of their environment, and who live with the disruptions coming from intercontinental relocations every few years. After the degrading way diplomats (and their families) had been regarded by both of the ex-president’s secretaries of state (and the usual sneers by many in the administration and beyond, that foreign service families live in the lap of luxury, with all those hot and cold running servants and glittering dinners), to hear love from the government’s alpha dog must have been pretty shocking, but in a very good way.

Amid all this effort, over the weekend, the US president also delivered a virtual message to the African Union (AU) gathering in Addis Ababa where he stated: “The United States stands ready now to be your partner in solidarity, support and mutual respect.”

In those remarks, Biden described a shared vision of a better future with growing trade and investment that advance peace and security. As he remarked, “A future committed to investing in our democratic institutions and promoting the human rights of all people, women and girls, LGBTQ individuals, people with disabilities, and people of every ethnic background, religion and heritage.” (The Biden administration’s thoughts on Africa deserve fuller examination in a separate article, however.)

On Thursday, Biden’s first major foreign policy speech was a key element in the policy reboot. Its audience was global and it certainly has already been very carefully parsed in foreign ministries right around the world. There are some key takeaways already, foremost of which deal with Russia, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia/Yemen, and the country’s European allies.

As Michelle Bentley, reader in international relations at Royal Holloway College of the University of London, explained, “Delivering his first major foreign policy speech since taking office on January 20, US president Joe Biden has sent a strong signal to the rest of the world that they will see a very different America on his watch. In a wide-ranging address at the US State Department in Washington, Biden outlined his new foreign policy vision, declaring that – in what has become something of a catch-phrase – ‘America is back.’

“As well as communicating an important message to other international leaders about what the US will do over the next four years, the statement was also a public repudiation of many of the policies of the previous occupant of the White House, Donald Trump. It was a speech designed to restore order and global faith in the US, things that Biden clearly feels were lost under his controversial predecessor.

“US foreign policy will now focus more on multilateral diplomacy and working with other nations in a more positive way. But Biden stressed this should not be considered a soft approach, insisting that diplomacy would be the best way to get what the US wants: [as Biden said] ‘Investing in our diplomacy isn’t something we do just because it’s the right thing to do for the world… We do it because it’s in our naked self-interest.’ ”

With regard to Russia, Biden has made it clear that the forelock-tugging obeisance of the previous president is at an end. Instead, activities like cyber-hacking of the US government and other institutions must cease, along with behaviours like the possible offering of bounties on US military personnel stationed in Afghanistan. And while they are at it, repression of democratic activists like Alexei Navalny is uncalled for.

As Bentley went on to argue, “Addressing US relations with Russia, Biden said he had ‘made it clear to President Putin, in a manner very different from my predecessor’ that the US would no longer ‘roll over’ in the face of Russian aggression. He singled out ‘interfering with our elections, cyberattacks, poisoning its citizens’. He also raised the plight of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, demanding his release and condemning ‘Russian efforts to suppress freedom of expression and peaceful assembly’ as ‘a matter of deep concern to us and the international community’. All of this will be easier said than accomplished as it may well be that Russian leader Vladimir Putin has already calculated that his government has already achieved maximum benefit from his manipulation of the previous administration. Further, there are few additional sanctions that Americans could impose on Russia and its leaders, beyond those already in effect as a result of earlier transgressions.”

Meanwhile, Steven Pifer, nonresident senior fellow in the Center on the United States and Europe at the Brookings Institution (one of Washington’s premier think tanks), noted: “In his State Department speech, President Biden sharply broke with his predecessor regarding Russia. While President Trump seemed incapable of criticizing Vladimir Putin or Kremlin misdeeds, Biden took Moscow to task for the jailing of Alexei Navalny and crackdown on protesters, said the days of ‘rolling over’ to aggressive Kremlin actions were done, and pledged to work with like-minded partners for a more effective response to the Russian challenge.”

As things stand, the Iranians insist US sanctions must be rolled back before further steps take place, while the US wants any growth in refined uranium to be halted, along with hints that Iranian missile development and its support for its Hezbollah associates need to come to a close. There is obviously a gap between these two positions, but at least there is now diplomatic negotiation, rather than one of those large primate chest-beating contests. The prognosis? Not yet clear. Check back later.

Concerning China, here the Biden administration has agreed with his predecessor on at least one thing. This is that the US’s primary strategic challenge in this century has now become the Chinese challenge, rather than that still-very-real Russian one, although the Biden strategy will be different from his predecessor’s. The China challenge includes an ongoing economic competition, the larger regional and global geopolitical balance, and even a contest of ideas about the shape of the future global international system.

Ryan Hass, senior fellow in the John L Thornton China Center and the Center for East Asia Policy Studies, also at the Brookings Institution, explained: “President Biden’s treatment of China in his first foreign policy address signaled that he views China as a central challenge, but not a burning issue that eclipses all other concerns. Biden embedded discussion of China within his survey of risks and opportunities on the international horizon. Biden emphasized that China poses significant challenges to America’s interests and values. To respond effectively, Biden argued, America will need to rebuild leverage, e.g., by pursuing domestic renewal, investing in alliances, reestablishing U.S. leadership on the world stage, and restoring American authority in advocating for universal values.

“Such an approach marks a departure from the previous administration’s framing of U.S.-China relations as an ideological and Manichean good vs. evil struggle. Biden clearly has no qualms about pushing back firmly against China, but he signaled that he intends to do so purposefully, with an eye toward advancing American interests. This includes cooperating with competitors when it is in America’s interests to do so. Even as it will take time for this shift in approach to take expression in specific policies and actions, there should be little doubt that President Biden and his team have their own views of how the United States can outcompete China. Much of their work will focus on efforts at home, with allies, and on the world stage. The shifts may be subtle and may not generate daily headlines. But with Biden’s speech, a course correction on China policy appears to be underway.”

Thus, the Biden strategy, in contrast to the previous president’s go-it-alone-America-first-speak-loudly-and-carry-a-teensie-tiny-stick, is going to need to embrace more vigorous economic competition (including trade promotion), maintaining deliberate, consequential responses to provocative Chinese military manoeuvres and actions in the waters surrounding southeast Asia, and asserting the fundamental superiority of democratic principles and ideals. The crucial difference with the previous administration will be a core principle that such competition must be carried out in conjunction with US allies in the region and beyond. This will be particularly important in dealing with the South China Sea region, the issue of freedoms in areas like Xinjiang and Hong Kong, the continued viability of Taiwan, and the level playing field of transparent trade and economic relations. All of this will be easy to say, but harder to achieve, of course.

Right behind these two concerns are the circumstances of the nuclear accord with Iran. The Biden administration has made it clear it wants to reassociate the US with this agreement, and initial signals from Iran have been that such a thing is certainly possible, although the two nations have very different ideas about what must happen first and who must budge in what way, before progress is real.

As things stand, the Iranians insist US sanctions must be rolled back before further steps take place, while the US wants any growth in refined uranium to be halted, along with hints that Iranian missile development and its support for its Hezbollah associates need to come to a close. There is obviously a gap between these two positions, but at least there is now diplomatic negotiation, rather than one of those large primate chest-beating contests. The prognosis? Not yet clear. Check back later.

But the US-Iran dance leads directly to the doleful circumstances of Yemen, where the Iranians and Saudi Arabians (with the support of the US) are backing opposite sides in a gruesome civil war over the now-shattered country of Yemen. Still, in response to a growing clamour both in the US (including continued anger over the death of Jamal Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul) and abroad, the Biden team is closing down support for Saudi military efforts in Yemen.

The world Barack Obama dealt with is significantly different from the one the new president must deal with. In the Obama era, it was still possible to see Russia as a relatively minor irritant on US hegemony, and to see the Chinese as a growing but not yet all-encompassing challenge to the US’s prospects. In Obama’s time, the key, most troublesome foreign policy focus might still be seen as centred on an arc that ran through the Middle East and on to Afghanistan. It no longer can be the central focus of policy.

There is clearly a knock-on effect from this on to the tacit alliance between Saudi Arabia, other Gulf Arab states, and Israel directed against the real and potential threats represented by Iran’s military prowess and its support for groups in Syria, Yemen and beyond. Beyond that, there have been periodic Iranian threats to shut down the Persian Gulf for those massive oil and natural gas exports from the region to the rest of the world.

Here, in addition to the Biden administration’s efforts directed towards Iran and the six powers’ nuclear accord, this decision on materiel for Saudi military efforts in Yemen represents a real break with the previous administration. There certainly will be no Biden visit to the Saudi king to pay obeisance and kiss his ring, to hold that weird, glowing orb, or join in a sword dance. But the changed nature of the Middle East strategic balance following the “Abraham Accords” is unlikely to be unravelled, despite this drawdown on support for Saudi actions in Yemen.

For the remaining key issue that we shall note here, the way the Biden administration will be dealing with the country’s allies, it has already been reported widely that the foreign ministers of Germany, France, and Britain and the US secretary of state have said they plan “to revive” the transatlantic relationship, following their first in-depth talks since Biden took office. This obviously will be more complex than a simple agreement on every issue and regarding every conflict globally. But it certainly will be very different than that “go it alone” stance that typified the previous administration, and the public disparagement and distancing – or worse – from any ideas on coordination, save on US terms.

There are obvious possible speed bumps for such approaches, such as German plans to import Russian natural gas, regardless of the status of any disputes with that nation. There are, as yet, no agreements on tight coordination over trade disputes with China, and there are many interests among European nations willing to increase trade with Iran, almost regardless of political consequences from the US perspective. But it is crucial to state broad allied coordination as a goal.

Finally, while it has been easy to see the Biden administration as something like the third Obama administration, differences must be noted as well. First, of course, we should recall that Biden as vice-president was the one senior voice in the Obama administration who spoke out within the Oval Office against committing more troops for an Afghan surge in 2009. That should argue that Biden may be even less willing, unless vital national interests are at stake, to commit direct military force to conflict zones.

Simultaneously, the Biden administration has already indicated it views the security of the US’s European allies as a vital national interest in effectively cancelling the previous administration’s plan to draw down on US forces based in Germany. Accordingly, as the president noted in his speech, observers should watch for a much more aggressive, muscular diplomacy as the first means of projecting national interest, rather than the threat of military force.

But there is another fact to keep in mind. The world Barack Obama dealt with is significantly different from the one the new president must deal with. In the Obama era, it was still possible to see Russia as a relatively minor irritant on US hegemony, and to see the Chinese as a growing but not yet all-encompassing challenge to the US’s prospects. In Obama’s time, the key, most troublesome foreign policy focus might still be seen as centred on an arc that ran through the Middle East and on to Afghanistan. It no longer can be the central focus of policy.

Just a stray thought here. Perhaps it is time to make a great reach back to the Nixon triangulation that led to a rapprochement with China to balance the Soviet Union. Now it may be time to find a way to work more effectively with Russia to help counterbalance a surging China. Or, perhaps, with sufficient effort, the Biden administration can build deep cooperation with European friends into a solid front that can address China’s efforts. Going forward, it will be critically important to see just how adroit the Biden administration can be in its geopolitical grand strategy. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.