Maverick Life

The wasp that cares a fig

It’s said that if you lift up the corner of anything, you’ll find it’s hitched to the rest of the universe. As mutual dependence goes, though, you’ll seldom find a closer – or odder – relationship than between a fig tree and its personal wasp.

There were chimpanzees all over the fig tree like fat brown fruit ripe for the picking. They were eating, arguing, posturing, playing and one couple, unconcerned by a cluster of admiring youngsters, were fucking.

Bits of discarded fig and the occasional scat or stream of pee were raining down. Given the massive spread of the tree’s branches and the closeness of the surrounding forest, it was hard both to see the chimps and avoid being splodged.

I had hiked to the huge fig tree at the heart of the Kibale Forest in Uganda with a guide and a small group of primate enthusiasts. We stared at the Pan troglodyte performance for a while, as one would, but I gradually became aware of the sideshows – countless birds and periodic raids by nervous red-tailed monkeys. The tree was aswarm with life. Down below, the ground was covered in rotting, marinating figs and buzzing with all manner of intoxicated insects. After the silent, confidential forest, it was like entering a supermarket with a summer sale on.

Fig tree

Fig tree

There’s just something about fig trees that, like baobabs, sets them apart. Strangler figs spiralling their way up forest giants and looking like Jack’s beanstalk, rock figs clawing their way up cliff faces and here, a Zanzibar fig, crawling with chimps. They have presence.

Because they fruit all year round, fig trees – all 750 species of them – are the very foundations of tropical and subtropical life. They’re more than mere trees: they’re entire ecosystems.

Depending on its size and type, a tree can yield up to 100,000 figs twice a year (we’re talking tonnage here) and each fruit can contain up to 1,000 tiny seeds. This makes for some serious eating by an extraordinary range of creatures.

South African naturalist Duncan Butchart, who staked out a large Stuhlmann’s fig in Maputaland, ticked off 16 trumpeter hornbills, 10 African green pigeons, eight purple-crested louries, eight white-eared barbets, seven black-bellied starlings, six speckled mousebirds, six yellow white-eyes, four black-eyed bulbuls, two black-collared barbets, a golden-rumped tinkerbird and a solitary sombre greenbul, all of which visited the tree within 30 minutes. This definitely beat counting partridges in a pear tree.

But that hardly scratches the surface of fig-tree society. While the parrot-like green pigeons are the standard rent-a-crowd in fruiting figs, you will invariably also find several species of lourie and hornbill. Patient observation might also turn up African pygmy geese, white-backed ducks, twinspots, canaries, fire finches, francolins, guineafowls, geckos, agamas, arboreal snakes, tree frogs, dragonflies, wasps, damselflies, fig tree moths, spiders, ants, termites and the beautiful fig-tree blue butterfly.

Then, depending on the tree’s location, there are fruit bats (Wahlberg’s and Peters’s epauletted, straw-coloured and Egyptian), samango and vervet monkeys, galagos, baboons, chimps, gorillas and, of course, humans.

At ground level you may find elephants, several species of duiker, bushpigs, African civets, dassies, squirrels, mice and other rodents, tortoises (which love munching fermenting fruit) and, if the tree overhangs water, banded tilapia and silver catfish which snap up floating fruit. Under the mulch and fallen figs are no end of sap-sucking beetles, weevils, slugs and bugs.

I guess you get the picture. But here’s the amazing bit.

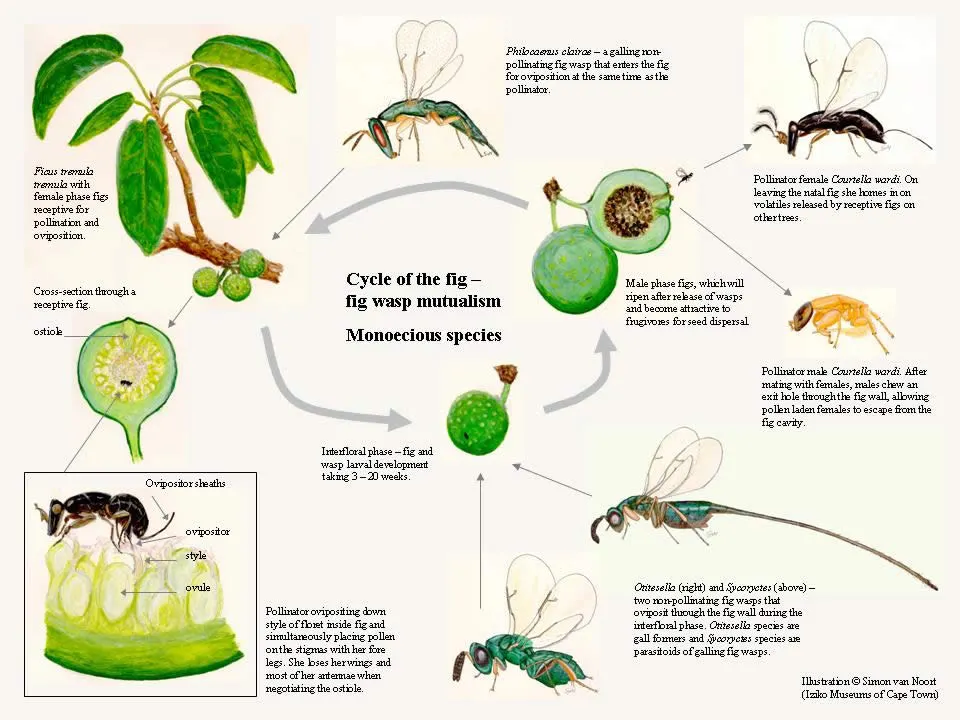

At the base of this extraordinary balancing act of interdependence is a creature the size of the head of a pin and a fraction of its weight: the fig wasp of the family Agaonidae. Each of the hundreds of Ficus species has its own, private and personal pollinating wasp. Without the wasp, the only evidence of the genus Ficus would be in coal or fossil deposits, but without a fig, the wasp is but a faint memory.

Illustration Iziko Museums of Cape Town

The fig wasp is involved with figs the way fish are involved with the sea: they live and have their meaning within its enfoldment. It’s one of the most extraordinary examples of co-evolution. In fact, it has been suggested that the tree and the insect have co-speciated: when new species of fig evolved, the wasp evolved to pace its needs.

If you’ve ever eaten a fig you’ll know that it’s an enclosed sphere which, when you break open, contains what looks like a deep-pile carpet of edible stuff. The ‘pile’ is not flesh but flowers, hundreds of them. To breed, the tiny female wasps have to squeeze their way through a tightly closed opening (the ostiole) at the apex of the fig to get into this sphere and to do this they have developed what entomologist Simon van Noort of Iziko Museums in Cape Town described to me as “quite bizarre morphology”. On his desk was a display case of several hundred wasps and a microscope. “This is the only way you can appreciate them,” he commented as he adjusted the scope’s focus.

Suitably magnified, the wasp certainly was bizarre – but beautiful. She had an elongated head and a flattened thorax, delicate mandibles and backwards-pointing teeth to prevent her slipping backwards while boring, a few teeth on her legs for good measure and two delicate, fan-like antennae. With this equipment, she has to squeeze and labour her way into the fruit before some predator comes along.

“It’s tough getting into a fig if you’re the pollinator,” Simon observed. “Her wings and antennae usually break off. But she doesn’t need them once she’s inside.”

Within the protective fruit, which seals the hole she’s made, the wasp lays her eggs in some of the flowers and pollinates others with pollen she’s conveniently stuffed into pockets on her legs or which has stuck to her body. Then, in her tomb blossom, she dies. A lifespan of but a few days.

When her offspring are mature they hatch into the enclosed world of the fig. The generally wingless males – runty little things – have what from a non-wasp perspective seems a short, unenviable life measured in mere hours. They chew holes in the galls containing the young females, mate, dig exit tunnels through the fig wall from which the females escape, then die.

The females see a bit more of the world. Some trees have figs that perform both the male (pollen production) and female (seed production) functions, but others – around half of all figs – have separate male and female trees. In this case, the female trees produce figs that have only seeds and the male trees figs that produce only wasps (you may be relieved to know that the edible fig we enjoy comes from only a female tree.)

Once the female wasps have left the fig, the fruit ripens, changes colour and smell and becomes attractive to fruit-eating creatures which dutifully disperse the seeds.

For a tiny wasp on a mission, finding the right fig is solved by the tree, which emits a perfume cocktail attractive to only that special wasp which pollinates it. Just to make it more challenging, the tree remains receptive to wasps for just a few days, but it makes sure it presents its pollen on exactly the day the adults emerge from the fig.

It can be pretty rough outside the protective fruit, which may explain why the males stay put. As the females emerge, ants, birds, geckos and even flies snap them up. But, luckily, the fig only ripens after the wasps have left and so fruit-eaters don’t chomp the pollinators of the next fig crop.

Once out, the females sniff their way up the scented trail, regularly clocking up to 10 kilometres. The record, though, presently stands at 450 kilometres, clocked between KwaZulu-Natal and Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape – and this is an insect around a millimetre long. You try to figure that one out.

So the wasp locates a fig to ensure the continuation of her species, and the tree makes sure that its pollen reaches future generations by the only way that it can – in the knee pockets of a near-microscopic insect. Neither could survive without the other.

You might wonder how the tree got this orchestration just right. Recent research suggests that fig trees and wasps have been refining their mutualism for around 90 million years. If the wasps fail to find their goal and pollination doesn’t take place, a tree (almost as an act of chagrin) will commonly abort its entire crop.

Just in case you think that’s the end of the story, you need to know there are hundreds of species of parasitic, non-pollinating fig wasps that the tree does its best to ignore and countless mites and nematode worms that live in the figs and travel and propagate by way of fig wasps. There are layers upon layers of mutualism and co-evolution out there which we’re only beginning to get a handle on. A British mathematician, Augustus de Morgan, seemed to get it right when, after puzzling over life’s interconnections, wrote:

“Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum,

And the great fleas themselves, in turn, have greater fleas to go on,

While these again have greater still, and greater still, and so on.”

I’d love to know what he’d think about fig wasps and that tree full of chimps in Uganda. Probably he’d nod and say: “Just so.” DM/ ML

Here’s a video of the process.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Amazing! Always a great read, thanks Don

Totally amazing: the web of life!

Brilliant, as usual. Thanks, Don. My fig knowledge just increased exponentially. Keep ’em coming 🙂

Bravo!

You couldn’t make a saga like this up. Rich with adventure, fraught with danger, kinky sex, tight plotting, distracting but relevant sub-plots. Far stranger (though similar to) the Quangle Wangle’s hat.

A marvelously insightful perspective on the things and processes that surround us ! Maybe next time you can add the species that made the greatest interconnection, by making a country “great…. again!!”