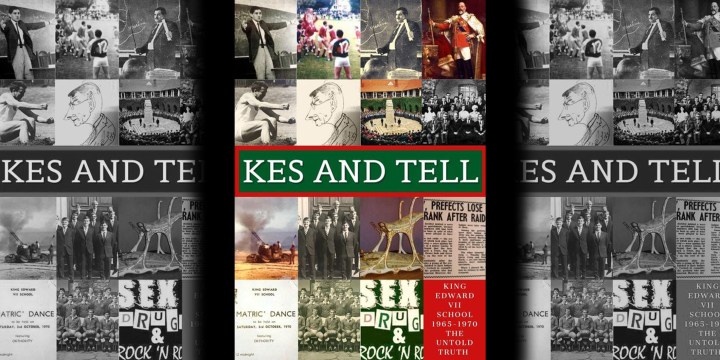

BOOK OVERVIEW

KES and Tell: King Edward VII School old boys use Covid-19 lockdown to revisit ‘The Year of the Plague’

‘Every boy at school maintained a high level of vigilance, like impala carefully approaching a waterhole, because one never knew when the stick might strike or for what reason.’ A no-holds-barred collection of tales of school life by some of those who passed through its corridors.

When Covid-19 put a spanner in the works, the 50th anniversary reunion of the King Edwards VII School (KES) class of 1970 was cancelled. Old KES boys used lockdown to produce an unauthorised, unapologetic, often scandalous version of the history of their time at the school, provocatively titled *KES and Tell. With no holds barred, the 50+ contributors laid bare the endearing eccentricities, foibles, perversions and sadistic bents of the teachers of their time, none of whom – auspiciously – are still in the land of the living.

The 1970 matric class earned the title “The Year of the Plague” because for the first and only time in the 120-year history of the school, the head boy and prefects were demoted; their crime being to take revenge on a merciless science teacher known as “Dumbo” Benjamin by raiding and trashing his garden and throwing stones on the roof of his house. Dumbo, named for his large ears, was renowned for dispatching boys to the school principal on the slightest pretext, for “six of the best”.

Former Intelligence Minister and KES old boy Ronnie Kasrils. (Photo: Gallo Images / Beeld / Cornel van Heerden)

Ronnie Kasrils (a KES survivor from a decade earlier) suggests mischievously that “The Year of the Plague” could well be the subject for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “Archbishop Tutu would happily exult in the message of the title,” he said. “The roost was ruled back then by the most vicious corporal punishment to keep boys in line. The title could well have been ‘KES my arse’.”

“There was only one disciplinary procedure in those days and that was to hit the shit out of us from morning to night,” Tim Haynes says.

The four editors of the book, Tim Haynes (Johannesburg), Derek Hewitt (Miami), Donald Macdonald (UK) and Michael Rakusin (Sydney) produced the book using Zoom. They were unanimous in their determination to tell the truth. “Our behaviour as students was very much at odds with the classic, starry-eyed vision of typical KES young gentlemen,” Derek Hewitt writes. “Now that the Statute of Limitations has expired, we are telling it like it really was.”

The 1960s-1970s were challenging times for adolescent boys at KES: apartheid, Sharpeville, censorship, the Vietnam War; a global Cultural Revolution – and compulsory military service looming on the horizon. The impact of these multiple influences was intensified by the school ethos which revolved around the relentless practice of corporal punishment and the veneration of British military traditions.

“I was on the receiving end of that colonial legacy myself back in the 1950s. If only my schoolmates had been as unconventional as the 1970 generation I would not have been regarded as such a malcontent. The discerning reader will recognise their spirit influenced by the emergent anti-apartheid struggles, Vietnam War protests internationally, and a radical emergent youth culture,” says Kasrils.

Generations of schoolboys from KES and other South African schools were subjected to the same cold-blooded treatment until corporal punishment in schools was banned in 1997. Apart from the physical pain, the vivid detail with which these experiences are recalled reveals something of the psychological and emotional imprint that remained.

Derek Hewitt from the class of 1970 was caned by the headmaster at the time, Roy Corbett, aka Mango or “The Boss”:

“I saw Corbett retreat to the end of the carpet, turn and apparently paw the carpet like a raging bull… The second stroke was, if anything, worse than the first. Through my pain, I heard Mango give an animal snort, then his footsteps pounded the carpet again, and I swear he left the ground as he flailed with full force at my tight trousers… By the time the fourth cut landed, I was gliding into an out-of-body experience.”

Kasrils describes his experience of being caned in the 1950s by then principal St John B Nitch in his book Catching Tadpoles – The Shaping of a Young Rebel**:

“I was like a trapped animal in a forest, all my senses geared to his movement, my ears sensitive to the opening of a cupboard and the swishing back and forth of his cane, as, like an executioner, he psyched himself up for the assault… I made the error of turning around, wondering where on earth he had got to, just as he sprang at me, cane raised above his shoulder ready to descend … muttering through his teeth, ‘Buck down’ … I bucked down obediently, bracing myself for the inevitable, teeth clenched, as I received another fierce blow which pitched me into the black void…”

Sadistic caning – sometimes flogging – was widespread in the school, with different teachers developing distinctive rituals. An Afrikaans teacher known as “Blob”, for instance, kept multiple instruments of torture – Kweperlats – stored above his cupboard, a single black glove reserved for canings, and drawing pins stuck to the floor indicating where he should place his feet and where his victim should stand beneath his platform for lashes to achieve the greatest impact. He caned a new boy brought to the class a little late, who had just arrived from another school, for being late.

“The infractions which resulted in caning were many – or none,” Hewitt writes. “As a result, every boy at school maintained a high level of vigilance, like impala carefully approaching a waterhole, because one never knew when the stick might strike or for what reason.” This officially sanctioned punishment happened everywhere: behind closed doors or out in the open, in classrooms, in the principal’s office, on the sports fields, in dormitories and in prefects’ rooms.

“Corporal punishment is outlawed, yet we are continually jarred by a colonial legacy within our education system, as shocking episodes of racism come to light in schools around the country,” Kasrils says. The culture of violence, according to Kasrils, has “bled into our South Africa today”. We see it in police brutality, in the prison system, in the attitudes of political leaders who condone the violence. It is not just apartheid cruelty that has been carried forward; what happened in colonial times marks us to this day, he says.

The so-called “Milner schools” – Pretoria Boys High, Potchefstroom High School for Boys, Parktown Boys’ High, Jeppe High School for Boys, Pretoria High School for Girls, and Johannesburg High (King Edward VII School) were rooted in this culture of violence.

A portrait photograph of Edward VII after whom the school is named. (Image: Wikimedia)

In 1918, the Union Jack was hoisted at the back of the school hall, Haynes writes, and it remained there for 40 years. On the wall at the front of the hall, behind the podium, a vast painting of King Edward VII occupies pride of place to this day. Dressed in full military regalia, sword in hand, he looms large as the backdrop to the headmaster’s daily address to the school.

“Nobody told us about this king and we never asked. It was not relevant to anything we learnt at school, in history or anywhere else. All we knew was that he was a King of England, that’s as far as it went. And we were proud to be part of a bigger thing, like a King. I mean Pretoria Boys High was just Pretoria Boys High, Potchefstroom Boys High was just Potchefstroom Boys High but we were King Edward.”

Haynes’ knowledge of King Edward VII grew while he was working on the book. He uncovered a smutty reprobate known as “Dirty Bertie”. “I mean Prince Andrew has got absolutely nothing on this guy,” Haynes says.

Why was Johannesburg High renamed King Edward VII School for Boys? It all goes back to the first headmaster, a man named Desmond Davis, who lobbied for the school to be renamed in honour of King Edward VII. Even Lord Milner, with his blatant agenda to ensure that English-speaking government schools would continue to produce boys and girls who would perpetuate colonial rule, had more tact than to give the schools British names, given the intense antagonism between the British and the Boers in the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer war.

This antagonism between Johannesburg and Pretoria, between the moneyed, predominantly English-speaking Randlord territory and the apartheid regime’s political headquarters in Pretoria, simmered underground, occasionally surfacing like a suppurating wound.

A clash between these two very different South African cultures is described in the book. Towards the end of 1970, not long after music icons Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin died, the Milner Park Pop Festival (South Africa’s answer to Woodstock) was held on Kruger Day. The oppressive climate in South Africa at this time is difficult to describe, Hewitt writes. “Under John Vorster, the conservative grip on the creative throat of the country was tightening. Our rulers regarded long hair as evil, atheistic, and a sign of Communist sympathies… They saw flower power, free love, rock ’n roll and all the other manifestations of the youth movement as a Communist plot.”

At around midnight a group of Tukkies (Pretoria University) students invaded the stadium. They had filed a complaint with the Minister of the Interior, objecting to the scandal of holding a pop concert on Kruger Day, which was accepted, but since the concert was not banned, they were intent on teaching the renegades a lesson by chopping off their hair (long hair was part of the Communist plot). Whooping with glee, they bundled a number of music fans into vans and careered off into the night, with loud threats to cut off their hostages’ locks in a public shaming ceremony in Pretoria. The incident received considerable media interest.

KES boys were militarised in the British tradition through the cadet system, introduced in 1906, which was essentially about equipping South African boys to fight for and defend the British colony. KES sent more boys to fight for the British in World War 1 and World War 2 than any other school in the world, and their contribution (250 died) is commemorated to this day on the school cenotaph. The school still boasts a Pipe Band in full regalia – kilt and sporran, spats and boned shoes – only these days it is racially integrated.

“The bagpipe band has remained a central feature of KES since its formation in 1950 under the 1st Transvaal Scottish Regiment,” Haynes says. “I went to the KES Golf Day. At the end of the day, out comes the guy to play the bagpipes and he is black… Since I was at the school, the victims of the SS Mendi have been added to those who are commemorated.”

Despite the incongruities, KES seems to be holding up, even thriving, Haynes says. The demographic has changed and there are now 21st-century formal procedures in place to run every aspect of the school.

“As I read this book,” Kasrils says. “I wonder at the absurdity of the name. At its establishment in 1902, the place was known as the Johannesburg High School. When a new monarch ascended the British throne there was a name change in his honour in 1910, the singular brainchild of the headmaster, an avowed monarchist. The eponymous King Edward had more in connection with debauchery than education. Would it be too much to suggest they kept abreast with the times and renamed it after Nelson Mandela or Gauteng?” DM

* Copies of the 500-page book, which covers all aspects of school life from the mid-sixties to 1970, are available from Tim Haynes at [email protected].

** Catching Tadpoles – The Shaping of a Young Rebel (Jacana Media) is obtainable from Exclusive Books.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

KES and TELL is the story of the school, and the experiences of its cohort in 1970, that is 50 years ago. It is situated in a historical context that does not exist anymore. Besides the school having it’s same location, it is barely recognisable such has been it’s development.

It’s demographic has changed in line with post 1994 norms, as has the modernisation of it’s school management systems. For these changes the school must be acknowledged, for through these difficult times it has held up, in fact thrived and is a leader in the pack in terms of doing what has been necessary. Yes it is not perfect, and yes it still has some way to go in terms of some relics of the past. But if anything, the KES and TELL book stands as a compliment to just how far it has come. Tim Haynes …….RSA editor.

And then, once you have read this, read Marguerite Poland’s Iron Love, then watch the movie, Moffie – even although the film is is not 100% correct in its detail – and I reckon a very clear idea of what most South African men had to endure growing up in the 70s and 80s comes into clear view. The fact that so many survived and more didn’t commit suicide or land up in mental institutions is truly a miracle.

I remember the KES boys from my 50s and 60s childhood, at the bus stop in the full heat of summer, in full uniform, blazer, tie, socks, lace-ups. It seemed unhealthy, another colonial legacy.

There’s nothing like school day memories, especially when they’re put in context, as this tantalising article shows. Perhaps the book should be recommended reading for would be educators?