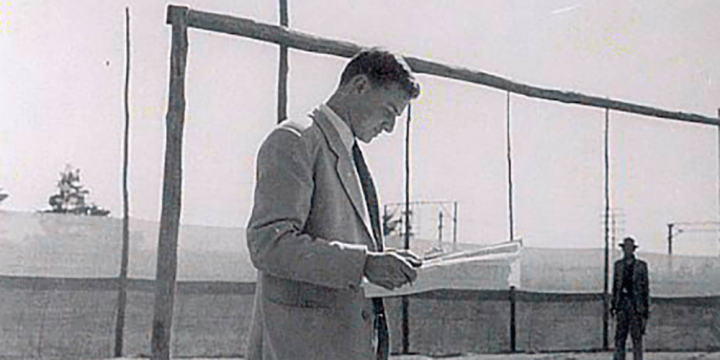

CLIVE MICHAEL CHIPKIN (1929-2021)

South Africa loses a cultural, social and historical icon of Johannesburg

Clive Chipkin’s most enduring contribution to South African architecture was in the interpretation of his city in his writing. He loved Johannesburg, but was not nostalgic or maudlin as the city changed, declined and new residents from all over Africa arrived. That was part of the natural order of things.

Clive Chipkin died peacefully on 10 January 2021 in Johannesburg, aged 91. Clive was born on 21 March 1929 in Johannesburg, the city he made his own. He was an extraordinary person who lived a rich and full life. Clive was passionate about Johannesburg.

In 2013, his alma mater, the University of the Witwatersrand, recognised his scholarship with the award of an Honorary PhD. His books Johannesburg Style: Architecture and Society 1880s to 1960s (David Philip, Cape Town, 1993) and Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950 (STE Publishers, 2009) are seminal monographs which made his name. They represent a lifetime of research, extraordinary knowledge and critical analysis.

Johannesburg Style quickly achieved iconic status and is regarded as a work of great distinction. Eric Itzkin describes it as a work of genius. The title, Johannesburg Style, was meant to signify that Johannesburg has a characteristic way of doing things. Clive dissected how the colonial capitalist city with an entrepreneurial culture evolved – this was the unique style of Johannesburg.

The two Chipkin Johannesburg volumes give an understanding of the making and shaping of the city of Johannesburg and its cultural, social and historical underpinnings. They show a remarkable breadth of knowledge and the capacity to pose difficult questions about the roots of design and the shaping of architectural styles and fashions. How did international styles come to the city? For example, why and how did Brazilian architecture come to Hillbrow? These works are authoritative and commanding. Together they have set a high standard of serious scholarship in the study of architectural history in Johannesburg.

They are groundbreaking in that no other work on the subject of Johannesburg’ architecture comes close to matching Clive’s reach across so many disciplines. Both books are essential works of reference for anyone interested in Johannesburg’s history and change.

These massive books are treasures and now highly collectable. What Nicolas Pevsner of HJ Dyos is to London, Chipkin is to Johannesburg.

His lens is architectural history, but his breadth of scholarship is such that he enables the reader to see the city and its buildings with a fresh understanding about why certain styles were adopted in particular periods and why the city has been rebuilt through successive waves of capitalist expansion. Clive was particularly enthusiastic about Modernist architecture in Johannesburg because he was a product of the flowering and nurturing of those ideas at Wits in the 1940s.

The site of study is Johannesburg, but the analysis of how and why a mining camp founded in the 19th century and grew into a sprawling African metropolis and magnet for settlement is of international importance. Clive drew on a rich and diverse array of sources across architecture, politics, economics, sociology and history to explain the development of the city through 120 years, meticulously collected, annotated, indexed and filed in a huge personal archive. They are a treasure trove of photographs of a city that capture perpetual change. Clive also added some of his own meticulous drawings.

Clive grew up in Yeoville and was educated at King Edward VII boys’ school – which he saw as Edwardian in architecture, ethos and education. He was proud of his old school and it was a strand in his embarking on understanding how the imperial culture played out in Johannesburg as the town shifted from a temporary camp that drew adventurers from all over the world to being a permanent town with its first steel-framed buildings and first lifts, like the third Corner House and Victory House or the Carlton Hotel, or indeed his very Edwardian school.

Clive studied architecture at Wits in the late 1940s and became excited by the modern movement and a completely new approach to office blocks, skyscrapers and homes. Clive’s son Ivor described him as “a Fifties man” full of the optimistic ideal of a better society, fair to all. Clive wanted architects to deliver on the dream of a better society.

Clive knew his city because he was a practising architect; he initially gained experience as a young man working on a building site and then working for the architects, first Bernard Janks and later Wayburne and Wayburne, where he connected with other architects who had a socialist take on politics and pushed (at that time without success) in challenging the growing power of the emerging apartheid state.

Clive Chipkin’s most enduring contribution to South African architecture was in the interpretation of his city in his writing. He loved Johannesburg, but was not nostalgic or maudlin as the city changed, declined and new residents from all over Africa arrived. That was part of the natural order of things.

He made friends with Alan Lipman and Rusty Bernstein. Bernstein and Bram Fischer helped draft the Freedom Charter. Clive remembered 1955 as the year of the Congress of the People in Kliptown. In a self-deprecating way that was so typically Clive, he recalled that his finest architectural contribution for this event was his design of the toilet facilities.

Clive earned his B Arch degree at Wits in 1954 and as a single man he set out to explore the world. He gained experience working for the old London County Council. It was a fairly short stay in London followed by a not-so-grand tour of Europe — Clive hitch-hiked but it was an 18th-century tradition to explore the art and architecture of the continent. Clive went to India and encountered Lutyens and Baker’s imperial ideas in their grand designs in New Delhi.

Back in South Africa, these influences led Clive to be interested in the Baker-Lutyens visible imprint on the Union buildings, Parktown grandeur, the Johannesburg Art Gallery and the Rand Regiments Memorial. Clive was also interested in Le Corbusier’s ideas for a modernist metropolis at Chandigarh. This was all background to how Chipkin began to study and observe Johannesburg.

He established his own practice in 1958; it was a small office he described as “an overworked and underpaid practice”. Over time he worked as an association with firms such as Trident Steel and then Cape Gate and with Jeff Stacey designed a series of industrial buildings at the Vanderbijl plant of Cape Gate. These buildings were considered to be progressive, the architects delivered on two goals for the client, Mendel Kaplan — quality and optimism.

Clive considered the Central Facilities building to be a “little masterpiece” as the objective of the collaborative architectural team was to introduce coherent pedestrian routes, street architecture and human scale to counteract the hostile vistas of an industrial complex. Clive wrote extensively about the project in Johannesburg Transition and was proud of the designs and how architecture could contribute to better industrial relations.

Clive was a man who lived his values and in 1986 was a founding member of the group “Architects Against Apartheid” an informal pressure group that included architects such as Chipkin, Hans Schirmacher, Henry Paine, Ivan Schlapobersky, and Lindsay Bremner. They tried to make colleagues aware of how the gross application of apartheid ideology to architecture was distorting the moral and ethical basis of the profession in South Africa. They argued that it was unethical to participate professionally in the design and planning of apartheid buildings.

Clive Chipkin’s most enduring contribution to South African architecture was in the interpretation of his city in his writing. He loved Johannesburg, but was not nostalgic or maudlin as the city changed, declined and new residents from all over Africa arrived. That was part of the natural order of things.

Clive contributed to more than 50 publications, including his two monographs, starting with articles about architecture in India. His books on Johannesburg brought his thinking and reflections together. Clive worked closely with his wife of more than 50 years, Valerie Francis Chipkin, who was his editor and who shaped his archives. Clive was awarded an Honorary D Arch Degree by the University of the Witwatersrand in 2013 and in 2015 gave his archive to the School of Architecture and Planning at Wits. The archive was named for his wife.

Clive died far too young because he read, studied and wrote about architecture until the end of his life. He was a fun person to be with, embracing his city on tours and trips of exploration. He drew maps of the route to give the best view of the Witwatersrand Ridges. Clive gave readily of his knowledge in lectures, interviews and tours, but he was always so self-effacing, modest. He was a caring person who gave to everyone he encountered. At the time of his death, he had completed the third volume, Johannesburg Diversity. It is heading towards publication. Clive is survived by his three children, Peter, Lesley and Ivor, four grandchildren and his close friend Marcia Leveson. DM

Kathy Munro is Associate Professor, School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand. Wits University, heritage author and researcher.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A full life well lived. Our condolences to his family and other colleagues who will miss him.