OP-ED

Reflections of a Wayward Boy: Into exile, and the streets of London

When, following further arrests in South Africa in 1965, I decided to go into exile, I had no intention of going any further than Zambia or Tanzania. Naïvely, I saw myself joining the ANC army in exile and returning within five years as apartheid crumbled. Instead, I was ordered out of Zambia ‘for his own personal safety’, granted political asylum in England and ended the year as a student activist in London.

On Saturday morning, 28 August 1965 I was already packed and ready to leave Zambia in a hurry, my bush hat handy at the top of my rucksack. Although then-president Kenneth Kaunda had said my personal safety was at risk and had applied to countries further from South Africa to give me asylum, there had been no response. That meant the immigration authorities would cart me off, as an illegal immigrant, to a detention centre on Sunday morning.

But I had no intention of being detained. I planned to disappear northwards to Tanzania that Saturday night, bearing an American passport lent to me by Lenny Levitt, a Peace Corps volunteer I had befriended. Lenny, who was a good 5cm shorter, and bore no resemblance to me apart from a fair complexion, assured me it would not matter. “You know, they just look at the date and stamp it,” he said. When I tried to contact Lenny, who is well known in the United States as a journalist and crime writer, for permission to mention his passport gift of 55 years ago, I discovered that he had died in Connecticut in May 2020.

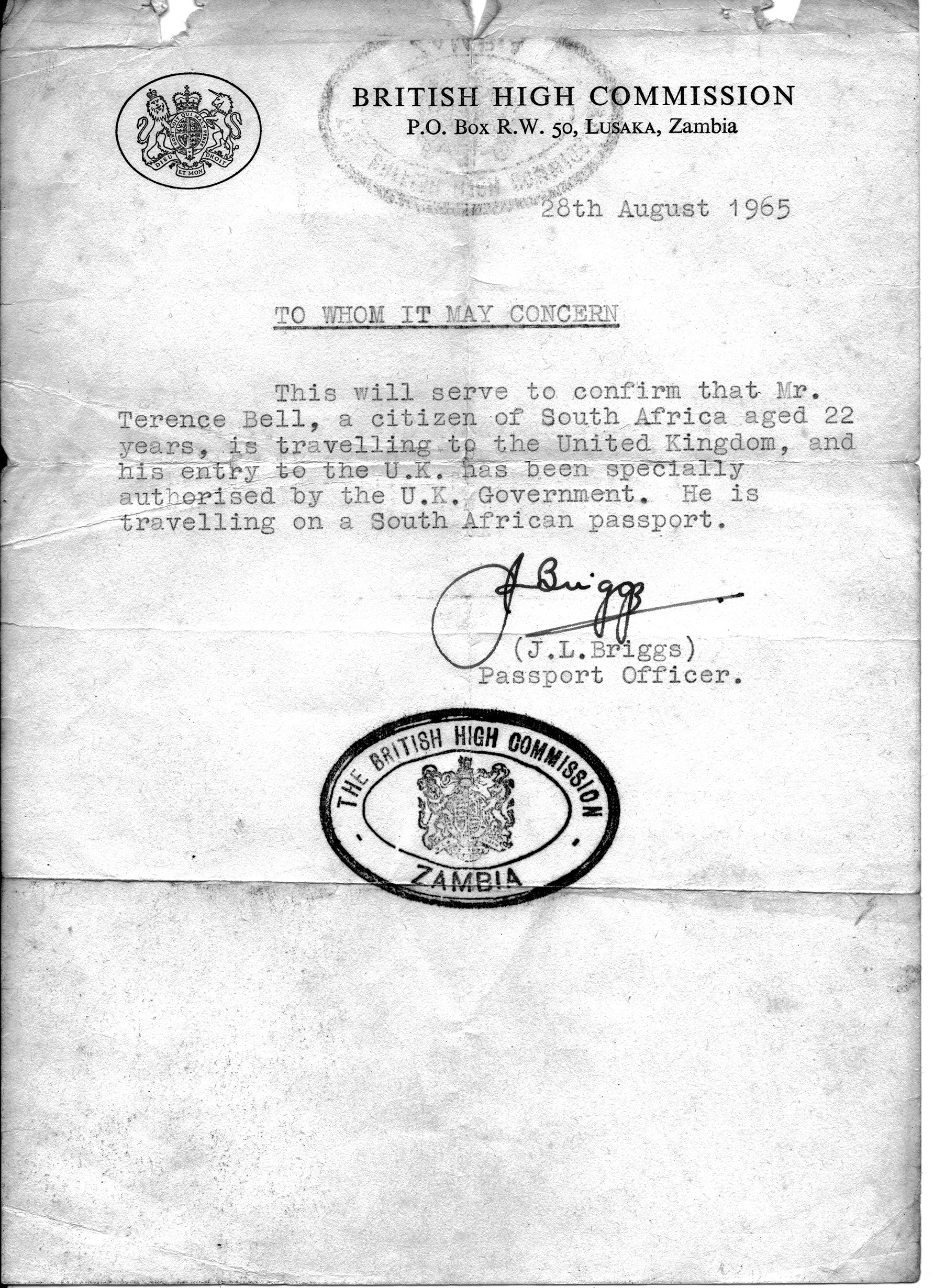

However, I never had to use that passport: on the Saturday morning, a telegram arrived from the British high commissioner to Zambia advising me that his government had granted me political asylum. I should be on a flight from Lusaka to London departing in a matter of hours. Times of Zambia editor Dick Hall quickly typed out a letter of introduction to his friend, Derek Ingram, assistant editor of the Daily Mail in London and photographer Ralph Krag Olsen turned up in the fastest vehicle available, a Mark 10 Jaguar. At mostly 100 miles (160km) an hour, we covered the near 300km (186 miles) in two hours.

At the airport, a high commission official handed me a single slip of paper that was to be my passport into England. Although it said I was “travelling on a South African passport”, this was all I had since the Zambians had never returned my phoney travel document. And there was barely time to say goodbye to a group of colleagues and friends before boarding the BOAC VC-10, the first jet passenger aircraft that flew twice weekly from Lusaka to London.

(Image: Supplied)

I had never travelled before in an aircraft, let alone a jet. And there were no 11-hour direct flights then. Passengers were allowed to disembark briefly in Nairobi and Khartoum, although not in Rome, before reaching the British capital. That, and the adrenaline of the moment, meant that I never slept and, courtesy of a tailwind, we landed in London at 6:30 in the morning instead of the scheduled 8 o’clock. As a result, as I later discovered, there was near apoplexy in the Home Office and, as I found out only 30 years later, I missed a welcoming party led by Margaret Legum who had campaigned in England on my behalf.

Outside the airport, I boarded a bus, got to Victoria Station in central London, walked aimlessly for an hour or more and then took a taxi that dropped me off at the YMCA in Tottenham Court Road. There I joined a queue of young travellers waiting to be booked in after 10am.

Before midday, I was shown a room on the top floor and sat down on the bed. When I woke it was dark, nearly 9 o’clock. I had slept through my first day in London. But, looking out of the window I spotted, down below and across the street, the Blue Posts Charrington pub. At least I could experience something typically English. In the pub, I mimicked what I had heard and seen in English films I ordered: ’alf a pint. This I struggled to finish, ending on the spot any future relationship with English beer.

The next morning I turned to the telephone directory to try to make contact with other exiles. The most prominent name that came to mind was Slovo. And there it was. I dialled the number and asked for Joe Slovo. But the Slovos no longer lived there. A man with an Irish accent informed me that the house was occupied by a “collective” of squatters. “If you’re looking for a place to stay, you’re welcome here,” he said, giving me directions to the “squat”. And there I based myself for the next two or three days, completely unaware that I had caused major problems at the Home Office because I had apparently “disappeared”.

But in that time I made contact with other exiles and was directed to one who owned several houses and had a furnished room to rent. It was in Clapham, south of the Thames and was cheap, so I took it without seeing it and paid a week’s rent in advance. However, on the day I moved in I decided I would leave at the end of the week. Quite apart from the sagging mattress and the dusty, threadbare carpet, I wasn’t prepared to share one bathroom with nine other residents.

At least I had an address, so I donned my suit and tie, saw Derek Ingram and landed a job with an investigative team on the Daily Mail. But before I could start work, I was told I needed an alien registration document available from the Home Office centre in Croydon. It was then that I discovered, from an obviously irate official, that I was officially a missing person; that police and other agencies had been notified that I had disappeared. But I got my document, started work and found alternative accommodation, sharing a flat with one other person and for the same rent.

Money wasn’t a problem. The basic Fleet Street wage for journalists was more than twice the average railway worker’s pay of £10 a week. And while we on the Daily Mail all earned the same basic wage, it was a far from egalitarian set-up. Because everybody who started work as a journalist got a tax-free “expenses” payment. It started at £5 a week and it was said that some “top scribes” received up to £50 a week in “exes”. This scam lasted for years until the Inland Revenue finally put a stop to it. We reporters also never used to hang around the newsroom; instead, we gathered in the “Mucky Duck” as the White Swan pub on the ground floor of the Mail building was known. There was a direct telephone link to the news editor’s desk, to summon anyone was needed.

Exciting as it was, I had by then also linked up with what became, contrary to official policy, a youth group made up across the ethnic spectrum as the London ANC Youth. And Ethel de Keyser of the Anti-Apartheid Movement agreed that I should edit a planned monthly tabloid, Anti-Apartheid News. It was the start of perhaps one of the most intense times of political involvement: the Vietnam war was underway and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was rallying hundreds of thousands at protests, while Rhodesia and the links with apartheid South Africa were becoming major news and protest features.

It was then that Aziz Pahad, later to become the longest-serving deputy foreign minister in the post-apartheid era, told me about UN fellowships to university. He was applying to University College London (UCL) for the international law-based diploma in international affairs. “After apartheid, we are going to need diplomats,” he said.

I applied, was accepted, and was awarded a UN fellowship that paid me, tax-free, almost exactly the basic Daily Mail wage, along with a $200 annual “book allowance”. So, shortly after my 23rd birthday, I resigned from the Mail to become a newly minted student activist. As such, I founded the shortly lived International Relations Student Group to protest Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence — and experienced my first arrest in England. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.