First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

The world’s need for numerous Covid-19 vaccines

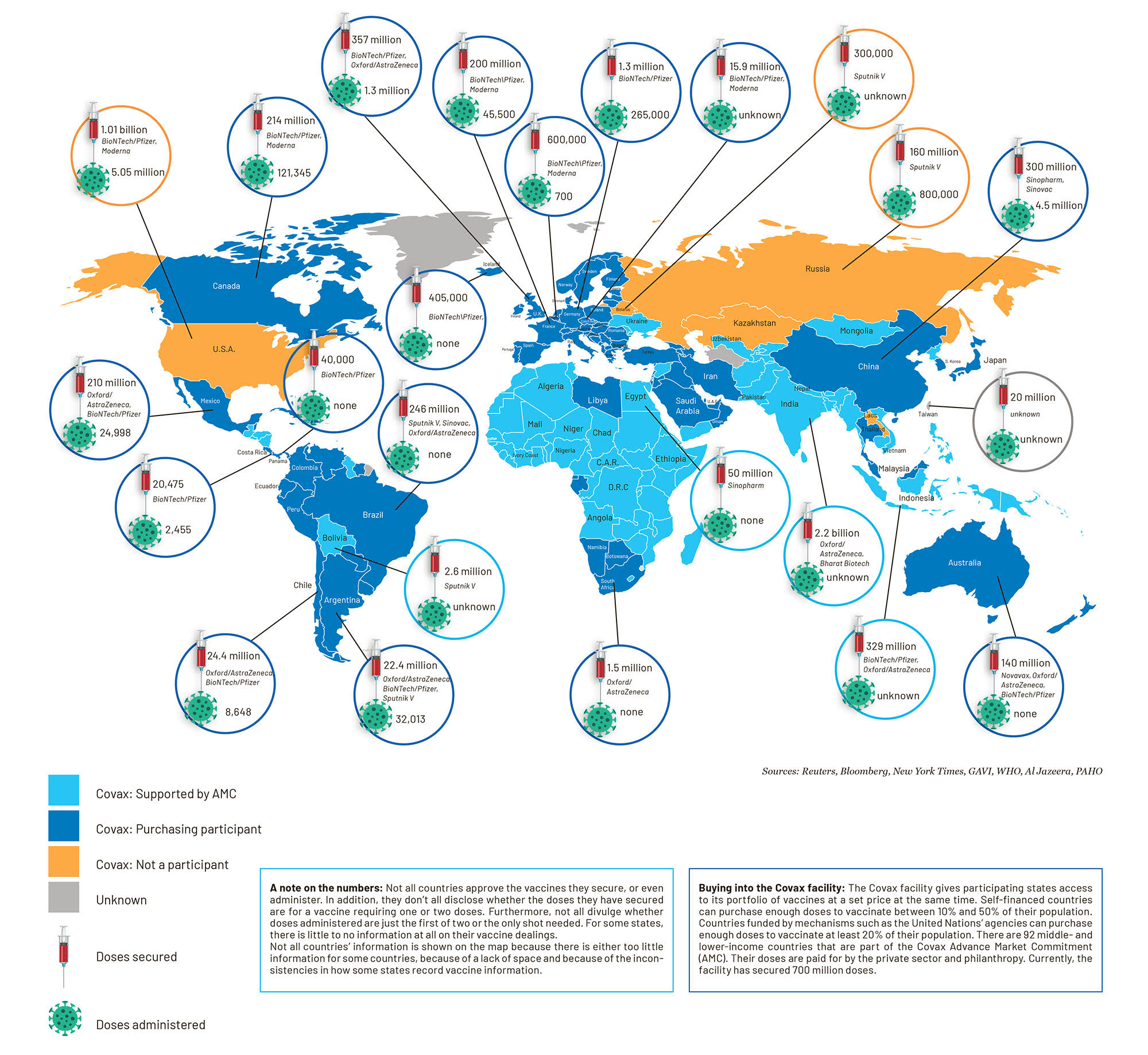

Out of the hundreds of Covid-19 vaccine candidates, seven have already been given approval for general use or authorised for emergency use. And all of the world’s countries want their fair share of them. Already, more than 8.25 billion doses have been bought up and some 15 million doses have been injected across 37 countries. These seven vaccines have the same effect, but work differently in the body and require their own means of transport, storage and administration. And at each stage the entire enterprise could collapse.

What is it that vaccines do in the body?

Vaccines may vary in their makeup, manufacturing and storage, but they all prepare the body to annihilate Covid-19 before it even encounters it. Vaccines assist the body’s own natural defence against disease: the immune system’s strength and its ability to remember past confrontations with a disease.

When the immune system first encounters a pathogen (a virus, bacteria or other micro-organism that causes disease) it produces antibodies. The antibody’s task is to eliminate a specific antigen – the part of the pathogen that causes sickness. However, the production of antibodies takes time.

A vaccine familiarises the immune system with how to produce these antibodies ahead of encountering the virus. A vaccine consists of a minute, weakened and non-dangerous version of the pathogen that causes disease. The vaccine provokes an immune response without the antigen being present. This way, the immune system can understand how to produce the specific antibodies ahead of encountering the antigen and can react more swiftly.

In addition, it produces “memory cells” that can recollect this antibody recipe. When the immune system encounters the antigen again, its reaction time will be much quicker.

What are the different types of vaccines being used against Covid-19?

The vaccines that have been either approved or authorised for early use against Covid-19 use one of four different technologies:

Nucleic acid/genetic vaccines

These vaccines use synthetic virus genes to trigger an immune response.

The vaccine does not alter the genes of the vaccine recipient in any way. The genetic material causes the body’s cells to produce the antigen. This in turn stimulates the production of antibodies. The immune protection lasts a long time, but the genetic instructions combust within a few days. The vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna use this technology.

Viral vector-based vaccines

These vaccines also provide the body’s cells with genetic instructions; however, the vehicle is different. Instead of genetic material, this vaccine uses a harmless virus to transport the instructions. The body’s cells produce the antigen, which triggers antibody production. The vaccine for Ebola makes use of this technology. The Covid-19 vaccine made by AstraZeneca and Oxford University, as well as the Gamaleya Research Institute’s Sputnik V vaccine, use this technology.

Inactivated vaccines

These vaccines contain viruses whose genetic material has been destroyed. However, they can still provoke an immune response. This technology is used in the vaccines for measles, mumps and influenza, among others. The only approved Covid-19 vaccine using this technology is one by Sinopharm and the Beijing Institute of Biological Products.

Protein-based vaccines

These vaccines contain either fragments of or entire virus proteins. Some might be attached to tiny particles. This triggers an immune response. The hepatitis B vaccine uses this technology. A protein-based vaccine for Covid-19 is yet to be approved, but potential vaccines produced by Novavax, Sanofi and Bektop use this technology.

We have some vaccines – now what?

The search for Covid-19 vaccines has been “phenomenally successful”, considering that usually only about 10% of vaccine candidates are eventually licensed, according to Professor Shabir Madhi.

He is a professor of vaccinology at the University of the Witwatersrand and the director of the South African Medical Research Council: Vaccine and Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit.

Recently, he has led the South African leg of the Novavax Covid-19 trial and the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine Covid-19 vaccine trial.

However, each vaccine faces four “valleys of death”, he explains. The first is getting licensed. The second is scaling up manufacturing to meet global demand – this is where it is at, right now.

The third is affordability and access. The fourth is the implementation of an immunisation programme.

“To some extent that becomes the biggest challenge of all in terms of the public health value of vaccines materialising,” he explains. “You can have the greatest vaccine but if you can’t eventually get people immunised then those vaccines count for very little.”

Why try to gather different vaccines?

The point of sourcing approved Covid-19 vaccines from different companies is so that more vaccines can be administered over a shorter period of time.

Madhi explains: “Unfortunately, at this point in time it is extremely unlikely that we will successfully get the number of vaccines we require from a single supplier.

“[Most] of the vaccines that will be produced over the next six months [are] pretty much spoken for because of the AMC, which SA did not engage in early enough. That’s where we are.”

In addition, a country needs to have the infrastructure to realistically deploy a vaccine – whether that’s cold storage or the ability to administer two doses of a vaccine weeks apart. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for free to Pick n Pay Smart Shoppers at these Pick n Pay stores.

Graphic: Jocelyn Adamson and Christi Nortier

Graphic: Jocelyn Adamson and Christi Nortier