BOOK REVIEW

When the matrix shifts: Death and the After Parties

Joanne Hichens’ Death and the After Parties is a story about what happens when we lose someone we love and we’re broken beyond repair.

Two weeks into lockdown, my Dad took ill. A month later, he was dead. In the months that followed, I spiralled into a dark pit of nothingness. Consumed by loss, I journeyed into the underworld, my only solace being stories about death. This is how I came across Joanne Hichens’ Death and the After Parties – a story about what happens when the matrix shifts – when we lose someone we love and we’re broken beyond repair.

Hichens writes, ‘How do we keep in mind how fast time diminishes for us, that the years left become a smaller and smaller percentage of time compared to what we have already lived?’

This is at the heart of the book – the fact that time is a narrow bandwidth. We live. We love. We lose loved ones.

Hichens tells her story in a register that has depth in its insight, in a way that glistens with humour. She tells how her mother took ill with cancer in 2010 and passed away shortly after. Four years later, her husband, Robert, woke up one morning thinking he had indigestion. Hichens googled his symptoms and insisted on taking him to hospital. They drove to Constantiaberg Mediclinic. Her husband thought that it was unnecessary. At the hospital, Hichens dropped him at the entrance and went to park the car. By the time she got to the waiting room and was standing around reading the notices on the wall, her husband had had a fatal heart attack. Four months later, while she was still in the throes of trying to process his death, her Dad became terminally ill. It is the magnitude of this collective loss that drove the book.

‘I would write haphazard diaries, and writing about death became part of it,’ she says. ‘If you are writing every day, your body is in a habit and this did not stop for me after my husband died. I found it comforting.’

But Death and the After Parties did not start out as a memoir on grief. Initially, Hichens was working on a PhD on loss in the city.

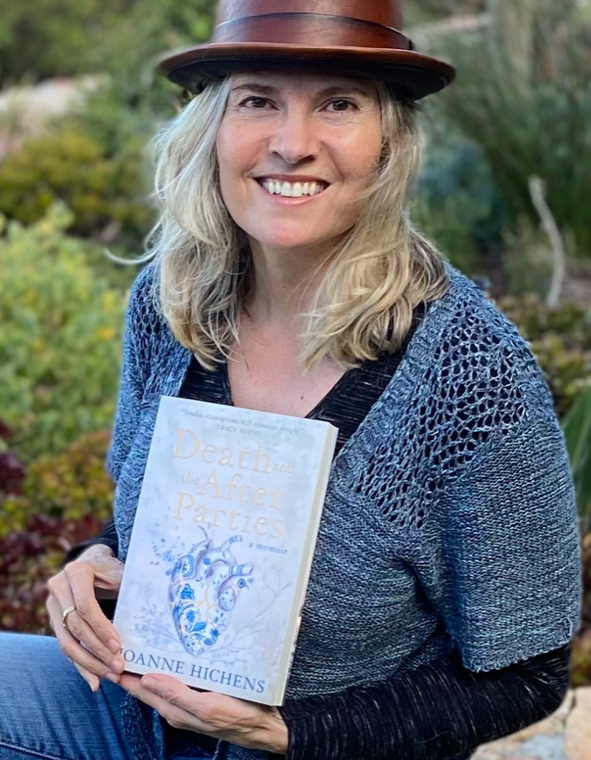

Joanne Hichens (Image courtesy of the author)

‘I wanted to explore Cape Town as a damaged place. So many people here have experienced loss in so many ways – the loss of dignity, land and ownership,’ says Hichens.

When her own loss became so palpable, the narrative shifted shape into something more personal – interweaving moments of personal loss with a reflection on a broader, societal loss. And this is part of the magic of the book – like a blurred picture where the axles slowly come into focus, we see Cape Town in its complexity – its beauty interwoven with its torment. We catch glimpses into its layered politics and socioeconomic issues, the discrepancy between the haves and the have-nots, the violence and poverty. The theme of loss in the city entwines with Hichens’ personal loss, the two layers of the story dovetailing each other in a poignant symbiosis.

Death and the After Parties is a story about how we cope when a loved one dies. But it’s so much more than that. On the one hand, it exposes the rawness of the day-to-day moments. Confronting the artefacts of the dead – their clothes, toothbrushes, the books they loved.

‘I’d see my husband’s things and it would hit with unbearable clarity that I would never see him again,’ Hichens says. ‘Through my tears, I’d write, where are you?’

But Death and the After Parties also takes a step beyond the mourning of a person – it becomes a portal into mourning something bigger and far less tangible – the loss of a family unit, of a sense of belonging to something, the loss of a childhood, the history of who we once were. This is beautifully expressed when Hichens writes about her Dad’s furniture, artwork and other belongings going on sale. The ‘textured backdrop’ of her parents’ lives are lined up and dispatched. This ‘undoing of a collection’, with reference to Edmund De Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes, becomes a metaphor for the disintegration of things that once were whole. It’s the search for the moments in time, before the ‘undoing,’ that propels the memoir.

‘After my Dad died, I started having more vivid memories of my childhood, I found myself pulled into that remembered experience and had to write to it,’ says Hichens.

Hichens takes us on a trip of her childhood as a daughter to a diplomat father, travelling the world. It is the time of the darkest moments in apartheid history, the student protests in Soweto in 1976, the State of Emergency in the ’80s. Hichens brings all of this under her lens, with razor-sharp honesty. She writes about her father’s official car being pelted with tomatoes in New Zealand, how his face is put on a poster with the words, ‘Wanted for crimes against humanity’.

‘In writing the book, I was able to look at how deeply damaged I was by my past, how the burden of being on the wrong side distorted my sense of self-worth,’ says Hichens.

This sense of how we are shaped and moulded by our past, how we carry it into our future and how we stare at its ghost when we lose a loved one, is a recurring theme in the book. The past leaves an indelible mark. We are compelled to put it under the microscope when someone close to us dies.

The book phrases this acutely, ‘I am reminded that each of us is merely an adjunct, as those in the future will be, for a short time, to the people and the history that has gone before.’

Part of the process of connecting the dots between lost loved ones and our history invariably involves a descent into a darkness of sorts. And this is the biggest strength of Death and the After Parties. Hichens is brutally honest in describing her own descent.

‘I spill my mess again and again,’ she writes.

And we are allowed in, as spectators, to the enormity of her grief – the ways in which she tries to numb it and the toll it takes on her. We walk with her as she is drawn to graveyard excursions, photographing gravestones and memorials along the side of the road. We’re there as she murmurs the names on gravestones, wondering about their lives. We journey with her to a Death Café (yes, there is such a thing…), to meet with others who have experienced loss. We laugh with her when she discovers that the best thing about the Death Café is the two slices of chocolate cake that she devours at teatime.

As it should, Death and the After Parties moves on to how life goes on after loss. We fall. We break. We pick up the pieces and hobble along. Life is short, and we must celebrate the moments of bliss.

The book sums this up succinctly, ‘We are here for a mere speck of time, we momentarily disrupt the silence with hurly-burly, a short-lived exuberance, in the ignorant bliss of living.’

When we read a book, it is the reader who breathes life into the words. Each of us takes away from a book that which most has meaning for us. When I put my ear to the page of Death and the After Parties, I hear not just a story of inexplicable sadness, but one of hope. A story about the beauty in living, even as we are all in the process of dying. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.