BOOK REVIEW

Shuggie and Agnes Bain — two newborns on the pantheon of the great characters of world literature

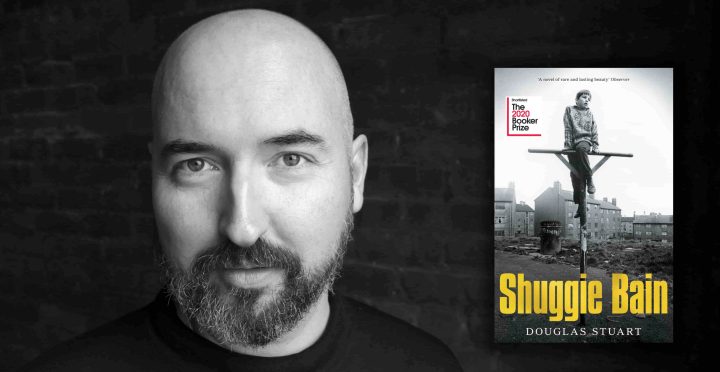

‘I am always looking for tenderness in the hardest places.’ — Douglas Stuart, winner of 2020 Booker prize

The writer Elif Shafak swears by stories. She believes they are the key to our remaking, a buttress against “numbness”, a bridge to our reconnection as human beings. In her recent book, How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division, she writes how “we are made of stories”. As a novelist, she expresses her preference to “dig into ‘the periphery’ rather than ‘the centre’ and focus my attention on the marginalised, underserved, disenfranchised and censored voices. Taboos too, including political, cultural, gender taboos. There is a part of me that wants to understand, at any moment in time, where in a society the silent letters are hidden.”

2020 Booker Prize-winning novel, Shuggie Bain, by first-time novelist Douglas Stuart, ought to tick all Shafak’s boxes. It did the Booker judges’ panel which described it “as a longterm classic that will be loved, admired and remembered for a very long time”.

It ticked all mine too.

Shuggie Bain is a straightforward story, but at the same time a book of many layers, many themes and a long list of large-as-real-life characters. All merit discussion. But stripped to its core it is the story of a working-class Glaswegian boy growing up in the 1980s and the unbreakable love he has for his mother, Agnes, who suffers from alcohol addiction… triple blended with hope. It is a child-like love, that at an early age often inverts, but never subverts the traditional parent-child relationship of care. That is, he cares; she cares depending on her state of inebriation.

In our world, there are millions of parents who suffer the disease of alcoholism, but they are never elevated to leading roles in great works of fiction. There are also millions of children of alcoholics, like Shuggie, but they are not seen as the stuff of tragedy or epic.

That is why it is remarkable how Shuggie Bain gives us a window on their lives, cries and resilience.

George Orwell might have called this story “how the poor live”; Elif Shafak, “how many people survive — and don’t — in an age of dispossession”. It has a deep, surprising and distressing core — but feeding its heart are other layers and stories.

There is Shuggie’s struggle to understand his sexual orientation and gender, in a time, place and class that predated tolerance and understanding. In this world Shuggie, who is introduced to us when he is nine years old, is a “poofy wee bastard”, “Big Bobby Bender” and other denigrating epithets; because he is effeminate and doesn’t fancy girls he is “no right”.

In a particularly poignant moment, Shuggie is asked by Leanne, a girl his age, “Do ye even like lassies?” He answers:

“I don’t know.” It fell out of him unexpectedly, almost like a loose fart, and he regretted it instantly.

But unlike most of his age mates who taunt and torment him for his (presumed) sexual orientation, Leanne — whose mother is also an alcoholic — accepts Shuggie declining her offer to “touch my tits” and admits to not liking boys either.

Their friendship and the wise eyes they acquire over their world becomes one of the few rafts of hope the novel eventually leaves us with.

The brand new ancients of fiction

In her epic poem of the same name, Kae Tempest describes working-class people battered by unemployment and marginalisation as the “brand new ancients” of post-industrial society. I am sure she would celebrate the characters in Shuggie Bain as among them. With its cast of McAvennies, McGintys, McGoverns and Campbells it’s a colourful and busy stage.

Yet the two lead characters of Agnes and Shuggie rise above them to become icons of fiction.

Agnes: Beautiful. Proud. Determined. She is both Shuggie’s storm and his shelter from it. She battles with herself, with the bottle, with her abusive husband and raping lovers, with her envious neighbours, yet never loses her pride or power, not even in the book’s closing scene (of which I will say no more). Her fight with her husband, Big Shug, as she arrives at his home to reclaim Shuggie is classic drama.

By contrast Shuggie: Precious, precocious, proper, breakable. Minutes after the families’ arrival at Pithead, meant to be a new beginning where Agnes gets a house with a front door in return for giving up the booze, he innocently tells his mother in earshot of the neighbours, “We need to talk. I really do not think I can live here. It smells like cabbages and batteries. It’s simply impossible.”

Shuggie. Keen to please, to escape ridicule, but unable to conform to gender norms despite his best efforts. He is old to parts of the world and naive to others.

For me, Shuggie equals some of the great figures of children in English literature such as Pip in Great Expectations or Jo the street sweeper in Bleak House.

‘Fuck the Tories’

Around the Shuggie-Agnes axis revolve other worlds that are in constant motion: the worlds of his brother and sister; his macho taxi-driving Protestant father; his grandparents; the depressed former mining community of Pithead on the edges of Glasgow and bleak working-class housing estates, like Sighthill, at the centre of its inner city.

All are part of a human society in an unjust transition it doesn’t want or understand, driven by economic and political forces who are offstage; the working class, traditionally the majority of industrial societies, are slowly becoming marginal, as the economic policies introduced by the Tories in the 1980s suck the soul out of millions of lives. Working-class people are collateral damage, left on the slag heap, literally. As Stuart himself says: “So many people suffered through a difficult time under Thatcher in the 1980s, and we were certainly all in it together.”

And yet we witness how among the poor and working class there is an unconquerable soul — battered, broken, brutalised — that refuses to give up hope. In fact, as Shuggie’s brother Leek complains, Shuggie’s problem is that he “was stupid enough to still believe”; that he refuses to surrender his mother to her addiction and accept Leek’s advice that “the only thing you can do save is yourself”.

Instead, after every thrashing, his instinct is to find a way to reignite hope and bring order to their lives.

But believe me, this is no syrupy idealised story of mother and son love. It is enduring love in a time of Carlsberg Special Brew, Valium and vomit. It is a love that, tragically, many cannot sustain and protect.

To achieve all this, the book’s power is its language and writing style. Its intimate observations of character and setting are Dickensian in their raw detail. Stuart’s strength is that he can observe behaviour and character in minute detail and then deploy language, a “poetic prose” that is sustained over hundreds of pages, to bring these characters and their time to bear on all of our senses.

In an interview at the 2020 Edinburgh Book Festival Stuart admits that being a visual designer gave him an advantage as a novelist. He is also aided by the fact that it’s an intensely personal story, his own childhood roughly corresponded with that of Agnes and Shuggie. But amazingly the author’s nowhere intrudes into the story.

Shuggie’s story begs no assistance. It can tell itself. It’s a political book, consciously rooted in a canon of Scottish working-class literature. But there is no guiding authorial hand to pontificate on the politics and injustices of the age. Stuart explains this style as being because he “didn’t want readers to gawk at people I love” but “to become immersed” in the context and its characters.

Thus, from page one we get set adrift in a sea of human flotsam where love and hate are often inches apart; where romance and rape are two sides of the same coin; where social security — the giro, the Monday Book and the Tuesday Book — are a lifeline t0 both food and alcohol.

The truth is that in this novel Glasgow is all the world’s stage. The 1980s and 1990s are the setting for a period piece with timeless and universal themes, but themes that are particularly acute in our age of division and despair. Although Glasgow might be a million miles from South Africa, the goings on at Pithead and Sighthill are the story of our own peoples’ broken lives, and at a time of unprecedented unemployment, alcoholism and substance use, a very timely one.

Interesting, for South African readers, is how one of the only tentacles that stretch beyond Glasgow’s borders is to our own South Africa. In the ears of Shuggie, “Joanna’s Bird” is the place where his sister Catherine, married as soon as she came of marrying age, flees with her working-class husband as an escape route from Agnes’s addiction. As he tells one girl: “My sister lives with black people a million miles away because of her.” Without any apparent irony or authorial overlay, the people of Pithead think of South Africa as a place where working-class and poorly educated mine workers disenfranchised in their own economy can once again acquire status and power over others.

And there’s the rub that makes capitalism so calamitous for poor people. I tried to read its penultimate chapter to a friend, but kept having to halt as emotions choked my voice.

Douglas Stuart’s art, imagination, fiction should be celebrated in its own right as great literature. However, as we leave Shuggie on stage, “all gallus” but facing a future as full of risk as the childhood he has just navigated in our presence, any reader beyond numbness will have to ask what do we do with the knowledge and feeling this story has helped us acquire and what is our obligation to our fellow human beings? DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thank you Mark what a beautiful and thought-provoking review. This book, Agnes and Shuggie have remained with me over the past few months.

What a fine and sensitive review. Your coverage of human issues in South Africa is always welcome and valued. Thank you. I look forward to reading the book.

Great review. However, I thought the book unrelentingly and unrealistically bleak. Other than Shuggie himself, his brother, and much later, Leanne, all characters (including the random ones – the taxi driver, for example, who abuses Shuggie) are devoid of goodness. Is this really a credible view of working class Glaswegians? And as for Agnes, she treats her children extremely poorly – even in her few sober moments. She is cruel, nasty, vindictive. I struggled to find the apparent special love that she has for Shuggie, despite his obvious love and dedication to her.