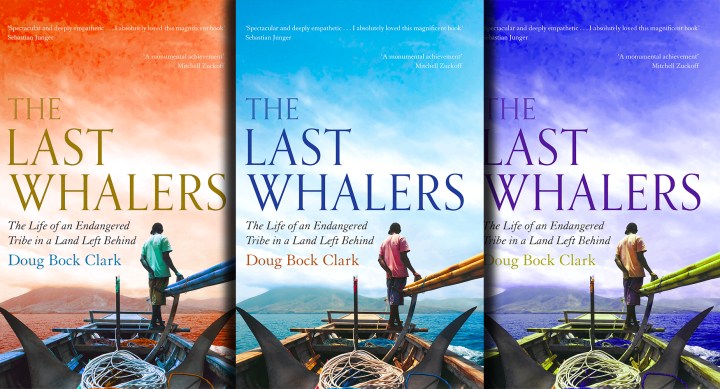

BOOK REVIEW

A lyrical look at hunter-gatherers and a fading way of life

In ‘The Last Whalers,’ Doug Bock Clark has produced a fascinating account of a tribe on a remote Indonesian island who still follow the ‘ways of the Ancestors’ in their annual pursuit of migrating whales.

This lyrical narrative takes us into the vanishing world of hunter-gatherers and as such offers a glimpse into our own distant past. As a 21st century recreational angler and hunter, this reviewer stands in awe of the Lamalerans. They are the Olympians of hunting, alpha predators who have perfected an ancient craft. From human-rowed and hand-carved wooden boats, they launch themselves, harpoon in hand, onto sperm whales, using their own bodies as part of the projectile, to impale the animals. They are the Maasais of the sea, but their quarry far outweighs a pride of lions.

Let’s put this in some context: the sperm whale is the largest toothed-carnivore on the planet — the giant squid forms part of its diet — and so to take one on in such a physical manner is nothing short of astonishing. It takes serious skill, agility, strength, timing and courage — with maybe a bit of lunacy for good measure. The results can be fatal, and not just for the leviathans. Bull sperm whales can weigh over 60 tonnes and the wooden boats the whalers use, called tena, can be battered by the beasts, while harpooners may find themselves entangled in ropes and pulled into the depths. Small wonder the hunters are exceptional swimmers who can hold their breath for long periods of time. Elite athletes who stand out from the rest of the global hunting pack.

But the book is about much more than the hunt, as riveting as that drama is in Clark’s masterful prose. It is about the vanishing ways of the hunter-gatherer — the way of all of our ancestors — and how one remote outpost of this culture is coming to often reluctant terms with the 21st century. A WWF campaign figures in this narrative, which ultimately got harpooned and lampooned.

“At the heart of the conflict,” Clark writes, “are contradictory ways of looking at how natural resources should be utilised. For the Lamalerans, the very idea of conservation is foreign: after all, if whales are gifts from the Ancestors, the only way to exhaust them is by using up the spirits’ goodwill, and to decline to hunt a proffered animal is to insult their forebears. Besides, the Lamalerans feel, their hunt has been sustainable for centuries — it is primarily pollution, overfishing, and climate change caused by the conservationists’ very own societies that are damaging their ecosystem. Why are the conservationists targeting them rather than more influential bad actors?” In fairness to conservationists, they also target the more influential bad actors, but the broader point here still has currency.

“History has shown time and again that depriving indigenous people of their livelihoods often leads directly to their end, as they lose their identities within a generation. After all, who are whalers who do not whale?” Clark notes.

“Even in positive scenarios … not all development is beneficial. Progress also means that something is left behind. At least half of change is always loss. The craze in advanced societies to reconnect with our past selves — from paleo diets to New Age spiritualism, to wilderness retreats, to the many ways in which we romanticise indigenous peoples — suggest that citizens of those nations intuit that they are missing something.”

Some critics might accuse Clark of romanticisation as well, but I think that would be unfair. In an objective and highly-readable manner, he has chronicled the challenges confronting a hunter-gatherer society in a far-flung part of Indonesia as the forces of modernity intrude into their lives. One compromise that has been reached in recent years is that motorised craft can be used in pursuit of the smaller species the Lamalerans also harvest, such as dolphins and rays. But the sperm whale can only be hunted by a human-propelled vessel to the ringing battle cry of “Row like you want to feed your families!”

And while Clark does not explore this theme explicitly, for this reviewer it adds credence to the ‘Overkill’ hypothesis which holds that the global wave of megafauna extinctions tens of thousands of years ago was triggered by paleo hunters. If a human can kill a sperm whale with a harpoon they sink into the flesh under their own weight, surely the same could be done to a mammoth which stands in diminutive contrast. My own view on that is pretty unromantic: I have raised the possibility previously in this publication that this was rooted in human/wildlife conflict.

But that speaks to terrestrial conflict and the habitat we share with wildlife. The Lamalerans are not in conflict with whales, which for obvious reasons pose them no immediate danger. They are a source of protein offered up by the Ancestors. And when the last whaler has flung himself from a wooden boat brandishing his harpoon, who will be left to honour the Ancestors? DM/ ML/ OBP

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.