OP-ED

Why are established trade unions comfortable with the status quo and threatened by the rise of Saftu?

Frustrating as this may sound, it is the duty of the progressive forces to find common ground with all workers, including rank-and-file whites in Fedusa and those in Cosatu whose leaders have been captured to defend the status quo.

The history of South Africa is a history of class, race and gender struggle.

The history written by the colonisers claims that diamonds were discovered in 1867 near the Orange River and gold in 1886 at the Transvaal farm Langlaagte.

This was a period following the near defeat of our people by the invading army of white colonialists who were now plundering the land from topsoil down to its bowels, in search of wealth.

But then they clashed among themselves immediately after these great discoveries, leading to two Anglo-Boer wars, in 1880-81 and 1899-1902. Eventually they settled by creating the Union of South Africa in 1910, which gained its full independence in May 1961.

The colonised black majority was excluded in most of these processes even though they were made to fight in the Anglo-Boer War, First World War and Second World War.

When they saw for the first time the degree of diamond and gold wealth, the settlers faced a problem: they did not have sufficient numbers of workers to help them bring these precious minerals up from underground. As was the case before, the settlers had brought the Indians to work as labourers in the sugarcane fields of Natal from 1860, and the Chinese for deep mines in Johannesburg, but the settlers also uprooted workers from Europe to help them plunder the natural resources of our motherland.

In his 1916 book Imperialism, Vladimir Lenin quoted from a statement made by Cecil John Rhodes (in 1895):

“I was in the East End of London (a working-class quarter) yesterday and attended a meeting of the unemployed. I listened to the wild speeches, which were just a cry for ‘bread! bread!’ and on my way home I pondered over the scene and I became more than ever convinced of the importance of imperialism… My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e., in order to save the 40,000,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands to settle the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines. The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists.”

Distorted labour traditions, as class war degenerated into racist solidarity

But there were contradictions: the French Revolution, the (unsuccessful) 1848 workers’ revolutions and the Russian Revolution of 1917 heavily influenced these settler-workers, who were considered surplus populations in Europe. They brought some of the most militant traditions to South Africa.

They wasted no time in creating their own trade unions in South Africa, many of which belonged to the International Socialist League, which was formed in South Africa in 1915. They helped form a Labour Party in January 1910. They developed mutual aid associations such as worker-controlled building societies and insurance companies. Some of these institutions inspired poor and working-class Afrikaners to do the same in the 1930s Economic Movement.

These militant trade unionists, however, eventually adapted to the completely different political and economic arrangements associated with settler colonialism. The indigenous black workers were not afforded the same rights and dignity in either the country’s capitalist enterprises or in many of the new unions.

They were brutalised, humiliated and forced against their will to work in the farms, factories and mines. Their land was taken from them and all their resistance broken through the introduction of all manner of tricks. These included the hut, poll and dog taxes, to force them to leave their land and work long distances away, as migrant labour systems began to predominate in the late 19th century. The very diamonds and gold that they had been brought to help dig represented stolen property.

Despite European workers coming from traditions of resistance to injustices, they never called a single strike to protest against the dehumanising treatment the indigenous people were subjected to. Instead of spearheading the formation of non-racial trade unions that could have built solidarity between black and white workers, these white workers embarked on a mineworkers’ strike in 1913 to demand recognition of the trade union and for the formation of a socialist South African Republic.

The African mineworkers had tried to join the strike, raising their own grievances, demanding a rise in pay to just two shillings a day. They were brutally stopped by the police who confined them to their hostels and they were soon forced back down the shafts facing the barrel of the gun.

The Rand Rebellion broke out in 1922 led by prominent leaders of the Labour Party. The rebellion had started as a white mineworkers’ strike in December 1921. The newly established Communist Party of South Africa had also played a leading role in mobilising for the strike. Prime Minister Jan Smuts was to successfully crush the strike with 20,000 troops and the first use of an air force against a civilian population in the western working-class neighbourhoods of Johannesburg.

Smuts soon faced a backlash after he handled the strike on behalf of mining capital and was defeated in the elections of 1924 by a coalition of the National and Labour Party. These parties introduced the Industrial Conciliation Act, Wage Act and the Mines and Works Amendment Act in 1926. These laws sought to recognise the white unions and introduced measures that meant that certain categories of work were reserved for white workers and that they should never be paid the same in law.

The far-right Herstigte Nasionale Party (Reconstituted National Party) won elections in 1948 – again defeating Smuts – after campaigning to address the white poverty problem. They introduced a barrage of apartheid laws.

While the Communist Party of South Africa was to later champion non-racialism and played a leading role in the establishment of non-racial unions after the Third International decreed alliances with nationalists in 1928, the racial divisions among workers had taken such deep root that we know of no strike led by white workers protesting against the brutalisation of black workers in South Africa.

Slowly the white workers were sucked into the status quo. Soon they had established a class of foreman and managerial workers which demanded that black workers call them “baas,” as they were being called on the farms and in all other sections of the economy. The white labour aristocracy mistreated fellow workers and became the face of apartheid in the workplace. They enjoyed separate amenities and brutally enforced this segregation. Recall the case of Jeffrey Njuza who was killed by a white worker for using a cup reserved for white workers.

White workers did not only enforce separate segregation in the workplace but also enforced it in the black residential areas – the townships and rural areas. They were conscripted as “kitskonstabels”, and manned roadblocks to enforce the curfew and to crush the resistance of black workers.

After hundreds of years of colonialism, capitalism and apartheid, the white worker had become a major beneficiary of the status quo. These benefits are countless, and included better wages, better opportunities for promotion or to even find a job, better schools, better everything.

Over a period, the once-socialist militants who had taken up arms to overthrow the government in 1921 turned out to be defenders of capitalism, racial discrimination and the system that was declared a crime against humanity by the United Nations. Even though the culture of forming and being part of the unions was rich, suddenly the unions were not as strong as they used to be. Why strike when everything is given to you on a silver platter based on the colour of your skin? The unions that remained become extremely conservative and organised mainly to defend the status quo.

The disbandment of the South African Trades and Labour Council (SATLC) completed the process in 1954, after failing to organise workers based on non-racial principles. A new federation called the Trade Union Council of South Africa (Tucsa) organised mainly white workers and excluded Africans, had broken away from SATLC. Tucsa was opposed to socialism as an ideology. The union was ultra-conservative and openly defended both capitalism and apartheid. Tucsa refused to join the strike called by the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu) in 1982, in protest against the killing of another (white) unionist, Dr Neil Aggett. As the fight against apartheid was intensifying, Tucsa was increasingly discredited.

Out of the remnants of Tucsa emerged the Federation of South African Labour Unions – (Fedsal) and the Federation of Organisations Representing Civil Employees (Force). These unions later amalgamated to form the Federation of Unions of South Africa (Fedusa) in 1997.

While Fedusa (or even Tucsa for that matter) attracted some black unions, its history has made it conservative. Fedsal and Force (the Fedusa predecessors) had in 1985 refused to form part of the unity talks leading to the establishment of Cosatu. Fedusa’s predecessors never called a single strike against apartheid, or against the incarceration of Nelson Mandela, or the mowing down of black people in the townships or for any other reason.

The closest to a mass mobilisation by Fedusa was only in the last decade, against e-tolls and corruption (in particular, opposing the 2017 dismissal of the then finance minister, Pravin Gordhan). Even in these occasions, the overwhelming number of Fedusa members would not join the protests, preferring that every dispute – even in their own interests – be referred to arbitration. The roots of this passivity is in Fedusa’s history, given that the culture of strikes and mass mobilisation among white workers died long ago, as they became part of defending the status quo against the interests of the majority.

The post-apartheid deformation of black trade union traditions

“A democratic republic is the best possible political shell for capitalism, and, therefore, once capital has gained possession of this very best shell, it establishes its power so securely, so firmly, that no change of persons, institutions or parties in the bourgeois-democratic republic can shake it.” (Lenin, The State and Revolution, 1917)

The history of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) is better known, so there is no need to provide all the details. Cosatu became a home of militant and democratic unions that re-emerged from the historic Durban strikes between 1971 and 1973. The apartheid regime was forced to appoint the Wiehahn Commission in 1979, which led to the recognition of black workers as workers instead of being seen as just forming part of the machinery.

It is also not necessary to explain why Cosatu’s first campaign was to demand the scrapping of apartheid pass laws and the Bantustan system. Nor is there a need to elaborate on the heroic role Cosatu played in the dismantling of the apartheid system and the improvement of wages and conditions of black workers.

It is also not necessary to talk to the history of the fourth largest federation in South Africa, the National Council of Trade Unions (Nactu). In brief, Nactu is a creation of a merger between the Council of Unions of South Africa (Cusa) and the Azanian Confederation of Trade Unions (Azactu). Cusa played a leading role in the unity talks that led to the formation of Cosatu yet refused to join following disputes about the founding principles of Cosatu, in particular non-racialism.

The purpose of what follows is not to dwell on the history of trade unions but to address how unions in South Africa were trapped into the defence of the status quo after 1994.

Let us reiterate that there is no dispute that Cosatu played a leading role in the battle against the apartheid system. Cosatu formed part of the Tripartite Alliance led by the African National Congress. All of the components of the Tripartite Alliance undoubtedly formed part of the biggest formations that led the struggle for the attainment of freedom and democracy in South Africa.

It was from this political dominance – not just because of its size but also because of the legitimacy and indeed prestige Cosatu has enjoyed, precisely because of the militant role it has played – that Cosatu became such a factor in all the processes of transformation prior to and after 1994. To illustrate, in the dying days of apartheid, Cosatu – in some instances also with the support of Nactu – engaged in the campaign against the Labour Relations Act amendments, the unilateral neoliberal restructuring of the economy, and the introduction of Value Added Tax (VAT), against which Cosatu organised a strike of 3.5 million workers in 1991.

It is from this advantage that Cosatu played a key role in the “transformation of South Africa” across the board. This meant “everything must change”, as the musical icon Hugh Masekela put it in a song. Obviously, where the government had an influence after 1994, transformation was relatively deeper, but where the private sector controlled things, transformation happened at a snail’s place. The Employment Equity Commission reports about deracialising workplaces and management hierarchies demonstrate this point.

Since government departments went through deep changes, Cosatu was in the thick of things. However, even this transformation of the state tended to be more about the change of faces and races to match the society’s demographics, rather than a deep transformation of the state’s systems or governing values.

Education crisis, especially for low-income black South Africans

For example, in the education sector, the heads of department, the principals, the district inspectors, the directors at all levels and the minister were changed, and Cosatu unions drove this change to the huge personal benefit of cadres who were often at the leadership levels. But the education system remains poor, and its quality remains extremely poor, because the earlier hunger to change the system had ebbed.

South Africa has one of the most corrupt and poorly managed education systems in Africa. Of every 100 children who enter the education system at Grade 0, only 50 complete matric and of these only 14 qualify for tertiary education. To keep the pass rate respectable, an extraordinary “culling” of children in grades 9-11 occurs annually, with a tragic dropout rate leaving our youth unemployed and alienated.

Though the matric pass rate stood at 72% in 2016, this reflects only the performance of learners who managed to stay in school for 12 years and obscures how many dropped out along the way. Of the Grade 2 class enrolment, only 668,612 students made it to the 2016 matric final exams, a massive drop-out rate of 44.8%.

One reason is that free education at all levels is still a dream for most young South Africans. Coping with the cost of education for poor families remains a nightmare.

South Africa has far greater resources, yet the quality of public education is far worse than that of counterparts in the region, such as Eswatini, Botswana and Zimbabwe. In 2015, the World Economic Forum rated South African science and mathematics education as the worst of 140 countries, and 138th in overall quality.

The unacceptably poor performance continued, according to a 2019 report of the Human Sciences Research Council in 2019 (released in December 2020): in Grade 5, “63% of pupils had not acquired basic mathematical knowledge and 72% had not acquired basic science knowledge. South African achievement continues to be unequal and socially graded, linked to socioeconomic backgrounds, spatial location, attending fee-paying versus no-fee schools, and the province of residence… Learners from homes that lack basic services like running tap water and flush toilets obtain lower achievement scores.”

The education system in our country largely reproduces the apartheid and colonial-era fault lines and traps the black majority in a vicious cycle of poverty, unemployment and inequalities. There is no need to belabour this matter any further.

Policing crisis, especially for women

Let us consider another example: security or policing. Cosatu union Popcru immensely benefited from “transformation” and its cadres were deployed to lead police stations, all the way to lieutenant-general. We are not arguing that other members of other police unions did not benefit. We are talking about the scales here.

But there are also depressing statistics regarding the state of the policing service to fight crime. The SAPS 2016 crime statistics recorded 51,895 sexual offences, but this is likely to be a big underestimate, as unreported rapes are estimated to be as high as seven times those reported.

Our judicial system is as sick as the perpetrators of crime. We are told that the police make arrests in less than half of all the crimes reported annually. Of those arrested, a meagre 42% eventually appear in court; the rest are released. And only 30% of the suspects who do appear in court are found guilty.

In 2009, according to the police statistics, the conviction rate for murder in this country was 13% and for rape, 11.5%. But other estimates in 2014 suggest the conviction rate is as low as 10%.

The privatisation of policing is a contributing factor, as armed security guards operate across the main cities’ wealthier suburbs, joined now by Vumacam operations that establish an entire non-state surveillance network of often more effective intelligence, undermining the state’s ability to tackle crime.

The justice system is dysfunctional and therefore women who are the most vulnerable members of society remain victims of the culture of impunity.

The police and courts are also often reluctant to treat violence against women, especially against partners, as seriously as other violent crimes. Rape victims often battle to prove that they did not consent to the act.

As Kathleen Dey of the Rape Crisis Cape Town Trust wrote in Independent Media: “In a country where rape culture underpins our gender relations and where violence of this kind is almost a norm, because we see it on a daily basis, perhaps we are not as shocked as we should be. And because we are not as shocked as we should be, perhaps we are not reacting as we should.”

This is what “transformation” has meant for society when it comes to the judicial system.

Unions must fight – and not be assimilated into – the status quo

We can make similar examples about almost everything in South Africa, including the state of public healthcare, correctional services, home affairs, social development, water and sanitation, electricity, housing, etc.

The principal point we are making is that precisely because Cosatu and its unions benefited from the status quo they have a reason to keep the status quo intact for selfish and narrow reasons largely reflecting the self-interest of leaders. These reasons include the former comrades’ ability to now afford to move their children to better schools in the former whites-only schools. They can afford to reside in the formerly whites-only residential areas, perhaps with security contracts. Few, if any, are to be seen in public transit, so their ability to relate to the massive transport crisis is limited. Some labour leaders can even afford the monthly instalments on German luxury sedans and can generally enjoy the living standards of the upper middle strata.

The status quo is sweet for the middle strata, but it has kept the majority of blacks deep within race, but also in both class and gender, terms at the bottom of the food chain. The status quo, in the form of the triple crisis of poverty, unemployment and inequalities, just keeps on getting worse.

For example, the official rate of unemployment now exceeds 30%, while the more realistic expanded figure (including workers who are not technically in the labour force due to discouragement or location) is above 40%, the highest level in the industrialised world.

Every worker has been affected by the jobs bloodbath, including the public sector, where the government, led by Cosatu’s alliance partner the ANC, has vowed to systematically cut wages by not adjusting them for inflation. The ANC’s commitment to austerity measures and neoliberalism worsens every day. Yet, Cosatu keeps on asking workers to vote for the ANC, as part of the defence of the status quo.

We need not provide other examples about the fast-worsening poverty and the extreme inequalities that have condemned our country to be the most unequal society in the world. We won’t talk about the runway corruption scandals that we read about almost daily, both in public and private sectors. We won’t talk about the corruption scandals in the unions themselves, including those that saw their way to courts, leading to the split of some of the Cosatu unions.

The point we are making is that both Fedusa and Cosatu wittingly and unwittingly find themselves defenders of the status quo that is anti-working class and black majority.

White workers have not found common ground with the former oppressed majority that led the battle against apartheid and who are militant and who are inspired by socialism. These unions never joined the four-year marathon discussion that produced Cosatu. They did not embrace even a breakaway faction to that faction, in the form of Nactu. Instead, they chose to form an alternative they could control politically, Fedusa.

Much later, Fedusa formed an unworkable confederation with Nactu. Yet, Fedusa refused to join with Nactu and a host of other independent unions to establish a new independent, democratic, militant, campaigning federation, notwithstanding the agreement to do so. It initially participated in early meetings and later just backed off, without engagement or explanation. It was to later threaten to take the new federation to court, based on the spurious claim that the Fedusa and Saftu’s names are similar.

Then Fedusa worked with Cosatu to block the participation of Saftu in the National Economic Development and Labour Commission (Nedlac), making another bizarre claim that only federations that have existed for over two years can participate. While doing so they signed an agreement for the introduction of a minimum wage of R20 an hour in 2017 and, in effect, supported Labour Amendment Act changes in 2019 that make it more difficult to strike. And, in contrast, they kept silent about a recently-published Deloitte report that exposed how the CEOs of the 100 top JSE listed companies were earning on average R17.9-million per annum.

Ongoing white male power in the status-quo workplace

The reason why Fedusa is not keen on unity is not difficult to establish. The benefits of the history we have spoken to in this article have not been dismantled. Apartheid and colonialism combined with a vicious capitalist order that is also a major beneficiary of past racism, have not been dismantled.

In business, after all, management remains largely white and male. The latest report of the Employment Equity Commission reveals that “the representation of the White group at the Top Management Level at 68.5% is more than six times” their share of South Africa’s Economically Active Population (EAP).

“The Indian group at 8.9% is also over-represented by three times their share of the EAP. On the contrary, the African group at 14.4% and Coloured group at 5.5% are under-represented in relation to their EAP. African representation is more than five times below their EAP, while the Coloured representation is half their EAP.”

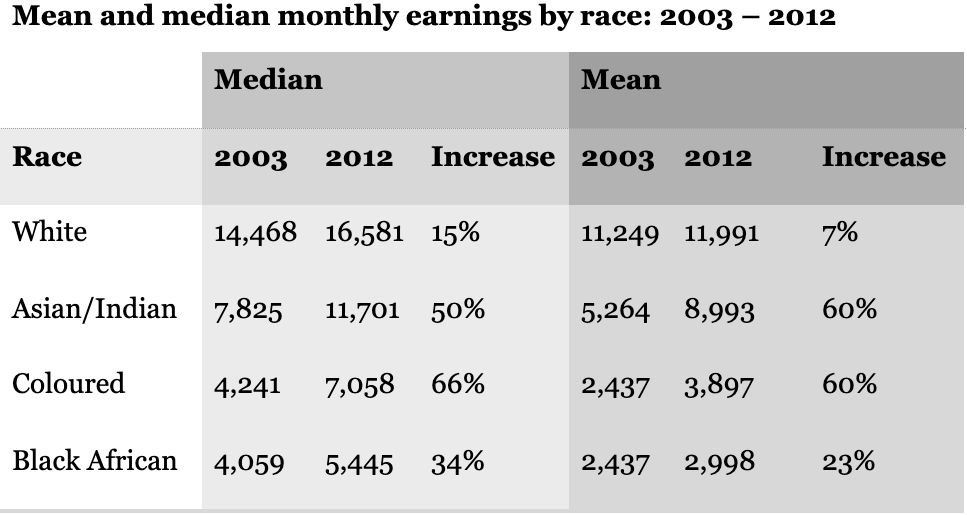

Second, wages still reflect the past racial-capitalist hierarchies. The StatsSA Living Conditions of Households in South Africa survey, detailing the average annual income of South Africans for a period of 12 months in 2014/15, shows that white South Africans still command the highest average incomes in the country at approximately R444,446 a year. This is more than 1.5 times greater than Indians/Asians at R271,621 per year, and almost five times more than black South Africans, at R92,893 per year. Black South Africans account for just over 80% of the country’s current population while white South Africans make up a little over 8%.

These wage differentials remain racially skewed even amongst the professionals. According to Analytico, a data and earnings analytic consultancy, the earnings analysis of genders (across different races) indicates major discrepancies: white male professionals out-earn their female counterparts by as much as 42% on the median earnings, while black female professionals out-earn their male counterparts by 17%.

White males working in the formal sector could expect to earn a median salary of R21,700 per month, while white males working in the formal sector as professionals could expect to earn a median salary of R30,453 per month. By contrast, black males working in the formal sector could expect to earn a median salary of R3,612 per month, while professionals could expect to earn R9,244 per month.

White females working in the formal sector could expect to earn a median salary of R13,331 per month, with professional females expecting to earn R17,700. For black females, those figures dropped to R2,887, and R11,155 respectively. Black females in the labour market have a greater probability of unemployment – at a rate of 13%, dropping to 6% for professionals.

Third, unemployment statistics also reflect these inequalities. Whereas unemployment among black Africans is well above 40%, unemployment among whites was hovering around 6% (pre-Covid-19), which is the same rate as many developed European countries.

This is the status quo in South Africa. We can offer countless examples, and each will reflect deep racial inequalities as configured by colonialism, apartheid and South Africa’s vicious form of capitalism. In this context, it is not a surprise that the leadership of Fedusa seems to be very reluctant to unite and find common cause with the black African majority. We blame this historical trajectory for the conservative framework of its founding congress of 1997, dating back to the character of the 1922 Rand strike and before.

Changing socioeconomic character of Cosatu and Fedusa

The unbanning of the ANC was followed by a massive increase in the rate of unionisation in the public sector. There was an outburst of militancy that has been bottled for many years.

The Bantustan leaders’ response to this increasing militancy in the public sector was mass dismissals and victimisation of the leadership. The 1994 breakthrough inspired more resistance and when those dismissed by the Bantustan leaders were reinstated, this saw even greater numbers of public sector workers joining young unions that were formed in the late 1980s.

This growth, however, coincided with the massive restructuring of the working class in the private sector. The private sector employers, now accustomed and more tolerant of the union militancy that they had to contend with since the 1973 Durban uprisings, had found a plan here in our country and elsewhere in the world.

They embarked on restructuring that saw them declaring hundreds of thousands of workers as non-core, outsourcing and using labour-brokering and contract work as a clear strategy to thwart and undermine the power of the proletariat class.

The first decade of democracy also saw massive deindustrialisation and job losses. To illustrate, the contribution of the manufacturing sector to the GDP was over 20% in 1994. It then declined to 12%. Some of this decline was due to the overall crisis of capitalism that persisted, but a great deal was the overly-rapid trade liberalisation foisted on South Africa by Trevor Manuel when he pushed for World Trade Organisation membership and concessions even greater than were deemed necessary. Other job losses occurred in areas like farming and construction as liberalisation, mechanisation and outsourcing shook up the labour markets, and as commercial farmers evicted tenant labour for fear they would demand land reform.

All these factors combined to change the composition of the Cosatu membership. A significant number had become police officers, educators, nurses and even doctors. In material terms, in terms of pay, these form part of the middle strata. It is the unity and solidarity with the industrial proletariat that has kept them more militant than they would be elsewhere.

But then there were two developments that are worth emphasising. The first one we have already addressed: the membership of the Cosatu unions was not associated with victimisation by the apartheid and Bantustans system. Leadership positions were now associated with upward movement and immense power to decide who in the state became the heads of department, or the school principals and district inspectors in the case of education as an example.

Secondly, this changed the material conditions of the leadership who are now principals and HR managers. Moreover, the “ladder” that takes Cosatu’s top leadership from union presidencies and secretary-general status into mayorships, provincial parliaments and the national Parliament – and in a few cases into the Cabinet – was also a degenerative factor. This helps explain the implosion of Cosatu in 2010-14. As one example of the potentials that were lost, a resolution was taken at the September 2012 Cosatu national congress to embark on a political strike so as to change a half-dozen core aspects of economic policy, in search of a “Lula Moment” which, like Brazil’s in the early 2000s under former metalworker Lula da Silva’s Workers Party leadership, decisively reduced poverty, unemployment and inequality. The strike would be based on criticisms that sound like a broken record:

- The role of Treasury, monetary policy and the Reserve Bank;

- State intervention in strategic sectors including through nationalisation;

- Measures to ensure beneficiation, such as taxes of mineral exports;

- Channelling of retirement funds into productive investment;

- Comprehensive land reform, and measure to ensure food security; and

- The more effective deployment of all state levers to advance industrialisation and the creation of decent work on a large scale.

The fact that we have moved backwards on many of these resolutions as the working class or made negligible progress on others (such as vitally-needed National Health Insurance), means that there were, in effect, eight lost years since the 2012 Cosatu resolutions. All these remain on the agenda for economic transformation today, even Cosatu leaders will admit.

During 2013-14, there were nearly a dozen Cosatu unions that opposed the dismissal of Numsa and others from the federation. In 2016, deciding to launch a new federation, they analysed the political development as follows:

- The real basis of the crisis in Cosatu is rooted in the complex and contradictory class relationships that Cosatu has to deal with, on a daily basis, in the multi-class and unrestructured ANC-led Alliance, to which it belongs.

- The failure of the liberation movement as a whole to resolve national oppression, class exploitation and the triple oppression facing women post-1994, and the rise of influence of black and African capitalist interests in the liberation movement, and the policies they pursue to promote their interests. As a result of this, the colonial and capitalist mode of production and its social relations have not been challenged or transformed, but have actually been strengthened in South Africa, thus worsening unemployment, mass poverty and extreme inequality.

- The failure to address the triple crisis of unemployment, poverty and inequality on behalf of the popular masses post 1994, threatens to overwhelm and destroy the liberation movement as a whole, and Cosatu in particular.

- The crisis in Cosatu is a reflection of the class contradictions and class struggles that are broadly playing themselves out between the proletariat and the forces of colonial capitalism and imperialism in South Africa as a whole and in the liberation movement and its formations.

- The crisis in Cosatu must be understood as reflecting the contradictions between those leaders in Cosatu who have been won over to the side of being apologists and defenders of a neo-liberal South African capitalism under the guise of “taking responsibility for the National Democratic Revolution” and those who are determined to continue to pursue a more radical NDR and the struggle for socialism as the only holistic and viable solution to the national, gender and class questions in South Africa and the world.

- What is at play in post-1994 South Africa is now becoming a battle between the forces of capitalist reconstruction, and the forces for socialism, as the only solution to the crisis of humanity and development in South Africa and the world.

After the dismissal of Numsa’s 340,000 members in 2014, the resignation from Cosatu of the second-largest proletariat organisation, Fawu in 2016, led to a situation where finally the majority of Cosatu members became public servants. The first, second, third, and fourth biggest affiliates of Cosatu are public sector unions. The biggest unions of Fedusa are public servants.

The public servants’ material conditions in terms of pay have improved over the past two decades. Contrast the salaries and working conditions of most state cleaners and security, with their (mostly casualised) counterparts in the private sector. The worsening conditions of workers in the private sector in farms, domestic work, community healthcare, early childhood practitioners, etc, make these workers more naturally angry about the status quo than the nurse and teacher would be.

Accordingly, based on increasing conservatism, the leaders of workers drawn from the ranks of the middle strata would be more tolerant of an Alliance that does not deliver the banning of labour brokers, for example, in contrast to the industrial proletariat which knows this casualisation is fatal to its interests.

Cosatu and Fedusa are not alone in facing challenges of rampant capitalist expansion

The working classes of the world, as Marx wrote in 1852, “make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

We live in a capitalist system which inculcates values that are directly opposite to the interests of those held by the working class.

The values of the other side are centred on individualistic selfishness, “Me first!” and to hell with everyone else, crass materialism and environmental destruction, sexism and patriarchy so that women’s unpaid work continues, racism and xenophobia, homophobia, ableism, etc.

Under a dominant system of capitalism these values have moved from corporate boardrooms into the trade unions, non-government organisations, mass formations of the working class, religious formations, youth and student organisations, etc.

Whenever these values permeate into our formations, turmoil follows, and even the strongest leaders find themselves sabotaged.

It is not only the Cosatu unions or more established unions that are facing the danger of corporate capture. The spectre of business trade unionism may be one of the reasons why workers in the private sector have also begun to lose trust in unions. If union leaders appear to be preoccupied with building up personal assets and forgetting about workers’ day to day concerns, then workers will withdraw their support.

As soon as the union is awash with resources from investment companies, for example, allegations fly over whether the leadership is using these resources to amass wealth for itself, getting benefits that tend to weaken internal democracy. The interests of the service providers in who becomes the leader of the union have become legendary. The reason why this is the case is also well documented within trade unions with investment companies. The instability this has caused is also well recorded in the past 26 years of democracy.

We also know that former militant unions that were growing and stable are now under administration and have literally been taken over by the bureaucrats of the Department of Labour. We know that unions that enjoyed stability from the inception are now engulfed in destructive factional wars that have defocused the leadership from top to bottom, leading to the weakening of the commitment to serve workers.

This is a capture of our internal trade union principles, not terribly different from how, externally, unions have been muted by capital and the state.

How should we navigate this complex situation?

Frustrating as this may sound, it is the duty of the progressive forces to find common ground with all workers, including rank-and-file whites in Fedusa and those in Cosatu whose leaders have been captured to defend the status quo. This is a big and necessary debate Saftu should have: where are our best prospects for alliances with workers who may have longer-term socialist interests but whose immediate perceived interest is backing status quo unions during the worst crisis capitalism has experienced in our lifetimes?

This is the time when our unions must rise to the occasion: defending worker rights, fighting Treasury austerity, demanding jobs for all and a Just Transition, building basic-needs infrastructure, reindustrialising and localising properly, insisting on tighter Reserve Bank exchange controls, implementing National Health Insurance urgently so as to fight Covid-19 for months or years to come, dealing with ecocide and climate catastrophe so our next generations can live a good life, ensuring an end to both the root causes and ghastly symptoms of gender-based violence and xenophobia, eradicating racism once and for all, opposing imperialism and South Africa’s role as deputy sheriff in the multilateral institutions and G20, and making common cause with all the solidaristic workers and oppressed peoples in every corner of the world.

This is not the time, nor is there ever any such time, for trade unions to defend the anti-working class status quo. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I have difficulty believing anything this man says. He was a key cog in foisting the obnoxious Zuma and his thieving bloodsucking cronies onto this wasteland of a country it is today – remember the comments about the unstoppable tsunami. He then carries on about the left and the progressive forces, conveniently forgetting that idolised countries such as China, Russia, Cuba etc. don’t even allow dissention in any form, let alone trade unions. I don’t doubt his sincerity, but to my mind it is wayward. The world has changed and whilst trade unions are important, in SA we have trade unions that are militant and stuck in the past with failed policies etc. They are a huge ball/chain around SA’s neck and need a life-changing reality check.