OP-ED

Wayward Boy: Stumbling into exile on a wing — and a prayer from Dominee Du Toit

Despite my nervousness, going into exile over the Easter of April 1965 turned out to be remarkably easy. Less than a week after disappearing from Johannesburg, I was in Salisbury (Harare) in what was then Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). But I was broke and needed a job. Then, within weeks, aided by blind luck and some brazen cheek, I was illegally in Zambia and appointed chief reporter of the daily Times of Zambia at twice what I had ever earned before. Less than four months later, everything came unstuck.

Shortly before Easter of 1965, I effectively vanished. Inasmuch as I had a plan for leaving the country, this was it: hint at heading for Swaziland and then, after a few days, join the annual Easter “rush” across the northern Beit Bridge border post into what was then Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) using my dubiously acquired Protectorates Travel Document.

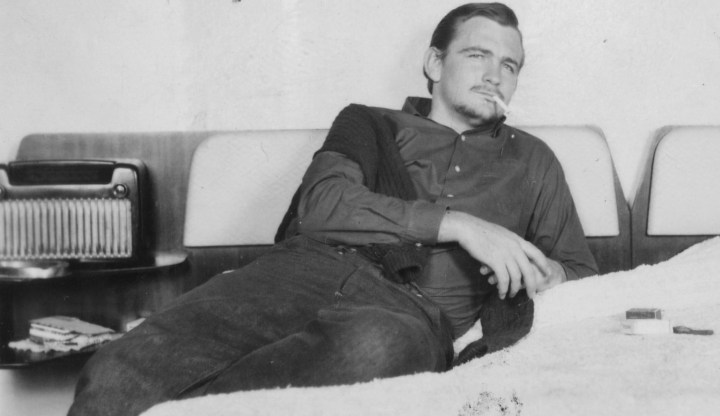

So, the night after I hitchhiked out of Johannesburg, I walked the last few miles into Amersfoort and slipped into what was then the Indian ghetto of shops and homes in the centre of town. Baboo Bilai, one of those who had earlier illegally crossed into Swaziland with me and members of the Fordsburg group, was happy to put me up. His and the other families understood the need for a white friend to remain out of sight while staying in the ghetto. For “memory’s sake” Baboo snapped a picture of me sprawled on his bed in my “James Dean pose” which he posted to me more than 50 years later.

Before dawn at the start of the Easter weekend, I said farewell to Baboo and jogged out on to the road to Pretoria. Just north of the capital, a car stopped. I doffed my hat as I shook the outstretched hand of the driver. He introduced himself: “Du Toit, Dominee Du Toit.” A dominee, a Dutch Reformed Church minister. Surely no official would think of questioning someone travelling with an Afrikaner man of the cloth? In the formal pleasantries that followed, it turned out that we were probably distantly related: my mother’s family were Du Toit and Joubert, and we shared the ancestry of Huguenots who had arrived in the Cape in 1688.

That sealed it for the dominee. He was driving up to a church mission in Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) while I was heading for Salisbury (Harare). He originally offered to drop me off in Fort Victoria; now he insisted I should stay over at the mission. After breakfast, he would drive me to Salisbury. I thanked him profusely and, after he had intoned a prayer for a safe journey, we were on our way.

The Beit Bridge border post was, as I had hoped, a clutter of cars and a jostle of people. But I suddenly felt very conspicuous, although nobody paid me the slightest attention. I placed my hat on the long counter and filled in my immigration form before nervously handing it and my “passport” to an immigration officer. He took the form, stamped the document and, without even looking up, waved me on.

I had to suppress a feeling of panic until I spotted the Rev Du Toit, waiting by his car. I could have hugged him. Instead, I got into the passenger seat and, after his customary prayer, we trundled off across the bridge that to me signalled freedom.

The churning in my gut had started to subside as we reached the Rhodesian bank when Dominee Du Toit noticed that I didn’t have my hat. It didn’t matter, I explained. I could always buy another hat and, besides, I didn’t want to delay the good reverend.

But he insisted: “Oh, my boy, but you must go back and fetch it.”

What could I do? And so I embarked on what I remember as the longest walk of my life, back into South Africa to fetch my hat. I felt physically ill as I re-entered the border post. The hat was on the counter where I had left it and nobody paid any attention as I slammed it onto my head, turned and bolted back across the bridge to where the dominee was waiting.

I don’t remember anything of the drive to Masvingo, the stay at the mission, who I must have met and even what I ate. But, the following morning, Rev Du Toit was as good as his word; I was dropped off in Salisbury at the local YMCA.

With only R13 to my name, I needed a job to tide me over until I could move north and make contact with the exiled ANC. There was nothing going at the local Herald newspaper, then part of the Argus Group that owned newspapers from the Copperbelt of newly independent Zambia to the major dailies in Cape Town. But, said the Herald editor, the Northern News in Zambia was “desperate for subs (sub-editors)”. I could use his telephone to call the editor of the News.

The only question I was asked was, “how much do you want?” I quoted £25 a week (about twice my previous pay level) and the editor agreed immediately. But it seemed I had to deposit a refundable £150 at the border on entry.

“Don’t have that sort of money with me at the moment,” I said.

“No problem, we’ll cable it to Chirundu (border post) today,” he said.

I was ecstatic. With that amount of money already cabled, no official was likely to look too closely at a “passport” that did not allow me entry into Zambia. That assessment proved true and I was stamped into Zambia with a “welcome” from the immigration officer.

After three months, when I applied for Zambian residency, it was discovered that I had entered the country on an invalid document. The South African police also requested my extradition and there were references to the fact that another South African exile, Dennis Higgs, had earlier been kidnapped from Lusaka. He was later found, bound and gagged, in a park in Johannesburg.

I headed straight for Lusaka and the ANC office – and my first major letdown. Somewhat downcast, I headed to the newspaper offices in the Copperbelt town of Ndola to discover that the colonial-era Northern News was about to become the Times of Zambia. There would also be a new editor: journalist and independence campaigner Richard “Dick” Hall.

I couldn’t have been happier. Then a second freak of chance landed in my lap: the chief reporter, newly recruited from Britain, was a native of Newcastle upon Tyne with a pronounced “Geordie” accent. It was decided that most people in Zambia might have difficulty understanding him. And so it was that I became chief reporter and Terry Ryle moved to the sub-editors’ desk. Instead of being office-bound, I was out and about, reporting on a country having newly won political independence, for a newspaper that was shedding its colonial inheritance.

I met and interviewed President Kenneth Kaunda and members of his cabinet, covered the start of the Chinese-built Tazara Railway to Dar es Salaam and learnt about Zambia’s ethnic complexity while becoming the unofficial speechwriter for the newly appointed provincial governor of Ndola, Levi Mbulo. It was an immensely exciting and productive, but all-too-brief period.

After three months, when I applied for Zambian residency, it was discovered that I had entered the country on an invalid document. The South African police also requested my extradition and there were references to the fact that another South African exile, Dennis Higgs, had earlier been kidnapped from Lusaka. He was later found, bound and gagged, in a park in Johannesburg.

On this basis, President Kaunda announced that, for my “own personal safety”, he was seeking asylum for me in another country. It all sounded very dramatic but was, in fact, a matter of some deft politico-legal footwork: at the time, Zambia was dealing with a massive influx of refugees from Mozambique and Angola. If the Zambian government allowed me to stay, it would set a precedent and thousands of Angolans and Mozambicans fleeing warfare in their countries could also claim residence in Zambia.

That was how, in August 1965, armed with a letter from the British High Commissioner in Zambia, I was given the right to enter Britain. I still had my hat, my rucksack and my boots, along with a slightly larger wardrobe, and, from Dick Hall, an introduction to Derek Ingram, then assistant editor of the Daily Mail in London. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.