This story was first published in New Frame

Last month, at the age of 71, Bruce Springsteen released his 20th studio album, Letter to You. The opening track, One Minute You’re Here, is a reckoning with mortality, with the “Big black train comin’ down the track,” a reckoning that means an affirmation of the life that remains.

Springsteen survived the extraordinary fame into which he was thrust in 1984 with the massive global success of Born in the USA. He didn’t go the way of Jimi Hendrix or Kurt Cobain. His band didn’t explode like The Clash in a brief but brilliant supernova. He didn’t end up like the Rolling Stones, with a steady supply of blues riffs but lyrics and a posture that slowly became a caricature of the vital young band that burst out of England in the 1960s. Mick Jagger might be 77, but he didn’t seem to ever move beyond being that young man, hungry for life, in tight trousers.

Springsteen’s artistic integrity survived too. Many of the characters in his best-known songs from the 1970s and 1980s were young men, often in cars, trying to get out of dead-end jobs in dead-end towns. That movement towards the future took the form of operatic bombast and the promise of some kind of redemption in the rushing, crashing wall of sound of Born to Run. But there were also more elegiac songs, like Racing in the Street or Stolen Car, in which the movement towards the future was either movement into a brief moment of exhilaration in an otherwise bleak landscape, or into uncertainty, risk and darkness.

As he aged, the characters in Springsteen’s songs moved from being young men in cars to men in the home: fathers and husbands. And now, on his recent album, they have become men approaching the end. Men who – as they outlive many of the people they have loved – only see those who have left in their dream life, and who prepare to take their own place in the dream life of the people they will leave behind.

Given the Catholic inflection that has marked all Springsteen’s work, despite his alienation from the church, it might not be too much of a stretch to suggest that, perhaps, his 20 albums can be counted out, like beads in a rosary marking the arc of life, of the moments that give it weight, consequence and meaning.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/21Nov_Springsteen_AE5.jpg)

Finding Elvis and Steinbeck

In his 2016 autobiography, Born to Run, Springsteen returns to a decisive moment in his understanding of the possibilities of popular music. In 1956, at the age of six, he saw Elvis Presley’s first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. It was, he wrote, “a moment of light, blinding as a universe birthing a billion new suns, there was hope, sex, rhythm, excitement, possibility, a new way of seeing, of feeling, of thinking, of looking at your body, of combing your hair, of wearing your clothes, of moving and of living.”

But he has also often spoken about how, later on as a young man, he saw John Ford’s 1940 cinematic adaptation of John Steinbeck’s great 1939 novel, The Grapes of Wrath, on television. “The humanism in that,” he later recalled, “was something that touched me deeply, deeply. And I thought I want some of that in my music.” He would go on to read Steinbeck’s novel and listen to The Ballad of Tom Joad by communist folk singer Woody Guthrie, who composed the song in 1940 immediately after seeing Ford’s film in New York.

Steinbeck’s novel is about people who have been indebted, forced off their land – made poor – and are now migrants moving in their rattling cars on Route 66 from Oklahoma through Texas, across the mountains of New Mexico, down into the Arizona desert and on to California in search of work. The Joad family, and others travelling with them, suffer loss, endure indignity and encounter contempt at every turn. It’s a hard, hard road increasingly held together by women. The distance that must be traversed is marked by misfortune, hunger and corruption and violence from guards, cops and vigilantes.

Steinbeck’s novel and the same is true of Ford’s film, is not just an empathetic account of impoverishment. When the Joads finally reach California and find some work in the orchids, they are mercilessly exploited. The police support the bosses and there is violent conflict.

‘An army without no harness’

As the novel builds to its climax, Jim Casy, a preacher, concludes that there’s “an army of us without no harness” and commits to support the organisation of the workers. They make progress in organising their settlement, getting to the point at which “[f]olks is their own cops”. But then a strike is broken. “[T]hey drove us like pigs. Scattered us. Beat the hell out of fellas,” he tells Tom, the Joads’ son.

The developing unity among the migrant workers from Oklahoma is seen as a threat by the landowners in California. Two cops identify Casy as a leader. One calls him “a red son-of-a-bitch,” the other crushes his skull with a pick handle. Tom grabs the pick handle and with four blows beats the life out of the cop who has just murdered his friend. He finds refuge in a cave hidden by a mound of blackberry bushes.

In the cave, during the last conversation with his mother, Ma Joad, before he flees, Tom wonders why they can’t “[t]hrow out the cops…work together for our thing – all farm our own land”. Ma Joad asks, “What you gonna do?” Without hesitation, he answers, “What Casy done.” She replies, “But they killed him.”

“Ma,” Tom explains, “I have been thinkin’ a hell of a lot, thinkin’ about our people livin’ like pigs, an’ the good rich lan’ layin’ fallow, or maybe one fella with a million acres, while a hundred thousan’ good farmers is starvin’. An’ I been wonderin’ if all our folks got together.”

Again, Ma Joad tells her son that this is the road to death. He replies, “Well, maybe it’s like Casy says. A fellow ain’t got a soul of his own, but on’y a piece of a big one – an’ then … Then it don’t matter. I’ll be ever’where – wherever you look. Whereatever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there.”

An implicit politics

But Springsteen’s work didn’t begin with this kind of militancy. There was, of course, an implicit politics from the start in the songs about working-class men trying to move out of the life to which they had been consigned. By 1978, that had become clearer in Darkness on the Edge of Town. In Factory, a lament for lives crushed under the weight of work, he sang:

End of the day, factory whistle cries,

Men walk through these gates with death in their eyes.

And you just better believe, boy,

somebody’s gonna get hurt tonight.

The implicit critique of society continued on Nebraska, the stark acoustic album released in 1982. The characters on this album are often working-class people who have fallen on hard times and see no way out. In 2020, Springsteen said that he had drawn considerable inspiration for the album from radical historian Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, which was published in 1980. But while the album certainly invokes Zinn’s respect for the people usually as invisible to art as they are to history, it has none of Zinn’s focus on organisation and struggle.

In June 1984, Born in the USA exploded into massive success with seven top 10 singles. It remains one of the biggest-selling albums of all time. With songs about the Vietnam war, unemployment, a 1960s race riot, personal loss, and brief moments of joy ending in encounters with cops and judges, there’s a clear set of critiques of American society.

But for many listeners, including, famously, Ronald Reagan, the actual content of the lyrics was masked by the infectious melodies and riffs. For some years, Springsteen would only play a stripped-down blues version of the title track, with the aim of avoiding any misunderstanding of a song about a Vietnam veteran who comes home to find himself without work:

Down in the shadow of the penitentiary

Out by the gas fires of the refinery

I’m ten years burning down the road

Nowhere to run, ain’t got nowhere to go

Searing Expositions

The five-record box set Live/1975-85, released in 1986, includes the first live release of the song Seeds, which had never been released on a studio album. This version, recorded in 1985 at the summit of Springsteen’s fame, is a raw, powerful angry song – perhaps his first militantly political song without the disguise of a beguiling chorus. Without making explicit reference to The Grapes of Wrath, it brings Steinbeck’s description of newly impoverished people, sleeping in their cars and hounded by the police to move on, into Reagan’s America.

Parked in the lumberyard freezin’ our asses off

My kids in the back seat got a graveyard cough

Well I’m sleepin’ up in front with my wife

Billy club tappin’ on the windshield in the middle of the night

Says “Move along man move along”

In 1993, Springsteen made a very different political intervention with Streets of Philadelphia, a song originally composed for the film Philadelphia and released as a single the following year. He takes on the voice of a gay man who has contracted HIV and feels himself fading away:

I was bruised and battered

I couldn’t tell what I felt

I was unrecognizable to myself

Saw my reflection in a window

And didn’t know my own face

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/21Nov_Springsteen_AE4.jpg)

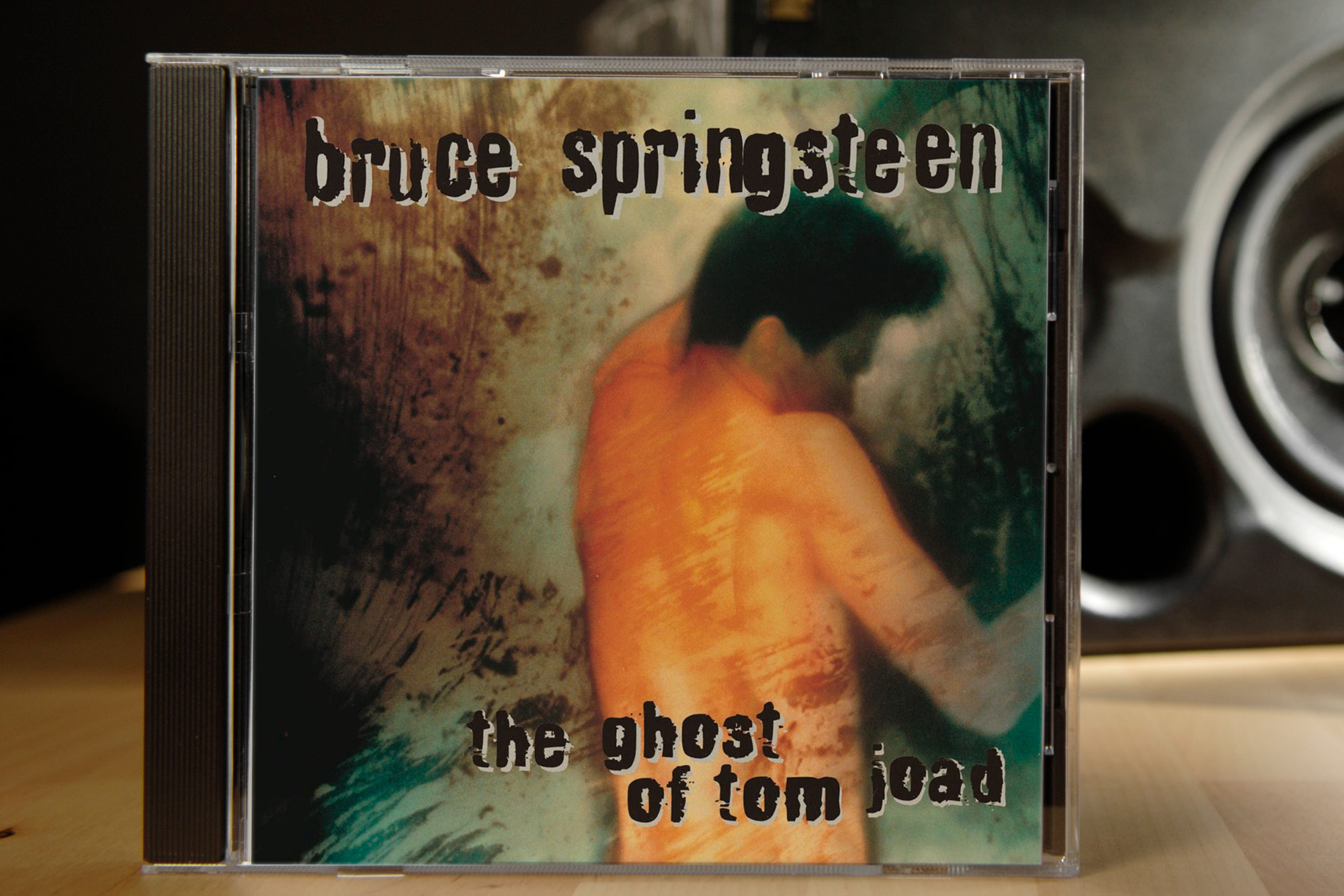

The Ghost of Tom Joad

Released in 1995, The Ghost of Tom Joad, a sparse but intense and utterly compelling acoustic record, eschewed all commercial prospects with a set of songs about the suffering of people kept out of, left behind, or crushed by the American dream. There are characters crossing the border, coming out of prison, sleeping under bridges, riding freight trains, cooking meth in a shack in the hills and taking a hit of “toncho” octane booster, to get through another night of selling sex in a cold, dark park.

These are not generally redemptive songs. People are in hard places and slipping into even harder places. They lose and then they lose more. They die the random, pointless deaths of the people who are not counted as people – run down by a car, shot dead on a muddy hill for no discernible reason.

On the title track, the first song on the album, there is a direct reference to the speech given by George HW Bush in 1991, after the expulsion of the Iraqi military from Kuwait, in which Bush heralded a “new world order.” Bush celebrated a new era that, after the Cold War, would see the United States leading, and policing, the world:

Men walking ’long the railroad tracks

Going someplace, there’s no going back

Highway patrol choppers coming up over the ridge

Hot soup on a campfire under the bridge

Shelter line stretching ’round the corner

Welcome to the new world order

Families sleeping in the cars in the southwest

No home, no job, no peace, no rest

In a nod to earlier work, Springsteen sings that “the highway is alive tonight,” but now with people moving on foot, sleeping on the roadside and trying to hold on to what they can rather than young men racing hot rods. The highway is still a powerful metaphor, only this time “nobody’s kidding nobody about where it goes.” Reprising Steinbeck’s novel, Springsteen sings of a scene at a campfire on the side of the highway where:

Preacher lights up a butt and he takes a drag

Waiting for when the last shall be first and the first shall be last.

In a cardboard box ’neath the underpass

You got a one-way ticket to the promised land

You got a hole in your belly and a gun in your hand

The song draws directly from the climactic moment in the novel when Tom, about to flee, has a final conversation with his mother:

Now Tom said, “Mom, wherever there’s a cop beating a guy

Wherever a hungry newborn baby cries

Where there’s a fight against the blood and hatred in the air

Look for me, Mom, I’ll be there

Wherever somebody’s fighting for a place to stand

Or a decent job or a helping hand

Wherever somebody’s struggling to be free

Look in their eyes, Ma, and you’ll see me”

The enduring, moving idea of Tom Joad

Youngstown is a song about a Vietnam veteran “sinkin’ down” in the former steel town where the mill is now “just scrap and rubble” and his father, a veteran of World War II, observes that “[t]hem big boys did what Hitler couldn’t do.” It’s a searing and perfectly composed song that revisits Springsteen’s long-standing concern with the workers whose lives collapsed as America deindustrialised. The characters in these songs are people like himself and the people he’d grown up with – working-class, and often implicitly white.

But on this album, a number of the songs are set in the southwest rather than the industrial cities of the northeast. The Catholic imagery is still there, but the primary female character is now Maria rather than Mary. There are characters with names like Miguel and Luis, the Rio Grande is the Río Bravo, and the border – the men policing it and the people trying to cross it – is a central theme. The idea of Tom Joad, originally a man moving from Oklahoma to California, is now entwined with people moving from Mexico across the Sonoran Desert and then across the Rio Grande and then, if they can evade la migra, the border patrol, into California.

In most of the songs that journey is a movement from one kind of suffering into another. But in Across the Border, a sublime song, a man, on the eve of an attempt at a crossing, anticipates a reunion with his lover.

I’ll dream of you, my corazón

And tomorrow my heart will be strong

And may the saint’s blessing and grace

Carry me safely into your arms

There, across the border

In 2005, Matamoros Banks, the exquisite final track on Devils and Dust, an album with important songs but lacking the thematic coherence of most of Springsteen’s work, returned to both the style and the central theme of The Ghost of Tom Joad. The song is about a poor man in car-tyre shoes, whose life slips away in the Río Bravo while he is trying to cross into Brownsville, Texas.

For two days the river keeps you down

Then you rise to the light without a sound

Past the playgrounds and empty switching yards

The turtles eat the skin from your eyes, so they lay open to the stars

Robber barons

The following year, 2016, Springsteen’s political commitment took an entirely new turn with We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, a rambunctious and joyful album of folk songs that had been performed by Pete Seeger, a communist who had sought to affirm and restore a radical tradition rooted in popular American culture. When the songs were taken on tour, Springsteen included a new folk-inflected version of The Ghost of Tom Joad.

In concert, Springsteen performs versions of other artists’ songs with an extraordinary promiscuity that ranges from Prince and The Clash to the Beatles and James Brown. Unlike any other artists playing stadium shows, he often takes requests from the audience. But he has never recorded an album of other people’s songs before or since. For an artist as deliberate and self-aware as Springsteen, the decision to seek to re-energise these songs, with their simultaneously popular and radical character, their commitment to collective solidarity and resistance, can only be seen as a carefully considered intervention into the political terrain.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/21Nov_Springsteen_AE3.jpg)

His 2012 album, Wrecking Ball, which followed the emergence of the Occupy movement the previous year, remains Springsteen’s most politically confrontational album. Death to My Hometown begins with martial drums and then the sound of a gun being cocked, followed by a direct and political statement:

Send the robber barons straight to hell

The greedy thieves who came around

And ate the flesh of everything they found

Whose crimes have gone unpunished now.

In Jack of All Trades, the song’s protagonist laments that the “banker man grows fat, the working man grows thin” while he takes what work he can find here and there:

So you use what you’ve got and you learn to make do

You take the old, you make it new

If I had me a gun, I’d find the bastards and shoot ’em on sight.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/21Nov_Springsteen_AE6.jpg)

Working with Tom Morello

But it is The Ghost of Tom Joad that has returned, again and again, as the central song in Springsteen’s political expression. The song has also acquired a life beyond its composer. It was given a new injection of life in 1997 when Rage Against the Machine, the extraordinarily sonically inventive and politically radical band that exploded out of Los Angeles in 1992, recorded their own version. It was a confrontational, furious, snarling and uncompromising attack on oppression.

In 2013 and 2014, Rage Against the Machine’s virtuosic guitarist, Tom Morello, son of a participant in the Mau Mau uprising and a committed political radical, stood in on the road for Springsteen’s rhythm guitarist, Steven van Zandt, who was recording a television series. With Morello and Springsteen sharing vocals and Morello’s crashing, soaring but still intricate guitar work, The Ghost of Tom Joad became a climactic moment in live performances – including the performance to an audience of 40 000 people in Johannesburg in February 2014.

A studio version of the collaboration with Morello was released on the High Hopes album in January 2014. This is the only time that Springsteen has released two versions of a song on two studio albums, a clear statement of his estimation of the importance the song has acquired in his body of work. High Hopes, more a collection of songs than a thematic project, also included a studio recording of American Skin (41 Shots), a song first performed live in 2000, and composed in response to the police shooting in New York of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed 23-year-old immigrant from Guinea.

It ain’t no secret (it ain’t no secret)

It ain’t no secret (it ain’t no secret)

Ain’t no secret my friend

You can get killed just for living in your American skin.

In his run of 236 performances in a New York theatre between October 2017 and June 2018, The Ghost of Tom Joad was again central to the performance. Introduced on the live recording and the Netflix show Springsteen on Broadway, with a moving affirmation of the idea of an America for all and a scornful condemnation of those in the streets and “the highest offices of our land, who want to speak to our darkest angels,” the song took on a new form and continued to accumulate cultural weight.

With the border between the US and Mexico at the centre of the bile that Donald Trump vomited across the planet, at the centre of the cruelty that he imposed on the innocent, and the figure of the migrant at the centre of the global conjuncture, there is a strong sense that, not unlike NWA’s 1988 classic, Straight Outta Compton, or Rage Against the Machine’s eponymous debut, The Ghost of Tom Joad has become more timely with the passing of time. Trump may be gone – while still refusing to concede – but the border, the people who try to cross it, the people that police it and the more than 70 million people who voted for Trump all remain.

Most attempts at ranking Springsteen’s body of work put a trinity of undeniably great albums – Darkness on the Edge of Town, Born to Run and The River – at the top. There’s always a minority who’ll make credible arguments for Nebraska and a few outliers who’ll make a case for Born in the USA or The Tunnel of Love. But 25 years down the road, there’s a solid claim for including The Ghost of Tom Joad among Springsteen’s most prescient and powerful works. DM/ ML

(Illustration by Anastasya Eliseeva)

(Illustration by Anastasya Eliseeva)