DM168 Special Report

Three Pagad vigilantes freed from jail, reviving memories of a war waged on Cape Town’s streets

Three members of People Against Gangsterism and Drugs, jailed for two decades, were freed in November, reviving memories of a group that once waged war on the streets of Cape Town. Only two long-jailed Pagad members remain incarcerated. They and others have been in and out of prison for an array of crimes, but their organisation says it’s intent on stamping out gangsterism.

First published in the Daily Maverick 168 weekly newspaper.

In the first week of November, three members of People Against Gangsterism and Drugs (Pagad), the organisation that became synonymous with vigilante-style attacks in Cape Town in the late 1990s, were released on parole after roughly two decades in jail.

The release of the trio – Ebrahim Jeneker, Abdullah Maansdorp and Moegamat Isaacs – dredged up memories of a volatile time, when South Africa was a fledgling democracy and its security structures were undergoing post-apartheid panelbeating.

Gangsters had cashed in on the upheaval and Pagad, with a predominantly Muslim membership, was formed in 1996 to counter growing criminality. The result was overlapping clashes between police, gangsters, vigilantes and, probably, intelligence operatives — mostly in Cape Town, South Africa’s gangsterism capital. A string of bomb blasts also rocked a flinching city in the late 1990s.

Jeneker, Maansdorp and Isaacs, who were sentenced to life in jail, are a notable part of Cape Town’s deeply textured gangster-versus-vigilante landscape. To some, they are simply criminals disguised as crime-fighters, but others see them as upstanding figures who fought for liberation by trying to snuff out drugs and gangs.

Their release led to some figures with ties to policing worrying that they would cause a surge in Pagad activities following a lull, or that over time others linked to organised crime would try and forge partnerships with them.

Others were simply relieved the trio was out of jail.

Pagad secretary Abieda Roberts told Daily Maverick that the three, who according to parole conditions should not speak to the media, were welcomed back into their community.

“They’ve been unjustly incarcerated and we thank them for their sacrifices,” she said.

They were among 35 Pagad members who had been through court cases and served prison terms over about two decades. Roberts said only two other Pagad members, Phadiel Orrie (sentenced in 2004 to two life terms in jail for killing a couple in witness protection four years earlier) and Faizel Samsodien (sentenced to life in jail for a 1999 murder), remained behind bars.

“Our people, from the first to the last people out, have always been model prisoners,” she said, adding that both the remaining convicts were eligible for parole. Pagad hoped the parole law would be justly applied to its members. Compared with its heyday in the 1990s, the organisation has a toned-down public profile today – but its mission has not wavered.

During the Unite For Peace march and rally from Keizersgracht to Parliament on August 27, 2019 in Cape Town, South Africa. The march, endorsed by the People Against Gangsterism And Drugs was aimed at highlighting crime. (Photo: Gallo Images / Brenton Geach)

“We’ve always said and maintained we will always stand to eradicate gangsters and drugs at all levels. People have died in this programme; people have sacrificed years in jail,” said Roberts.

Pagad was willing to work with others, including people from different religions, to tackle gangsterism, she added.

Roberts pointed out that Pagad leader Abdus Salaam Ebrahim had previously warned that if the government, community, religious and other leaders did not unite to tackle gangsters of all kinds – “political, economic and on the street” – gangs would have the upper hand.

“We are seeing it now, gangsters at the highest level,” she said.

Ebrahim has had several brushes with the law. He was jailed for public violence relating to an infamous march in the Cape Town suburb of Salt River in August 1996 that culminated in the fatal shooting and setting alight of Hard Livings gang boss Rashaad Staggie. (Rashaad’s twin brother Rashied Staggie was assassinated in the same street 23 years later, in December 2019.)

A pipe bomb was flung at Rashied Staggie’s Sea Point home at the start of January 1997, causing damage to the property. His brother, Rashaad, had been murdered in 1996. (Photo: Benny Gool)

After about nine years in jail, Ebrahim was released on parole, only to be arrested again in 2013 for a triple murder. These charges were later withdrawn. Ebrahim, according to Pagad’s Facebook page, is still very much involved with the organisation and videos of him have previously been posted on the page.

Following the release of Jeneker, Maansdorp and Isaacs, another picture of the three men – far removed from images of either crime-fighters or perpetrators – emerged.

“All three parolees, at the top of their minds, is their mothers,” Ganief Hendricks, leader of the political party Al Jama-ah, revealed. “Maansdorp is a guy who is very passionate about his mother; Jeneker feels he owes his mother a lot.”

Also at odds with images of violence was the news that Isaacs had become “a fantastic librarian” while in jail.

Hendricks said that last year the three men’s mothers had asked to see him. Jeneker’s mother, Asa Hendricks, 82, and Maansdorp’s mother, Shameema Maansdorp, 64, subsequently visited him at a constituency office in the Cape Town suburb of Athlone. Isaacs’s mother, Fawzia Isaacs, was too ill to join them.

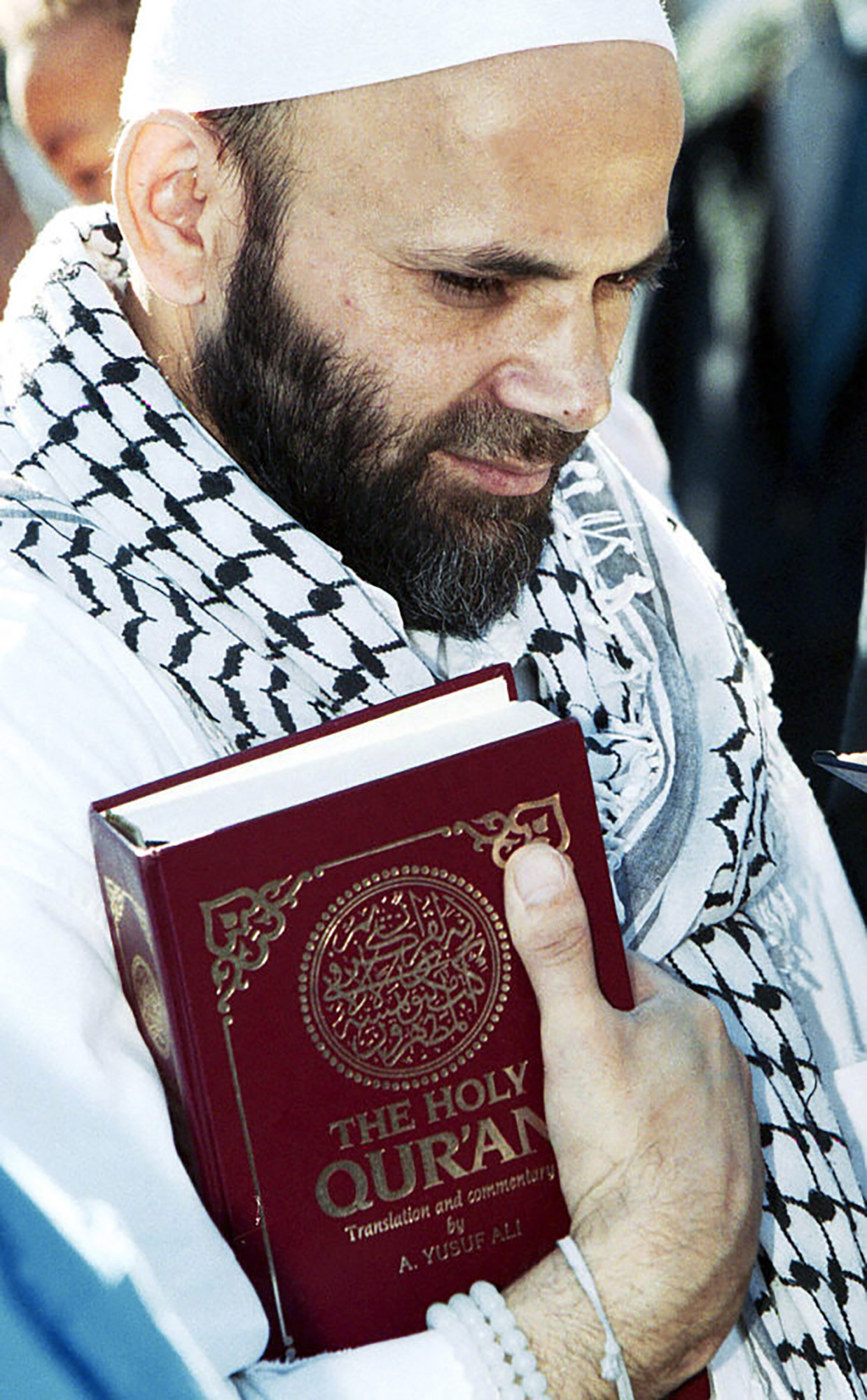

On trial: Pagad head Abdus Salaam Ebrahim was jailed for public violence. (Photo: Esa Alexander / Sunday Times)

Pagad head Abdus Salaam Ebrahim was granted parole late in 2008. Here he greets his granddaughter at his house in Lansdowne, Cape Town. (Photo: Esa Alexander / Sunday Times)

The mothers told Hendricks their sons had been eligible for parole from March 2017 and were recommended for it in March 2019. They were desperate for their boys to be released. Hendricks looked into the case, as well as the broader issue of prisoners being eligible for parole but who were still sitting in jail.

He raised these matters in Parliament. In an October 2019 letter to Justice and Correctional Services Minister Ronald Lamola, Hendricks relayed the mothers’ pleas for their sons to be freed.

Jeneker’s mother, Asa Hendricks, wrote: “I am alone, he is there [in jail], and I have no idea when he will come home. Everything at home is going backwards, I cannot sleep, and he has been too long in prison. I asked him if there’s another route we can go and he said, ‘Mama, the people in Pretoria’ [referring to correctional services officials there].”

Shameema Maansdorp said: “He is our eldest child, and we need him to take over responsibilities. My son was young when he was sentenced, he is now 40 years old. I would like him to start his own family, have children as he does not have any kids.”

Hendricks said Jeneker, Maansdorp and Isaacs had to meet several criteria before their release, including that their victims be comfortable with them being freed. The Covid-19 pandemic caused delays in the processing of their release.

A source told Daily Maverick there had been worries that the trio’s exit from prison could inspire Pagad to ramp up operations. Another said if this happened the three would distance themselves from any violence so as not to jeopardise their freedom. Media reports about court proceedings 20-odd years ago indicate that Jeneker, Maansdorp and Isaacs were involved in a complicated crime network that plagued Cape Town.

In 2002 Jeneker and Maansdorp were convicted of being involved in incidents that included a triple murder – of Adiela Davids, a suspected gangster, her daughter Feroza Marcus, and Marlene Abrahams. The three died in a shooting at a hair salon in Grassy Park in April 1999. Marcus was the wife of Americans gang boss Igshaan Marcus.

About two months after the murders, Reza Heuvel, son of a Pagad member, was shot dead in Tafelsig. Igshaan Marcus later told a court that Pagad had accused him of this shooting. Marcus was himself wounded in Hanover Park in June 1999 and Isaacs was convicted of this apparent revenge attack, in which three others were killed. (Igshaan Marcus was shot dead in October 2019 at a liquor store in Athlone.)

Jeneker was also charged with murdering police captain Bennie Lategan, who had been investigating suspected Pagad attacks, in January 1999, but was acquitted. Some of the attacks he and other Pagad members perpetrated were overt and painted the police as lax or complicit in criminality.

In September 2002, Jeneker, Isaacs and Faizel Samsodien (one of the two remaining Pagad members still in jail) escaped from the Western Cape High Court. They were apprehended the following month. That was reportedly Jeneker’s second escape from the court’s holding cells in 11 months.

The backdrop to the Pagad story is a crime pandemic across the Western Cape that involves many more people than one organisation’s members. A police fax from 1998 about “urban terrorism” said that in six months, from 1 July 1996 to the end of December that year, 39 “urban-style terror attacks” were carried out against “civilian targets” in the Western Cape.

Pagad members hold a late-night street march in the late 1990s. (Photo: Benny Gool)

The aftermath of a pipe-bomb attack in the late 1990s, Grassy Park. (Photo: Benny Gool).

In October 1997, in a massive clampdown, Operation Recoil was launched. This saw more than a thousand lawmen – sourced from the SA National Defence Force, public order policing units and detective squads (focused specifically on gangs and Pagad).

In three months, Recoil was responsible for 7,437 arrests for crimes that included murder, arson and robbery.

“Operation Recoil was initially expected to be terminated during the month of January 1998, but the violence perpetuated by the groups concerned is expected to continue in the immediate future and further measures need to be introduced in order to make stability in the area more permanent,” Parliament heard during a briefing in February 1998.

Throughout the late 1990s, Pagad was suspected of being behind a string of attacks on suspected gangsters and drug dealers, including Richard “Pot” Stemmet.

Also in 1998, Jeneker was reportedly arrested in connection with the murder of Hard Livings gangster Moeneeb “Bowtie” Abrahams, but there was insufficient evidence in this case and it disintegrated.

Hard Livings gangster Moeneeb ‘Bowtie’ Abrahams, outside his home in Giempie St, Woodstock, shortly before he was murdered in January 1998. (Photo: Benny Gool)

In 1999 the United States labelled Pagad a terrorist organisation. A US Department of State report on 1999 global terrorism patterns said Pagad and another South African organisation, Qibla, “routinely protest US policies towards the Muslim world”.

It said Pagad was suspected of being involved in two bombings – a suspected car bomb at the V&A Waterfront and the “firebombing of a US-affiliated restaurant” – in Cape Town in January that year.

“Pagad is also believed to have masterminded the bombing on 25 August [1998] of the Cape Town Planet Hollywood,” the report said.

Many rumours circulated about who was behind this bombing, including that it was orchestrated by National Intelligence Agency operatives, the police or underworld figures, but there was no evidence strong enough for court action.

This week, the US’s Terrorist Exclusion List still included Pagad on it, which basically means its members may be barred from that country. DM168

You can get your copy of DM168 at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

pagad shot themselves in the foot with the international politics and most especially the random victim bombings. They had a lot of sympathy for the anti-gang anti-drug war. One man’s vigilante terrorist is another man’s neighborhood hero.