OP-ED

Disinformation in a time of Covid-19: Weekly Trends in South Africa

A crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic creates a perfect opportunity for those who wish to cause confusion, chaos and public harm, as mis- and disinformation enable them to do just that. This week we look at the impact of disinformation on nuance.

Week25: Weekly trends — when nuance descends into simple black and white

Through the Real411, Media Monitoring Africa has been tracking disinformation trends on digital platforms since the end of March 2020. Using the Real411 platform we have analysed disinformation trends which have largely focused on Covid-19. To date, 1,039 complaints have been submitted to the platform since March 2020, 95% of which have been assessed by experts, and action taken. The past week was typified by more Covid-19 denialism, from content about masks being tools of suppression, to fake tweets used to generate conspiracy and impugn journalists.

We know that disinformation tends to simplify issues and situations that often defy simple solutions. A quick look at the misinformation put forward in the #putsouthaafricansfirst hashtag demonstrates this. Non-South African Africans are blamed for all manner of evils, from human trafficking to stealing jobs and committing crime. Leaving aside the insidious motives of those who are driving the online campaign, (see the excellent work by CABC and DFR on the people behind it) the disinformation seeks to tap into people’s existing prejudices and realities.

With our economy on the floor, unemployment skyrocketing, crimes increasing and violence spiralling, it’s understandable to seek to blame an easy target. The moment we realise just how complex something is, it makes it harder to direct anger at any one thing. On any given day, there will be expert economists, development specialists, HR practitioners, social justice activists, bankers, government officials, advisers, investment specialists, business people, entrepreneurs and more, all offering their own takes on why our unemployment is so high, and what we should be doing about it. There might be common agreement that there is an epic problem, but less agreement on its causes and how to fix it.

Many of our biggest challenges are like that – they have different causes, and there are often many possible different solutions. A side effect of disinformation is that it prevents us from seeing complex problems and instead suggests fantastical theories (like a conspiracy theory that 5G causes Covid-19) or requires simple strong solutions – we just need to get rid of the foreigners. Neither of those is helpful. Not just because they can potentially cause public harm, but because they discourage nuance. They hide the shades of grey, the possibilities of different solutions and unanticipated causes.

There is an interesting tension, because one of the roles of journalism is to take the complex (a court case for example) and help us understand what happened, what the issues are and why a court ruled in a particular fashion. To achieve understanding and explanation, good journalists are required to simplify issues. Of course, the critical difference with disinformation and journalism is that while they might both simplify complex issues, journalism does so to help us understand and make up our own minds, while disinformation usually leaves us even more confused, anxious and uncertain.

As this piece is largely about nuance, it would be silly not to add that while there is a general tendency of disinformation to simplify, identify targets and heighten fear and anger, we have had a number of complaints to Real411 of interminable videos. Usually, they take the form of a white male – speaking to the camera for anything from 12 to 50 minutes – seemingly carefully explaining, for example, how Covid-19 is a hoax.

These videos seem to be set up as a deliberate effort to suggest that understanding complex issues is too difficult. To give them a pretence at credibility they are often in an office with books behind the speaker. Why? Because we are supposed to believe that a person who speaks in front of bookcases is meant to be well read. It’s a bit like the way many adverts, for example, show people who are meant to be scientists or doctors in white coats – because nothing says this person is a scientist/doctor quite like a white coat.

The videos are tedious, as they wish to make it clear they are serious, and serious stuff must be tedious. It’s almost as if they are saying, “Look! We have our own doctor types to say Covid-19 is a hoax and here is a really long video of one of them telling you how it is. See, now you have the evidence too.”

The long video is used to help build on the myth that there is so much evidence it takes them that long just to set out their case. Want a long video of an old white man who actually does explain stuff? Try the David Attenborough series, Our Planet.

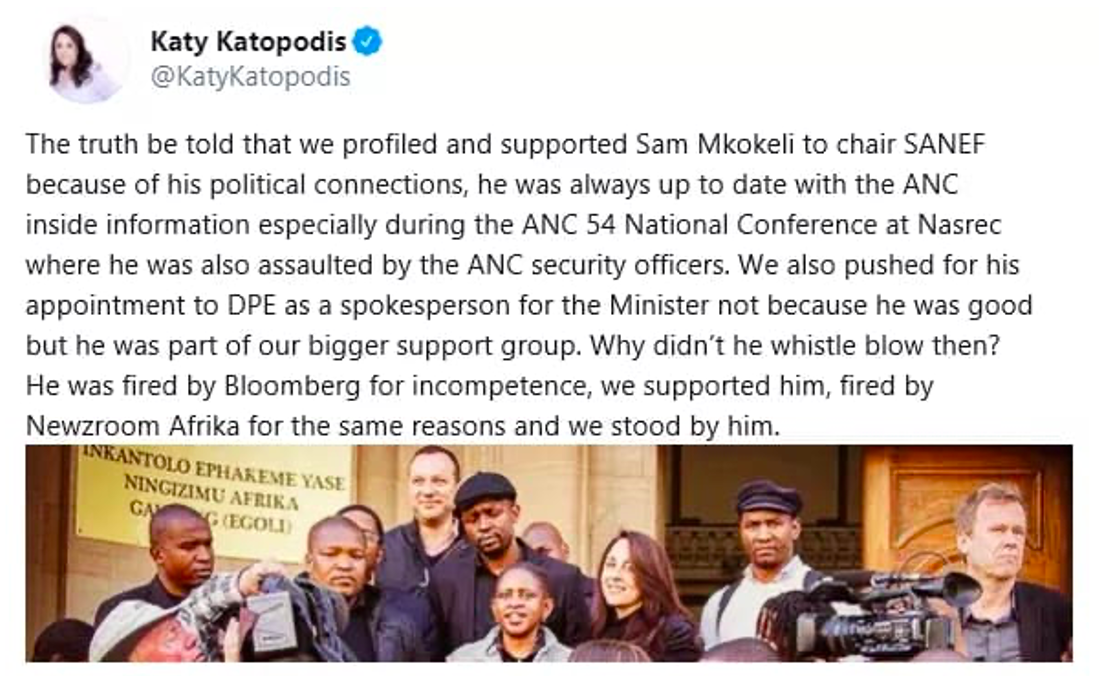

Back to black and white. This stuff matters because apart from setting up pointless binaries it also prevents us from having actual conversations about how to address some of our big challenges. Take a piece of disinformation that appeared this week about broadcast journalist/editor and SANEF Gauteng convenor Katy Katopodis. reported to Real411 here.

Her alleged “tweet” was seemingly in response to the recent furore surrounding the resignation of Sam Mkokeli, who was Pravin Gordhan’s spokesperson.

First things first. Katy Katopodis did not tweet this. To begin with, there are too many characters for a tweet – you can see that without even counting them (Jean Le Roux from DFR did and he said there are 596). Tweets are longer these days, but not a paragraph. Then, if you go to Katopodis’ Twitter handle you will see the image in the tweet was cropped from the image she uses as her background but surprise, it was cut off at the bottom to hide that the person who made this was cutting it from her profile.

Katopodis is a highly experienced journalist. If you look at her actual tweets you will see that the way she uses language is as one would expect, short sentences that each have a clear point – not a series of ideas running into one another. The other clear telltale sign that this is a piece of disinformation is that if there actually was a conspiracy and plan to place colleagues in certain places, there is no way one of the key alleged conspirators would tell us all about it in a tweet. In short, it takes no more than two minutes to see that whoever created the post is up to mischief. No self-respecting professional journalist would post this.

Why is it so bad? Aside from the fact that it impugns the integrity and professionalism of a senior editor, it fuels the conspiracy that there are groups of journalists and editors who plot how to cover issues and further the agenda of President Cyril Ramaphosa.

This prevents us from having more nuanced debates and discussions about real challenges that the journalism sector is facing. How should they deal with perceived bias? What are the implications of people leaving journalism and going to PR and vice versa? At what point is someone who was ethically compromised okay to return to the media? Or how do our media ensure quality reporting with newsrooms shrinking? What is Daily Maverick doing right, that it is expanding its coverage and has even launched a print edition?

Conspiracy theories shift these possible debates to the side. What we do know is that one of the more insidious dangers of disinformation is that it creates such a level of mistrust in credible institutions that one begins to doubt the scientific evidence presented. When dealing with doubt, it is far easier to let your emotions take over and believe information that allows you to make set conclusions without having to do too much “homework”. These days, that information is more often than not harmful, hurtful and created to cause public harm and, ultimately, detrimental to our democracy.

If you come across potential disinformation, hate speech, incitement to violence or the harassment of journalists online, please report to www.real411.org.za. If you have an iPhone you can download the app from the iTunes store (Android version coming soon). DM

William Bird is director and Thandi Smith is head of programmes at Media Monitoring Africa.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.