Investigation 168

Long road to no justice for TRC victims

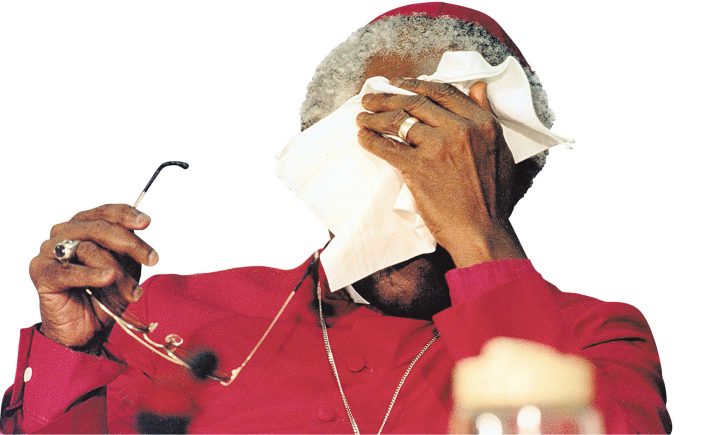

Those who suffer from amnesia, who forget the past, are doomed to repeat it, Desmond Tutu said in his address to the first gathering of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission in December 1995. In 2020, the ANC stands accused of causing enduring pain to and stealing justice from victims of apartheid-era atrocities.

First published in Daily Maverick 168.

As the families of those who suffered apartheid-era atrocities turn up the heat to see justice done at last, the tragic reality is that the ANC is largely responsible for their prolonged agony.

Some people at the highest level of ANC leadership illegally suppressed the progress to court of the post-Truth and Reconciliation Commission prosecutions of those who had been denied amnesty.

This painful saga of unconstitutional and unlawful conduct was kept secret from the families and their lawyers – and the public. Only in 2015 did the truth emerge, when Thembi Nkadimeng asked the courts to compel the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to make a decision about the murder of her sister, ANC courier Nokuthula Simelane.

In August this year Nyameka Goniwe, the widow of assassinated activist Matthew Goniwe, died at the age of 69, without seeing justice, and suffering from depression and a broken heart.

There are many more families who have endured similar unimaginable trauma.

No social compact between government and the people can survive without justice. The ANC promised justice and equality – now it’s all just shattered dreams. Today South Africa faces major problems because the ANC betrayed this trust.

Aside from society requiring that justice be seen to be done, the memory of apartheid atrocities must never be allowed to fade, nor must the stories of those brave souls who sacrificed for South Africa’s liberation ever be erased.

As TRC chairperson Archbishop Desmond Tutu said, prophetically, at the time, paraphrasing George Santayana: “Those who forget the past … are doomed to repeat it.”

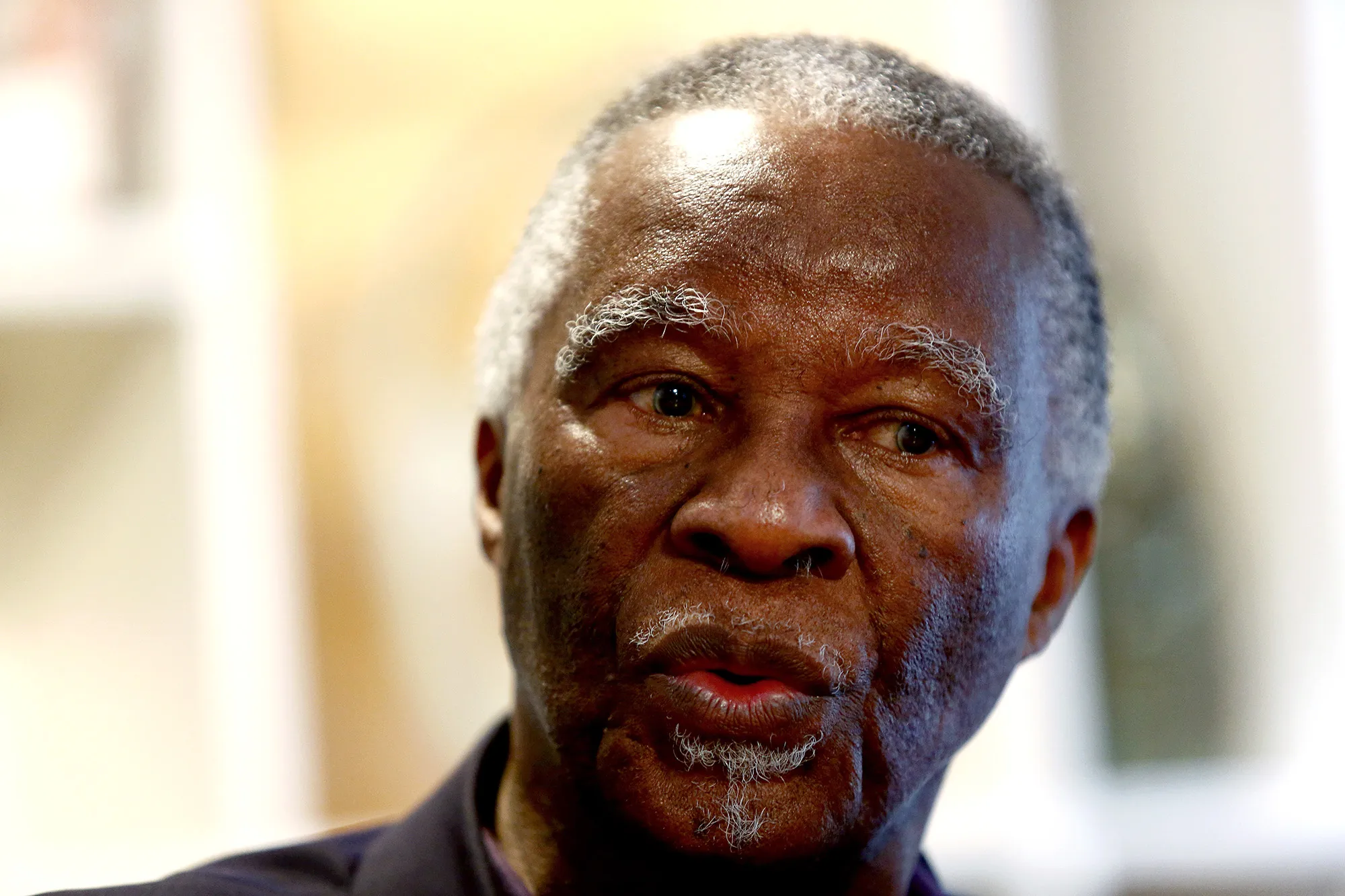

Former President, Thabo Mbeki. (Picture: Masi Losi)

After Tutu handed the final five-volume TRC Report to then-President Nelson Mandela on 31 October 1998, the public and the 21,519 victims who had made statements to the TRC about 30,384 gross human rights violations expected the government to follow up on the thousands of findings, and initiate further investigations and prosecutions of those denied amnesty.

It never happened.

Instead, five different parallel processes occurred:

- Public controversy over the report’s findings made it a political too-hot potato. Everyone feared retribution;

- The ANC and the new government secretly put political pressure on the new NPA to prevent post-TRC prosecutions;

- Similar secret pressure was applied to the SAPS, which, with the continued presence of many former apartheid police within the service, stopped and/or obstructed investigations;

- Many former security police joined the new government as an unrepentant “fifth column”;

- Apartheid-era operatives accessed the National Archives and other archives to secretly and illegally “clean” them of incriminating information.

In 2020, with a public gatvol (“sick and tired”) of mismanagement and corruption, public sentiment is growing that reconciliation cannot progress until the perpetrators of the horrors recorded in the TRC’s 3,500 pages are brought to book.

Mandela had said at the handover: “I accept the report as it is, with all its imperfections, as an aid that the TRC has given to us to help reconcile and build our nation.”

But both sides claimed prosecutions would exacerbate racial tensions. The ANC accused the TRC of trying “to criminalise the struggle” and launched an 11th-hour legal bid to stop the handover. The judge dismissed the action.

The TRC recommended that “the granting of general amnesty in whatever guise should be resisted”, and urged the NPA to “pay rigorous attention” to prosecutions.

But, in the heady, politically fraught dawn of our democracy, struggle fatigue had set in for many and public sensitivities were raw. The political tap-dance around high-profile figures, such as Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, PW Botha and Dr Mangosuthu Buthelezi, created a situation where prosecutions could be extremely divisive.

Embarrassingly, the ANC stood accused of a landmine campaign, necklacings, and torture and murder in their camps.

Meanwhile, the fledgling National Prosecting Authority (NPA), formed in 1998 as a single statutory body from a homeland mosaic, faced uphill battles from day one. It has gone through nine National Directors of Public Prosecutions (NDPPs) to date, an average of under two-and-a-half years of a designated 10-year term. All eight former NDPPs faced unlawful political pressure and interference.

South African Police Commissioner Jackie Selebi addresses the press at a conference held in Pretoria, South Africa on 12 September 2006. (Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Reg Caldecott)

The first NDPP, Bulelani Ngcuka, established a TRC component, the Human Rights Investigative Unit, which operated until 2000 but prosecuted no one.

Approximately 400 dockets were transferred to the Directorate of Special Operations (the “Scorpions”), which set up the Special National Projects Unit. It didn’t prosecute anyone.

In 2003 then-President Thabo Mbeki replaced it with the Priority Crimes Litigation Unit (PCLU), mandated to deal with TRC cases, now deemed “priority crimes”. It was headed by Advocate Anton Ackermann with deputy Advocate Chris Macadam from the Scorpions.

About 150 cases would be immediately investigated. Imtiaz Cajee, nephew of Ahmed Timol, requested that Macadam and the PCLU investigate Timol’s death in detention. But it would take decades just to reopen the Timol inquest (the first one was in 1972).

When the NPA met the Scorpions, DSO Special Director Adv MG Ledwaba said the Scorpions would not investigate, SAPS must do that. SAPS said it was not their responsibility. It created an investigative dead end.

Then all the TRC cases were suppressed, allegedly awaiting “policy formation”. At a February 2004 meeting of all the Director-Generals, chaired by Adv Vusi Pikoli, then-DG of the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (DoJ), a secret “Amnesty Task Team” was appointed to see how to avoid prosecutions and guarantee immunity for apartheid-era criminals. This would become an amendment to Prosecution Policy.

In May 2004, Ngcuka “declined to prosecute” the “ANC 37” in connection with “conflicts of the past”. Two months later Ngcuka resigned, following his scandalous 2003 decision not to prosecute Jacob Zuma.

Acting NDPP Dr Silas Ramaite now decided to prosecute three security police officers for the 1989 poisoning and attempted murder of the Rev Frank Chikane. Ackermann was about to arrest the three cops responsible when the suspects’ attorney, Jan Wagener, phoned him and said Ackermann would shortly get a call from the DoJ to stop him. That call came within minutes.

Shocked, Ackermann refused to take an order from a DoJ official. His own boss, Ramaite, then instructed him to withdraw. The Chikane plea bargain ended in 2007 with former Justice Minister Adriaan Vlok and former SAP Commissioner Johan van der Merwe each being sentenced to 10 years’ jail, wholly suspended for five years.

The NPA then successfully prosecuted an ANC member implicated in the mob killing of two people in 1985. But only three cases were ever finalised out of the 400. Ramaite then placed a moratorium on all TRC cases.

Pikoli replaced Ramaite as NDPP on 1 February 2005. The new “guidelines” stipulated that the Task Team, comprising senior officials from the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), SAPS, the Scorpions, and the DoJ would “assist the PCLU” – but behind closed doors. The NPA would retain the final decision. But the other parties misunderstood their roles and tried to influence the NPA, mandated to prosecute “without fear, favour or prejudice”.

In early 2006, Ackermann had five TRC cases ready, and another 11 cases as “major priorities” for 2006-07, but NIA and SAPS reneged on promised “assistance”. SAPS Commissioner Jackie Selebi objected to Ackermann’s involvement as leader of the TRC prosecutions, claiming he wanted to put ANC leaders on trial.

Ackermann had realised no investigation or prosecution could occur in the political context that prevailed when the Task Team “closed” the Timol matter in November 2006 without investigating. He believed the amended guidelines were unconstitutional. Two years later Judge Frans Legodi struck them down.

Mbeki then made a fatal mistake. He pressured Pikoli about the TRC cases, trying to protect comrades-in-arms and Selebi, about to be arrested on unrelated corruption charges.

Pikoli stood firm, so Mbeki suspended him on 23 September 2007 and instituted an inquiry into his “fitness to hold office”, chaired by former Speaker Frene Ginwala. Acting NDPP Mphe removed Ackermann from the TRC cases.

Pikoli then dropped a bombshell.

He told Ginwala in an explosive affidavit that “political interference” had had a “serious impact on the pursuit of the TRC cases by the NPA”. In a later affidavit,

Pikoli explained how politicians had turned the screws.

In 2006, Ministers Zola Skweyiya, Thoko Didiza, Mosiuoa Lekota, and Charles Nqakula had summoned him to a meeting that was never made public. Also present were Selebi and Loyiso Jafta, Chief Director in the Presidency. Pikoli’s boss, Brigitte Mabandla, was apparently “indisposed”.

“It became clear to me that powerful elements within government structures were determined to impose their will on my prosecutorial decisions. … there was a fear that cases like the Chikane matter could open the door to prosecutions of ANC members,” Pikoli said.

For guidance, Pikoli approached Minister Mabandla, meeting her on 6 February 2007. She then accused him in a letter of having given her the impression that he would not pursue apartheid-era cases.

Pikoli retorts: “I am at a loss to explain how the Minister reached such a conclusion. … [It was] unwarranted interference in my constitutional duty.”

So Pikoli prepared for Mabandla a detailed secret internal memo dated 15 February 2007, setting out the history and problems around the TRC cases, including his perception that his independence had been undermined. Mabandla failed to respond.

Pikoli said further in his affidavit that: “It would appear that there is a general expectation on the part of the Department … SAPS and NIA that there will be no prosecutions and that I must play along. My conscience and oath of office that I took does not allow that,” he said, adding later that as their behaviour pointed to unlawful and unconstitutional conduct, it would be in the public interest to release the secret memo.

After the Chikane judgment, the newspaper Rapport used a fabricated document in a story claiming the NPA was about to prosecute ANC leaders. The ANC panicked. Pikoli was hastily summoned to a “showdown meeting” on 23 August 2007, attended by (among others) Selebi, National Intelligence boss Ronnie Kasrils, Mabandla, Skweyiya and several DGs.

It was a stormy, adrenalin-charged meeting of high drama.

An angry Selebi told him: “The gloves are now off,” and he was “declaring war” on Pikoli, threatening the NDPP – with the acquiescence of the senior government officials and ministers present.

In November 2008, Frene Ginwala found that the government could not substantiate Pikoli’s suspension. A month later the Prosecutorial Guidelines changes were struck down. Then the Task Team fell apart, the Scorpions were disbanded and SAPS withdrew. Macadam took over but SAPS referred him to Commissioner Anwa Dramat, head of the (new) DPCI or Hawks, who refused to meet with Macadam. Deadlock. Again.

In 2009, the High Court ruled an amnesty committee be convened to rehear the PEBCO 3 matter, but the NPA provisionally withdrew the prosecution. The PEBCO 3 case had begun in 2004, but DoJ mysteriously had failed to file court papers, delaying the case.

And that was where things stood as the country struggled through Zuma’s “wasted years”. Families, civil society groups, lawyers and activists tried to force progress in investigations, to get prosecutorial decisions made or finalise cases. During this time, Nomgcobo Jiba was acting NDPP for a year. Adv Mxolisi Nxasana was appointed NDPP in August 2013, and Macadam replaced as head of the PCLU by Adv Shaun Abrahams.

By 2015 the families’ efforts were gathering steam. Nokuthula Simelane’s sister asked the High Court to force SAPS to finalise their investigation and compel the NDPP to make a prosecutorial decision or refer the case to an inquest. Neither the NPA nor SAPS filed answering affidavits, nor did they dispute Pikoli and Ackermann’s affidavits asserting “gross political interference”.

Pikoli concluded an affidavit in the Simelane matter with these words: “It is no coincidence that there has not been a single prosecution of any TRC matter since my suspension and the removal of the TRC cases from Advocate Ackermann.

“The political interference or meddling that I have set out in this affidavit is deeply offensive to the rule of law and any notion of independent prosecutions under the Constitution. It explains why the TRC cases have not been pursued. It also explains why the disappearance and murder of Nokuthula Simelane was never investigated with any vigour and why the pleas of her family and her representatives were ignored.”

In March 2016 four men were charged with Simelane’s murder, but by 2019, one policeman had died. In January 2016 the Timol family had given the NPA new evidence and had to threaten litigation to get the inquests into the deaths of detainees Ahmed Timol and Neil Aggett reopened. The NPA and police had provided no help to the families, who had been helped in the investigative work by the Foundation for Human Rights (FHR) and pro bono attorneys from Webber Wentzel and Cliff Decker Hofmeyr, and pro bono lead counsel Howard Varney. The cases inched forward.

Meanwhile, the horrified nation watched mass looting and corruption as Zuma-style patronage extended to every level of government, including the hollowing-out of the NPA. Despite this, the Timol Inquest reopened in June 2017, and in October found that the police had murdered Timol.

Former security policeman Joao “Jan” Rodrigues was the only surviving policeman who had been present when Timol was murdered. Following the inquest finding, he applied for a permanent stay of prosecution.

Macadam made an affidavit in November 2018 in the Rodrigues matter, in which he admitted there had been political interference, but the NPA held it back, only filing it to the court on 4 February 2019, drawing the court’s ire for “deliberately withholding” it.

It was only at this point that the NPA – for the first time – finally admitted publicly that there had been unlawful political interference. Meanwhile, earlier in 2018, a further 20 TRC cases had been placed before the NPA and Hawks.

Towards the end of 2019, lawyers for the families threatened the Minister of Justice with an urgent High Court application if he did not instruct the courts to reopen inquests into Neil Aggett and Dr Hoosen Haffejee. On 16 August 2019, the Minister of Justice announced that the inquests would be reopened.

The door was finally creaking open. But how many documents have been destroyed or gone missing? With more than 400 TRC cases originally, there is still a long way to go. How many suspects or witnesses will die before their turn in court?

On 5 February 2019 a group of former TRC commissioners wrote to President Cyril Ramaphosa requesting an apology to the victims and the appointment of a commission of inquiry into the political interference that has suppressed the TRC cases. The Presidency failed to respond. Yes, you read that right.

Perhaps the last word should go to Judge Billy Mothle who, in his judgment in the Timol case, said: “Importantly, this case reaffirms that justice and the truth were never meant to be compromised during all that our young society sought to do in dealing with its troubled, turbulent and shameful past.”

Justice will come. Eventually. Will it be too late? DM168

David Forbes S.A.S.C. (Ret) is a self-taught workalone, multi-award-winning South African director and producer honed by his training as a cinematographer and his earlier work as a photographer, journalist and newspaper sub-editor.

You can get your copy of DM168 at these Pick n Pay stores.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.