MATTERS OF OBSESSION

So you think you can Rumba?

A behind-the-scenes peek into the misunderstood, notoriously underestimated lovechild of the sport and art industry and how cut-throat competitions like South Africa’s historically prestigious ‘Rumba in the Jungle’ held the key to the door of opportunity for many a generation.

From the weightlessness of the Viennese waltz, to the passion of the Argentine tango, dancesport is arguably the love-language of the sport industry. The sport has a longstanding, intricate history in South Africa that stems long before the country’s first national ballroom competition took place in 1928.

During the socio-politically tumultuous time in the era of apartheid, a system of segregation existed between black and white dance associations.

“With separation being entrenched in the Population Registration Act, Group Areas Act, Separate Amenities Act, Immorality Act and a plethora of other racially based pieces of legislation in the 1950s, the social – and competitive – dance floor remained divided along black and white lines,” notes researcher in the Department Historical and Heritage Studies at the University of Pretoria, Alida Green in her 2009 paper, “Passionate competitors: the foundation of competitive ballroom dancing in South Africa (1920s-1930s)”.

Yet, because of its very essence, dance represented – and still represents – an expressive language and culture that gave people hope.

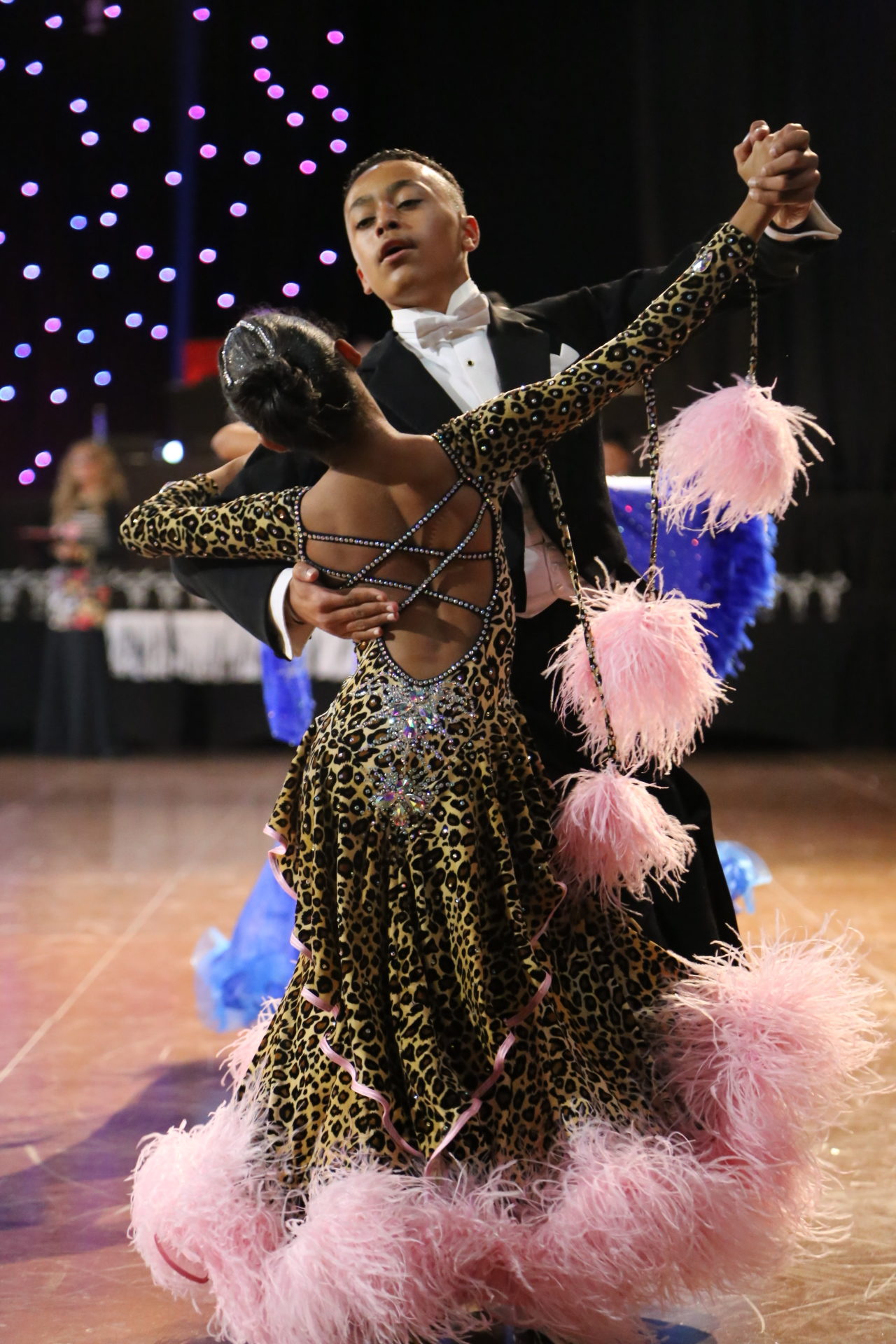

Victor Fung and Anastasia Muravyeva; Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

Victor Fung and Anastasia Muravyeva; Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

“During the apartheid years, ballroom dancing was seen as an escape from poverty where during a few hours of the week, ballroom dancers could dance like ‘kings and queens’,” says author S. Dalton, in his 2000 book, Ritmes, passies en swier.

After the demise of apartheid, and socio-political reform within the industry, dance was rated the third most popular leisure activity next to soccer and boxing in South Africa in the late 1990s according to Dalton, and the dancesport landscape was arguably in its prime. One competition stood out on calendars as the pinnacle of the professional dance year of local and international professional dancers and tourists alike – the Rumba in the Jungle International Dance Championships (RITJ).

Born in 1981, RITJ was South Africa’s first international Ballroom and Latin American dance competition established in the old Bophuthatswana homeland (now North West Province). The competition ran for 37 years consecutively at the Sun City luxury resort and by 1998, RITJ went down in history as the premiere international dance competition in Africa growing from hosting six, to 32 countries with over 2000 dance competitors at an international level.

Rumblings in the jungle

By 1999, however, internal conflicts began to hamstring the dance fraternity. As noted by Green in a 2008 paper, “Dancing in Borrowed Shoes: A History of Ballroom Dancing in South Africa (1600s-1940s)“, differences between members of two of South Africa’s biggest dance councils and organisers of the event at the time, the Federation of DanceSport South Africa (FEDANSA) and the South African National Council of Ballroom Dancing (SANCBD) started to form when several directors of the joint company, DanceSport South Africa (DSSA), refused to relinquish their positions following national elections for new office bearers of the SANCBD and FEDANSA.

Following the disagreements and a court case in 2004, dancesport started to receive fewer sponsorships and the support it had enjoyed before the turn of the century slowly decreased.

Dancesport had come down hard from an immense high losing its popular standing as one of the sports of choice in South Africa and in 1999 one of the most prestigious international festivals of the dancesport (RITJ) world disappeared and would remain absent for 18 years.

“Dancesport remained quietly popular after RITJ disappeared but the industry itself did not disappear altogether. Dancesport was already recognised by the IOC as a potential Olympic discipline. People kept their studios running. Most or all studios are privately run,” says Sema.

‘Rumba in the Jungle’: The Return

In September 2017, when Cape Town-based film producer Dominique Jossie discovered that a filming job she had been booked to do was the resurgence of the historically prestigious international dance competition, RITJ, after nearly two decades of lying dormant, she called friend and director Yolanda Keabetswe Mogatusi and the duo got to work on a rare opportunity to capture the historical moment unfold in the dance world.

“The competition’s atmosphere is bursting at the seams with excitement. The tension is so heady that it feels as if you could reach out and touch it”.

Jossie and Mogatusi hail from competitive dance backgrounds – Jossie from ballroom dancing and Mogatusi from ballet – and the documentary was in part inspired by a dream they had both left behind but still lived vicariously through the dancers they filmed.

“As a child, I was inspired by Rumba in the Jungle. I really believed I was going to become the first prima ballerina from Soweto. I used to block out time every Saturday to watch dancers float around the floor in beautiful dresses at the annual competition on TV. Dominique and I agreed that the return of the historically revered competition was a moment that deserved the spotlight and so the documentary concept was born,” says Mogatusi.

After going through boxes of archived footage, intense research and an excruciating nine-month, post-production gestation period, Jossie and Mogatusi in association with Screendance Africa and 1000 Hugs Films, gave birth to Rumba in the Jungle: The Return, an immersive snapshot of the resurgence of the four-day dance festival and capturing the essence of the cut-throat intensity of the dancesport industry and the atmosphere leading up to judgement day.

“The competition’s atmosphere is bursting at the seams with excitement. The tension is so heady that it feels as if you could reach out and touch it. There are dance workshops run by experts in the field and dancers from all over the country, some from really disadvantaged, poor areas in the North West who have done everything they can to get there. We chatted to a mother who had gone door to door in her town requesting donations to get her daughter to a big dance championship in Paris where she had qualified to compete,” says Jossie.

Rumba in the Jungle: The Return also follows the dancesport industry’s multiaward-winning champion-come-legends, like Tebogo Kgobokoe and Michael Wentink passing their dance shoes on to the next generation.

“Winners are simply willing to do what losers won’t.” – Million Dollar Baby, 2004

Multi Award-winning professional South African ballroom dancer and specialist in International Style Latin, Wentink embarked on his professional dance journey in 1978 at the age of seven.

“The minute a piece of music came on, I couldn’t help myself. I just burst into an amalgamation of dance energy. And the funny thing is, my parents and I never knew where I learned it from, I just felt the music,” says Wentink.

In the 1970s, ballroom and Latin American dancing were not on the map in South Africa but Wentink’s parents realised their son needed to express himself through movement. Dance cult films Grease and Saturday Night Fever had just been released and inspired Wentink’s parents to enroll him in disco dance classes.

“Categories in competitions for children were virtually non-existent back then. But now the children’s category is impacting dance more than high-level competitive dancing ever did. A competition is run and will only be successful based on two things: the children’s category and Pro-Am (professional-amateur) – very wealthy ladies who choose top professionals to compete with. Instead of paying a once-off entry fee like everyone else, they pay per dance. It is not uncommon for a competition or venue to be sponsored by Pro-Am ladies.”

Bothlale Sehoole; Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

Kisha Brown and Curtley Klassen; Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

Kisha Brown and Curtley Klassen; Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

Kisha Brown and Curtley Klassen; Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

Image from “Rumba in the Jungle, the Return” (supplied)

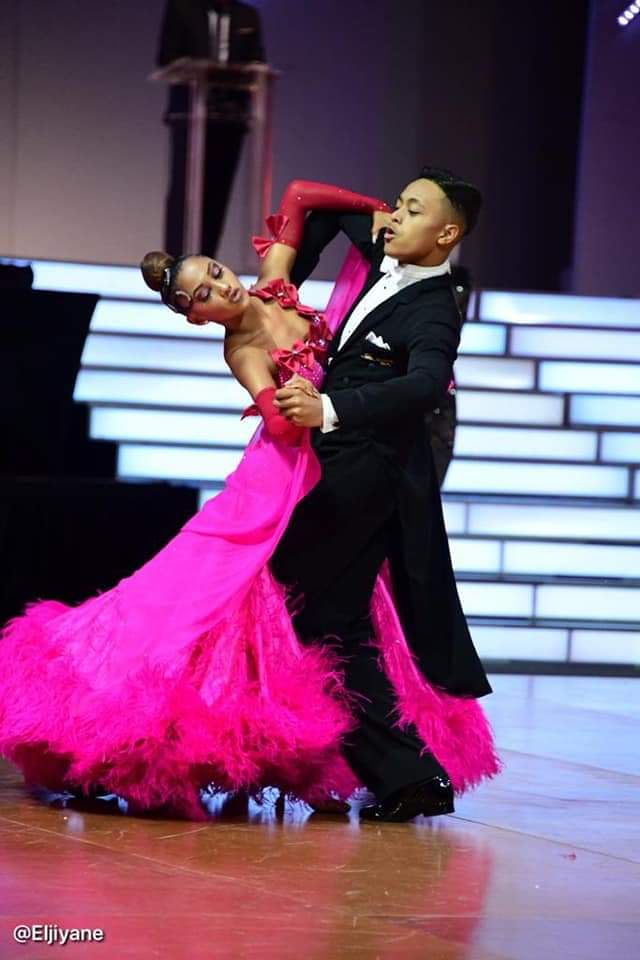

Image supplied (@Eljiyane)

Over the past decade, solo ballroom and Latin became popular among children dancers.

“Two years ago I was judging a competition in Naples where a four-year-old girl was dancing latin in the solo category and I was dumbfounded. These days the competition is basically reliant on children’s entries,” Wentink says, as he imparts his dance skills and knowledge on to the new generation of potential dance champions.

Former Junior (U16) and current Youth (U21) Ballroom and Latin champions, Kisha Brown and Curley Klassen from Ennerdale, Gauteng, feature in Jossie’s and Mogatusi’s feature documentary bagging first place in their age group in Rumba in the Jungle 2017.

The pair started dancing eight years ago – Brown was eight and Klassen nine. They are currently training under former Strictly Come Dancing, South Africa judge, Tyrone Watkins. Brown and Klassen estimate they have done over 240 competitions to date and taken South African colours at the South African Championships for the past five years. Brown and Klassen did additional private lessons with Wentink for competition preparation.

“We all feel like we deserve to win. We’ve put in the effort and feel we’ve worked harder than the next dancer. It’s all smiles until we step onto the dance floor. Then, it’s game time.”

“The dance industry is glamorous but extremely competitive,” say Brown and Klassen. “When we walk onto the dance floor at a competition, getting ready to dance, the only thing I am worried about is falling on my face or having a ‘dress malfunction’!” says Brown.

Brown and Klassen say the most challenging part of what they do is “balancing their schoolwork and training, keeping fit and finding the right dance outfits” – as 2018 South African Amateur Latin Champion Modibana Masipa from Pretoria can attest to.

Following in her father’s footsteps, Masipa began dancing at the age of ten and has been dancing for the past 15 years. Masipa trains six days a week and takes two to three hours out of her own time to run through her routines.

“The dancesport industry is very competitive. We all feel like we deserve to win. We’ve put in the effort and feel we’ve worked harder than the next dancer. It’s all smiles until we step onto the dance floor. Then, it’s game time. The three most competitive competitions in South Africa at the moment are The Super Series (three per year around the country), Rumba in the Jungle and, of course, the National Championships where you can earn your colours,” says Masipa.

“I have done many competitions since my first one in 2006 and my favourite has to be ‘Rumba in the Jungle 2017’ and the ‘World Championships in Paris 2017’. That year was just incredible.”

Dancesport is not a cheap affair and some of the most common challenges expressed among the dance fraternity are the crippling costs.

“Because a substantial part of your final score is based on presentation, Latin dancing can get very expensive. A pair of shoes and a dress for a competition can easily cost you R5,000. And at times you’re required to have a second or even third ‘look’. Dance shoes get worn out so easily if you’re training regularly. Going through two pairs a year costing about R1,400 each, adds up. Then there’s the matter of hair and makeup. Weekly, my lessons are over R1,500, which can increase depending on where we are in the season. The closer we are to a big competition, the more lessons you want to have to make sure that your coach gets you ready for the dance floor and make sure that you’re dancing at your optimum. That’s why it’s such a big commitment. You need to have clear goals for yourself so that it doesn’t feel like you’re simply flushing money down the toilet,” says Masipa.

Take a bow

Michael Wentink and dance partner for 10 years, Beata Onefater’s approach to dance was classed in the media as being “ahead of its time” and “unconventional” and it always turned heads. In the early 2000s, the pair would stun the audience in electric-blue costumes, skin-tight zebra-print pants and move like they were on fast-forward – Wentink’s form as tight as a corkscrew.

“I would do unconventional things like dance the paso doble to club music, employing a gymnastic ribbon as my ‘cape’. I never did those things because I wanted to shock, or be different, I did those things because I understood that to set myself apart I had to be fearless in experimentation. In a tremendously cut-throat industry like dance, you have to stay true to yourself and you have to believe you,” says Wentink.

Wentink and Onefater went on to hold their position as part of the top six in the world for the 10 years they danced together and were the only couple in the country’s history to win 44 out of 45 first titles for South Africa. In 14 years, this record remains untouched.

“People called us ‘the legend couple’ and I attribute this to a few things. I never watched and still don’t watch dance videos to learn moves. I watch fashion and music videos. I draw inspiration for crafting a new move from how a piece of fabric moves or falls on a catwalk model. I draw inspiration from a mood, from music and from feeling,” says Wentink

Wentink regards his ‘retirement’ as one of the hardest points in his career. It took him nearly 10 years to process that his time in the spotlight with Onefater had concluded.

“Our [Beata and Michael] partnership was one of the most special things to me. I felt that I wanted to be remembered as being the best at what we did when we did it. We were approaching what we in the dance fraternity call a ‘dead-man’s-shoes’ phase which is when a couple is on the brink of retirement and gets knocked out by the younger generation. I wanted to keep the sparkling chandelier that was our experience, intact,” says Wentink.

“The day I stop learning, the day I stop being able to give something new to the dance world – not what I did 14 years ago but the vision of dance in 14 years’ time – that is the day I take my final bow”.

Although studies are thin, dance in South Africa continues to play a significant role socially, politically and culturally, as leading cultural historian Peter Burke once wrote: “Dance history, once the province of specialists, is now taken seriously by cultural historians and discussed in relation to politics and society.”

“I think we have moved into a whole new generation of style and priority. We have evolved so much in Latin and ballroom that we don’t look like we’re doing Latin and ballroom anymore. It has become more contemporary. Yes, we still have the fundamentals like the beats, the beat values, the rhythms, but it has become so ‘art decor’ and it is a good thing because it means dancesport is still ‘moving’. Evolution and adaptability indicates that the ‘organism’ is still very much alive.

“There is a new generation of dancers who are as hungry as little tigers waiting for their next meal. The day I stop learning, the day I stop being able to give something new to the dance world – not what I did 14 years ago but the vision of dance in 14 years’ time – that is the day I take my final bow,” says Wentink.

“Dance is that one thing that no one cannot take away from me. No matter what. I’ll forever be a dancer. On and off the floor. My dancing belongs to me. When I walk onto the dance floor, I’m thinking of all the effort it took me to get to this point. I put in so much hard work for that very moment. It’s make or break time. I do my absolute best and leave it all on the dance floor with no regrets,” says Masipa.

RITJ returned in 2018 and 2019 with a turnout of over 1,500 dancers and over 3,600 visitors. Says Frans Sema: “Dance is one of the universal languages that will remain relevant to the world.”

Due to Covid-19, this year’s competition was cancelled, but is set to return in 2021. Rumba in the Jungle: The Return is in its launch phase. TikTok and other online competitions have been opened to the public to keep the spirit of dance alive.

“My hope is that the film comes as a vestige of inspiration and hope for dancers all over South Africa and to give them something to look forward to in the new year,” says Jossie. DM/ ML/ MC

For more information onRumba in the Jungle: The Return, visit http://www.rumbainthejunglefilm.com/

Leading up to its official release to the public at the end of November (date to be confirmed) the film will be hosting a series of dance competitions, one being a TikTok dance challenge.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.