OP-ED

Life after Donald Trump: Facing the final frontier

Donald Trump’s wall between the US and Mexico was always going to be the imaginary frontier invoked throughout history – the point was never to actually build ‘the wall’, but constantly to announce its building. It’s the constant threat of invasion or internal subversion that keeps people in line, a tactic fruitfully exploited by the National Party in South Africa and autocrats almost everywhere.

As Donald Trump faces having to quit the White House, either voluntarily or under escort (but still furiously tweeting “foul”), one key to understanding the mayhem he leaves behind is that in four years he has slammed shut one gate on American optimism. Trump’s unfulfilled rhetoric of building a big, “beautiful” border wall effectively sealed off the centuries-long ideal of an endless frontier: a dream or aspiration, however illusory, which always promised fresh horizons.

Inciting crowds to chant “Build the wall!” convinced legions of Americans that only Trump’s promised barrier could halt an army of drug smugglers, murderers and rapists from flooding into the United States. In fact, “America First” really meant looking inward, rather than outward. In the domestic trauma habitually evoked by Trump, the barbarians weren’t just trying to cross the Rio Grande en masse, the enemy was also within: liberals, the media, civil rights campaigners, Black Lives Matter protesters, scientists, Democrats. The list grew ever longer.

Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again” projected a dystopian nightmare: the “swamp” of Washington politics, corrupt officials, biased judges, incompetents in charge of the CIA and FBI, etc. Beyond the delinquency of Donald Trump, however, the recent profusion of conspiracy theories heralds a massive loss of faith, marking the end of that imaginary frontier and hastening the decline of America’s imperial role in world affairs.

The Pulitzer prize-winning scholar, Greg Grandin, points out that frontiers created by fighting wars and opening markets simultaneously represented “a gate of escape”, helping to deflect internal social problems outward. Today the key question is: What happens when the frontier comes to a halt, leaving no more room to expand and so nowhere else to escape? This is true for former European colonial powers and consequently, belatedly, for South Africa too.

Last month the Department of Public Works proposed to the parliamentary public works portfolio committee the expenditure of R5-billion (at least) to rebuild large sections of the border fence, including sensors, cameras and drones, as a barrier with four neighbouring countries (eSwatini, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Lesotho). This comes after the corruption-plagued scandal of R37-million spent on the Beit Bridge border fence which critics claim is little more than a washing line. The official making that parliamentary presentation sounded an ominous Trump-like alarm about the need to fence us off from our neighbours. “We are not safe socially, politically and economically,” he warned. “In terms of war, we are fragile in a way that anyone can come to South Africa.”

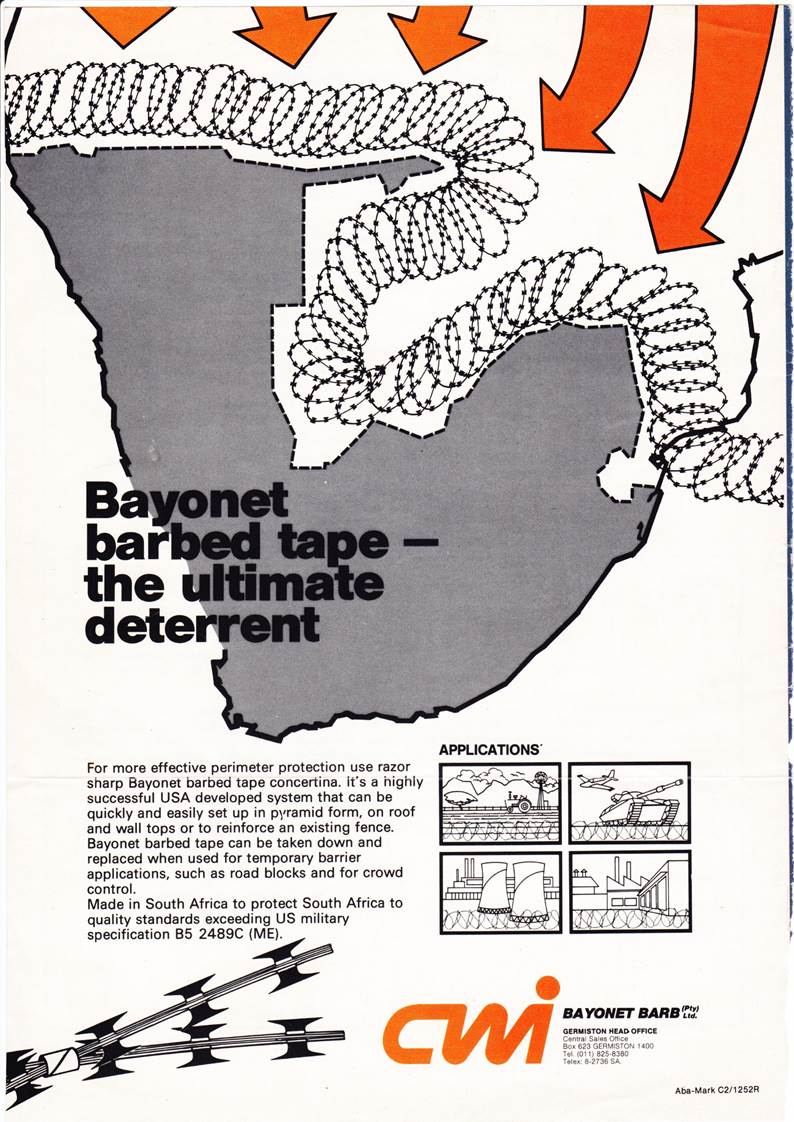

This is remarkably similar to a grim illustration 37 years ago in the military journal, Security Focus, showing massive coils of “bayonet” razor wire stretching from the coast of Namibia, across the northern border of South Africa and trailing out into the sea beyond Mozambique. That was the era of the border war and PW Botha’s “Total Onslaught.” The advert boasts, “Made in South Africa to protect South Africa to quality standards exceeding US military specification.”

Clearly, there are still bureaucrats, or what used to be called securocrats, as well as politicians peddling xenophobic alarms, still trying to put the frighteners on us by trumpeting that the barbarians are at our gate.

In his book, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (2020), Grandin locates the many social crises currently facing the United States in the inability to export problems any more. What’s happening in the US and the former European colonial powers can also be heard in South Africa: the squawking of some extremely angry chickens coming home to roost with a much-delayed vengeance. The solution can no longer be found via a constantly shifting frontier (the acquisition of more land and mineral wealth), but in dealing with domestic dilemmas left in the wake of that centuries-long process; social and economic problems which piled up, unresolved, and so finally have to be confronted in the 21st century.

The same perhaps could be said of Britain, whose frontiers once reached across a quarter of the globe. But national horizons have shrunk dramatically, ending in Brexit. Up to a century ago Europe collectively saw many millions of their citizens emigrate. Yet those same countries are now vigorously trying to prevent far small numbers of immigrants, usually from their former colonies, fleeing the fallout from imperial ventures: chaos, poverty and sectarian wars.

In South Africa, more than 250 years of expanding colonial frontiers has now bequeathed us with the highly emotive hullabaloo over land.

At the heart of colonialism is the frontier; a malleable and (imagined) limitless frontier. For European powers – Portuguese, Spanish, British and French – their frontiers were mostly at the other ends of the earth: in South America, the South Seas, Australia, Asia or Africa. Those frontiers were fluid and opportunistic. They were driven both by a “going forward” and a constant “fleeing from” (urban poverty, unemployment, religious persecution).

Here, in the most fervent of our current disputes over land and the legacy of colonialism, disagreements tend to separate neatly into race. The fact is that we are still mired in fighting over our deeply unsettled past. In his book, The Café de Move-on Blues (2018), the writer Christopher Hope gives a sardonic account of an extensive trek around the country, after which he concludes: “A quarter of a century into the new democracy, I found race and colour to be more divisive than ever. The war of words had never felt more violent.” Hope begins by observing dryly: “It’s not often you watch an angry crowd lynching a statue.” By chance he was present on the autumn morning in 2015 that the statue of Cecil Rhodes was removed from its plinth at the University of Cape Town.

Inevitably, although describing the present, what he actually records are the ghosts of old that still hound us. “South African history is difficult to explore as a chronicle of past events because it is more like analysing a crime scene,” observed Hope. “There are cover-ups, frightened witnesses, tainted evidence, and testimonies are riddled with subterfuge and deception.” Later, he remarks that “historical analysis is very often war by other means”.

The opposing, deeply entrenched beliefs exposed by the “Rhodes Must Fall” uproar, for example, revealed that we still mostly prefer our history in black and white, reluctant to concede the legitimacy of other viewpoints or heed new information. Professor Christopher Saunders, in his seminal book The Making of the South African Past, charts the shifting interpretations as well as the conflicting reassessments of leading historians. Saunders recalls: “In 1853, the missionary David Livingstone criticised what he called the ‘Van Riebeeck Principle’, the idea that whites were always right and had the right to dominate and subjugate others.” Over a century and a half later, during the impassioned debates over colonialism, it seemed that quite a few white South Africans had not progressed much beyond Livingstone’s “Van Riebeeck Principle”.

Once again our past, in the bronze likenesses of dead white men, became a battlefield for the present. It was a proxy war. The iconoclasts (mostly black) wished to tear down such graven images, while the iconophiles (mostly white) defensively vouched for – and even venerated – those images. Three decades previously in White Boy Running, a classic account of life under the old regime, Hope remarked that “It is always yesterday in South Africa.”

In South Africa the colonial frontier expanded relentlessly, systematically stripping indigenous peoples of land, traditions, pride and dignity. Apartheid launched further assaults while also conducting a final frenzy of remapping. The borders of South Africa had been fixed in 1910, but in the latter half of the 20th century the National Party ruthlessly advanced the frontiers of white territorial ownership by inventing a tangled web of illusory borders for bogus Bantustans. The obdurate Cabinet Minister Connie Mulder made their intention absolutely clear: “As far as the black people are concerned, there will not be one black man with South African citizenship.”

Bantustans may have been figments of demented imaginations, but the aim, once again, was to export the problem – the problem being, in the minds of apartheid ideologues (and millions of white citizens), the presence of black Africans.

In the late 18th century, faced with congested prisons and fearful of social unrest from the “criminal classes”, the British government resolved that their penal crisis should be expelled “beyond the seas”. At first West Africa was considered for a penal settlement, then present-day Lüderitz Bay in Namibia and even what later was to become a fashionable holiday resort, St Francis Bay in the Eastern Cape. At the last moment Botany Bay, significantly further “beyond the seas”, was chosen, leading to the colonisation of Australia.

So while European powers were able to export their social problems “beyond the seas”, the National Party did not have that option. Instead, they disastrously endeavoured to export their “black problem” internally. Frontiers, in other words, can create mental as well as physical borders.

Today, following the dispossession of black dignity and land, we face the fall out. The final frontier is the one, usually colour-coded, which runs right through our heads, and very visibly in the high walls, razor wire and armed response signs all over suburbia.

In the United States, even after the western frontier had reached the Pacific Ocean, the potent metaphor continued to resonate. In 1960 President John F Kennedy proclaimed, “We stand today at the edge of a New Frontier – the frontier of the 1960s, the frontier of unknown opportunities… Beyond that frontier are uncharted areas of science and space.” Ronald Reagan, justifying his anti-communist foreign interventions, called South America, “our southern frontier”.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, George HW Bush hailed the opening up of new markets in Eastern Europe by declaring, “in the frontiers ahead, there are no borders”. On signing the Nafta Treaty, President Bill Clinton proclaimed, “this new global economy is our new frontier”. Later George W Bush called for a war on terror in order to, “extend the frontiers of freedom”.

But Donald Trump’s promise of a “beautiful” border wall, Grandin points out, is no less than “the negation of the frontier”. As a result, Grandin contends, “America finds itself at the end of its myth”, left to confront multiple unresolved domestic problems pushed aside by the pursuit of an ever-expanding frontier. This delay, says Grandin, has now produced: “extremism turned inward, all-consuming and self-devouring”.

But Grandin makes a further telling argument – “the point isn’t actually to build ‘the wall’, but constantly to announce the building of the wall”. It’s the constant threat of invasion or internal subversion that keeps people in line, a tactic fruitfully exploited by the National Party in South Africa and autocrats almost everywhere.

It is the theme of Constantine Cavafy’s marvellous poem, Waiting for the Barbarians (borrowed by JM Coetzee for the title of his famous 1980 novel), where the cowered populace fearfully wait for the arrival of the barbarians, but they don’t materialise, and the poem ends:

“Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

“They were, those people, a kind of solution.”

This is the dilemma facing the incoming administration in the US. Without the fear of invading barbarians, without a need to cower behind a big, “beautiful” wall, the Biden-Harris government will have to deal with the multitude of problems that have stacked up within their own borders, including heightened racial tensions, and where the refusal to wear masks as protection against Covid-19 is treated by many Trumpists as an act of political defiance.

Similarly, our frontiers, physical and psychological, have again come up against the limits of our imaginations. Yesterday’s mental borders continue to seal off so many South Africans into insular and mutually excluding attitudes, shaped by their understanding (or misunderstanding) of our history. No one knows what the Covid pandemic will bequeath, save that the poor, the majority of the population, will be even poorer, and that viewpoints remain primarily defined by race. To change this wretched trajectory we need to re-evaluate our past in order to reimagine a very different path.

A return to normal, even our recent “normal”, will merely reaffirm that it is still yesterday in South Africa. DM

Bryan Rostron has lived and worked as a journalist in South Africa, Italy, New York and London. He has written for The New York Times, the London Sunday Times, The Guardian, The Spectator and was a correspondent for New Statesman. He is the author of Robert McBride: The Struggle Continues and five previous books, including the novels My Shadow and Black Petals. He lives in Cape Town.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Any self-respecting proper criminal will just walk through the front door like the 9/11 terrorists did. Weirdly, Trump’s Mexico fence spun off well for an SA company that put up 30 foot fences along sections of the border. Apparently the coyotes have not heard of battery powered angle grinders to cut through 2mm fences… price-less or actually trump-and-price-less

Still counting votes , Biden is not President elect !