Daily Maverick 168

The man who blew up Koeberg

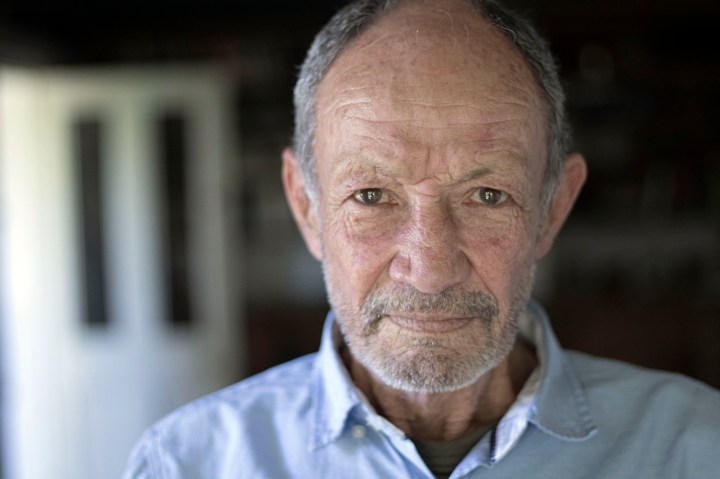

In 1982, Rodney Wilkinson planted four bombs inside the Koeberg nuclear power station in Cape Town and rode to safety on a bicycle. Now 72, Wilkinson has told his story to only a handful of journalists over the years – and there are a few things he wants to get straight.

First published in Daily Maverick 168

Thirty-eight years ago, Rodney Wilkinson committed the only act of nuclear terrorism ever carried out on the African continent. It has been described as one of the only successful attacks on a nuclear base in world history, and is still listed by the ANC’s military wing uMkhonto weSizwe as one of its greatest triumphs in the struggle against apartheid.

Yet on the rare occasions when the story has been told over the past four decades, it has largely been treated as frivolous: as a kind of white-boy caper, or a hippie prank that succeeded against the odds.

One of the first things Wilkinson wants to make clear is how much this interpretation irritates him – because he says that the act of sabotage he executed on 17 December 1982 was meticulously planned.

“Right from the get-go, it was: Avoid civilian casualty, and don’t spill radiation. We don’t want to evacuate Cape Town. Right from the scratch,” Wilkinson said.

We had travelled to Knysna to hear Wilkinson tell his story in the wood-panelled house he is currently sharing with his 98-year-old mother. Upon our arrival, he leapt into the road barefoot to welcome us. His agility was a reminder that in his youth Wilkinson represented South Africa internationally in the sport of fencing. He might have entered the history books only as a Springbok fencer, had he not also blown up Cape Town’s nuclear power plant in 1982.

In preparation for our visit, Wilkinson had laid out neat stacks of documents and photographs. While he spoke, he consulted a small notebook he had filled with handwritten notes in preparation for the interview.

He said it was important that we get things right. Over the years since the bombing, he has told his story to only a handful of journalists, and had often been disappointed with the results. This is, quite evidently, a story that means a great deal to him: one of a few defining narratives of a life which began 72 years ago in northern Johannesburg.

Wilkinson, born in 1949, was the archetypal Boomer baby. His parents were office workers, but what had a greater influence on his childhood was the role his father had played as an artillery major in World War II.

“We’d grown up in the atmosphere of a victorious war against fascism,” he says, openly describing himself as having “romanticised violence and war” from a young age. This predilection, mixed with his outrage at the brutality he witnessed being meted out to black South Africans on a daily basis, was to combine with a reckless anti-authority streak and a taste for danger that would one day lead him to enter Koeberg with four limpet mines concealed in his overalls.

An anecdote he delivers with some relish, which seems to capture the antic spirit of the young Rodney Wilkinson, is the tale of how he ended up leaving the army after three months because of a broken skull. It was 1976, and Wilkinson had been called up again by the apartheid military after failing to appear for duty following extended travels after a Springbok fencing tour.

In Angola, waiting to be transported home to Cape Town, Wilkinson and a dozen other soldiers stole one of the army’s occupation vehicles, loaded it with beer and absconded to what is now Namibia.

“I decided that I would drive the truck: I would drop them all at the Windhoek airport and drive the truck until it ran out of petrol. The trouble was, I fell asleep at about two o’clock in the morning, and crashed the truck over a culvert. And it landed on my head and my skull.”

Astonishingly, Wilkinson escaped punishment. The vehicle he had stolen was in use as part of an illegal occupation, and he says the army had no wish to draw attention to that. Wilkinson was discharged and moved to Cape Town, where he lived on a commune near Paarl and tried to make a living teaching fencing before one of his pupils suggested he might use his skills as a trained draftsman to find employment at the construction of the Koeberg nuclear power station.

The “political and ecological nastiness” of the Koeberg project was not to Wilkinson’s taste – but he decided he would take a job there with the express purpose of figuring out a way to sabotage it.

Wilkinson was not the only one eyeing the Koeberg project with the aim of undermining it. Around the same time, Oxford doctoral candidate Renfrew Christie was amassing as much intel as he could about Koeberg under the guise of his academic research into South Africa’s electricity system. Wilkinson’s and Christie’s paths would never formally cross at this time – but it was Christie who would supply vital information as to how Koeberg might safely be blown up, which a judge inadvertently broadcast to the world when he read aloud Christie’s confession at his treason trial in 1979.

After 18 months working at Koeberg, Wilkinson had not made much progress with a plan towards thwarting the apartheid regime’s nuclear aspirations.

“The best I could think of doing was to steal a set of plans and hand it over to someone who would do something,” Wilkinson says ruefully.

The woman who was to become his wife, Heather Gray, encouraged Wilkinson to do just that, and to take the plans to the ANC leadership in exile in Zimbabwe. There, it was Mac Maharaj – later to become spokesperson to former president Jacob Zuma – who eventually made the suggestion that Wilkinson himself carry out the bombing of Koeberg.

“[Maharaj] told me some people are good at some things,” Wilkinson recalls, “other people are good at other things. You can sing, or you can paint, or you can talk, or you can do this sort of stuff.”

Wilkinson was sold. His first job was to return to Cape Town and get another job at Koeberg, which he had left three years earlier with his stolen plans. In this he succeeded: one of a series of extraordinary strokes of luck, or extraordinary acts of negligence by Koeberg authorities. Even better was the access his job – of making drawings of the piping – gave him to the most sensitive areas of the plant.

Wilkinson and his ANC handlers had determined that they wanted the damage to Koeberg to be substantial and expensive to fix. But most critical was the principle that no civilians should be harmed, so the explosions needed to take place before the work on Koeberg was completed.

“It was obvious from early on that there was no way we could permanently damage [Koeberg],” says Wilkinson.

“It was just too big, and anything we did, they could counter. So it had to be a political statement. And it had to be done safely before the startup.”

The chosen weapons: limpet mines, which Wilkinson needed to be trained to install and detonate. The chosen locations: the nuclear reactor heads, a section of the containment building and a cluster of electric cables under the main control room.

Ahead of the chosen day, Wilkinson and Gray collected four limpet mines from hidden locations in the Karoo. Wilkinson concealed the mines in a secret compartment in his Renault, drove on to the site, and from there carried the mines into the power plant concealed in his overalls. After he’d set the bombs, he left the plant as usual: the bombs were set to explode 24 hours later, when Koeberg would be almost totally empty. By the time they detonated, causing at least R500 million (in 1982 value) of damage and delaying the Koeberg project for 18 months, Wilkinson was gone. He had ridden to safety on a bicycle across the Swazi border after being driven there by his sister. He was never caught, which he believes was the result of a deliberately sloppy investigation, since authorities stood to be further humiliated if the truth came out.

“I was never vetted for the job or the access to the nuclear island,” Wilkinson says. “I had access everywhere, even where I didn’t need it.”

It was only in 1995 that Wilkinson’s identity as the Koeberg bomber was made public, following a leak to the media. Wilkinson was working at the time for the National Intelligence Agency, where he spent the majority of his post-apartheid career.

All these years later, Wilkinson still seems curiously frustrated about the fact that his role in the Koeberg bombing was revealed at all. He says he would rather have remained anonymous to the end.

“It just makes a better story,” he shrugs.

Today, Wilkinson says he has no regrets. Would he do it again? “I will,” he says, with a wolfish grin. It’s a joke. Probably. DM168

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thank you for documenting this astonishing part of South Africa’s struggle, and nuclear energy, histories so clearly!

I wonder what Wilkingson thinks of the present state of the anc?

Maybe he could sort out Zuma and Ace.

Another ANC usefull idiot who was fooled by the ANC master thieves of the peoples money on the basis of skewed self serving ideology…………..

The bicycle bomber!! And here he is at last!!

Give him a bicycle and direct him to Luthuli House.