Daily Maverick 168

2020 Elections: Africa may yet teach the US a lesson

The United States has for decades positioned itself as the paragon of democracy while promoting the system worldwide, but democracy in the US is less perfect than the country would like the outside world to believe. Could the younger democracies in Africa perhaps help shine a spotlight on its flaws?

First published in Daily Maverick 168

Americans will be voting in a few days’ time and political opinions are polarised like never before. Already snaking queues for early voting are resembling those seen in South Africa during the country’s first democratic elections in 1994. By the end of this week, and with a few days to go still before election day, the number of people who have voted in the US already exceeds more than half of the 140 million voters who turned out in the 2016 elections.

Many told journalists they wanted to avoid election day crowds amid the Covid-19 pandemic, but they also cited as a reason a distrust of the voting system related to reports that the country’s postal services could deliberately delay the delivery of votes.

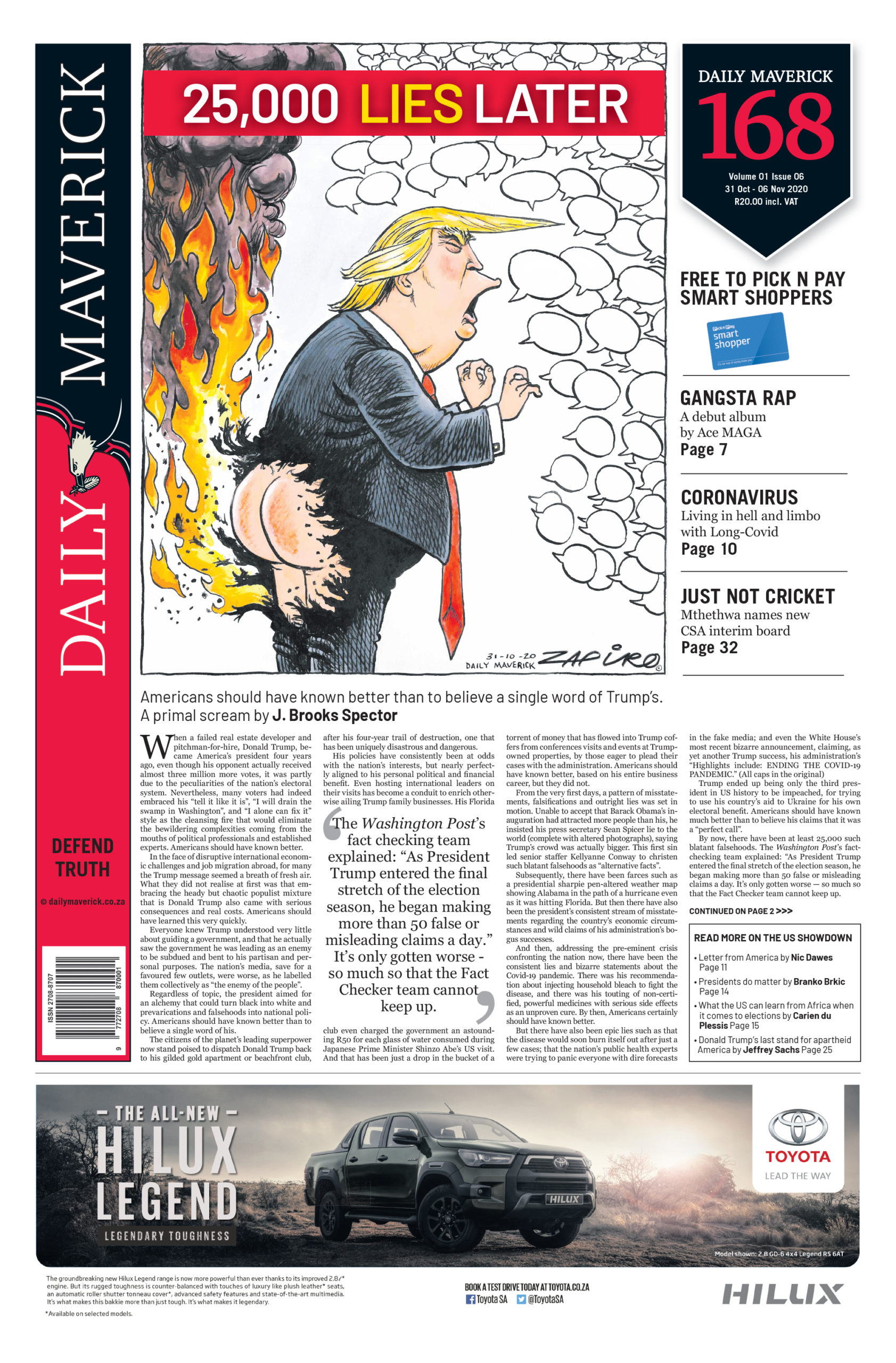

Democracy in the United States, and in particular the voting process, is less perfect than it would like the outside world to believe. Both President Donald Trump and his contender, Joe Biden, during their campaigns expressed distrust in the electoral system. Even though many started raising questions about the way it works after Trump became president in 2016, the problems started earlier.

The Electoral College system – where citizens in effect elect a slate of ‘electors’ who a few weeks later cast the votes for US president – means the presidential election “is really a patchwork quilt”, with various states having their own rules for the elections, says Paul Graham, former director of Freedom House in South Africa.

“The Electoral College was invented for a time when the only way to choose a president was to send your delegate in a carriage to go vote in Washington, DC,” he says. Even though the electors’ votes usually align with the popular vote, it could happen that a candidate with fewer popular votes trumps the other, as happened in 2016 when Hillary Clinton lost with the higher number of popular votes.

Graham says South Africa’s proportional representation system is a lot simpler and allows for more flexibility than a first-past-the-post system, where a small margin of 500 votes can make a big difference.

“There are elections in Africa that are better run than in America,” professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham Nic Cheeseman said. “If you go to Ghana now and talk to the Ghanaians about the fact that you don’t have a central electoral authority [in the US], that you don’t have one set of rules for registering to vote, you don’t have one set of rules for casting your vote, and you don’t have one set of rules for announcing the vote, they’d be appalled and amazed,” he told a webinar on this topic on Monday, hosted by The Resistance Bureau, a US-based discussion group on democracy and freedom in Africa.

America’s democracy, which dates from the 18th century, is much older than the post-colonial democracies in Africa, most of which were put into place towards the latter part of the previous century.

The founding fathers of American democracy “expected the US electorate to always be white men, and everything around the US electoral system since then has been designed and shaped and reshaped to protect the interests of white men”, said Sithembile Mbete, political sciences lecturer at the University of Pretoria.

She said it was designed to appease the losers of the Civil War in the 1860s and reassure them that they weren’t going to lose their rights as white men in the US. This meant that states were given complete autonomy over the management and funding of elections. Rules differ from state to state, over things such as whether photo IDs are used in the voting process or not. There is also no uniform voters’ roll or a national election body that oversees the management of elections at a federal level.

“The US doesn’t have a properly democratic system in the way US organisations design democracy for Africa,” she said. “If any American organisations come to Africa to advise on setting up democracy, you have an independent electoral commission, an audited voters’ roll, you have a set of uniform regulations for everything from the number of observers at a polling station to the opening hours of polling stations to the kind of paper that you print the ballots on.”

She also said the American judicial system was “deeply politicised” in a way that would be considered unacceptable in an ideal African democracy.

Mbete said there were rules and codifications for what were considered to be “good” elections, but “not a single one of these electoral components exist in the United States” – yet US elections are considered to be credible. “America’s a democracy because America says it’s a democracy, so we all believe America is a democracy so no one sends election observers to the US,” she said.

This isn’t strictly true. Even though there are no observers from African countries, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s (OSCE) Parliamentary Assembly has been sending observers for the past 16 years. This year, however, as with some recent elections in Africa, the main obstacles facing observers is the Covid-19 restrictions on travel, which means the organisation will be sending far fewer observers than normal. They will go to nine out of the 50 states. There are even a few states where international observers are banned. The OSCE will keep an eye on issues such as campaign finance transparency, election security, voter ID requirements and ballot access for independents and minor parties.

The Carter Center, which usually observes elections around the world, for the first time this year announced that it would launch a campaign in the US to supply public information about the election, and encourage election officials to maintain transparency and access for observers. It won’t, however, deploy observers.

The race between Biden and Trump is close. Civil society organisations have expressed fear over what a possible second term for Trump could look like, and the word “authoritarian” features strongly in this. “Trump is a blessing to dictators around the world,” said Omoyele Sowore, Nigerian human rights activist and founder of online news agency Sahara Reporters. “He’s creating a global system of gangsters.”

Sowore bemoaned the fact that Trump even had black support in Nigeria because he had convinced far-right Christians that he was fighting on their behalf. “There were churches that [recently] had a rally for Trump while their brothers and sisters were fighting against police brutality,” he said, with reference to the ongoing #EndSARS protests in Nigeria.

These protests are considered to have been inspired by the Black Lives Matter protests in America, when thousands of people in the US and across the world protested against the death of a black man, George Floyd, under the knee of a white police officer in Minneapolis in May. These protests were as much a vote of no confidence in Trump as they were against the policing system in the US, Sowore said.

But Kenyan columnist and commentator Patrick Gathara reckons it would be a grave mistake to think the US’s current problems could be fixed by getting rid of Trump. He said power had been accumulated within the presidency over a long time, as had the lack of accountability in the system. American civil society groups had not been pushing back firmly enough, and it would be a long-term fight. “It won’t be fixed by one election.”

There were some lessons from Kenya, where voters were frequently told that “all we need to do is to vote the good guys into power”, he said. “In Kenya, we put in dictator after dictator, and always the next guy is supposed to be the good one, but it never really works out that way.” In 2002, when Mwai Kibaki became president, the whole Kenyan government was replaced by “the opposition and civil society people [were] people with integrity”, he said. “They suffered for the stance they had taken on behalf of the people, and yet overnight they changed because the incentives that were built into the system that we put them in simply meant that they were going to turn.”

He said there had to be a rethink about the systems democracies want. “Behaviour is modelled by systems. It is influenced, it’s incentivised, by the system.”

Cheeseman has warned that “some kind of violent political incident is more likely than not” around the elections. This is because American institutions have been weakened and lack trust; there’s a high rate of gun ownership in American society; leaders are irresponsible and populist and have indicated that they might not accept the result of the elections; and it’s a closely contested election with the possibility of a last-minute upset should the postal votes reverse a Trump on-day victory at the ballot box. A similar last-minute switch in the 2007/8 Kenyan elections contributed to the violence there. “I’m really worried about where the US is right now,” he said.

This could be unchartered territory. “The international system is not built for a collapse in the US,” Mbete said. “The post-World War 2 world order is based on the US being stable, being democratic, and being rich. Our multilateral institutions don’t know how to handle a US with post-election violence.”

On the upside, this moment could provide an opportunity for democracies to self-reflect, and pay heed to the successes in African elections. Cheeseman said in future there should be less emphasis on the promotion of US democracy abroad, and more of an emphasis on a global conversation about renewing democracy. Issues such as racism or challenges with elections systems “should be put on the table so that it’s a genuine conversation and partnership about how to arrive at democracy everywhere”. DM168

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

It may be true that Americans could learn from Africa, that’s debatable, seeing as even “democratic” governments have been hijacked continent-wide by tinpot dictators masquerading as “struggle heroes”. However, only the 1994, and maybe the 1999 South African elections are worth examining. Since then, the parade of greedy, deceitful, corrupt, and destructive leaders (and I include all levels of government and their failed State-Owned Enterprises) has been never ending – cadre deployee after comrade member has engineered the destruction of a once shining rainbow in Africa, which has been reduced to a pile of smoking ashes, and its economy with it. Even Trump at his worst would be preferable to this.