Humans of Covid-19

North West mortician: ‘People are terrified when they have to come and identify the bodies’

Maverick Citizen will this week share the stories of 26 workers who have been at the frontline of the Covid-19 response. These men and women work in health facilities in the nine provinces, some as doctors, others as nurses and some as mortuary workers, cleaners and porters. Journalist Nomatter Ndebele and photographer Thom Pierce undertook the challenging task of crisscrossing the country, at times under tight lockdown regulations, to document the stories of these incredible people who do not view themselves as heroes. In the second episode they go from Limpopo to North West to Mpumalanga.

Read Episode 1 here.

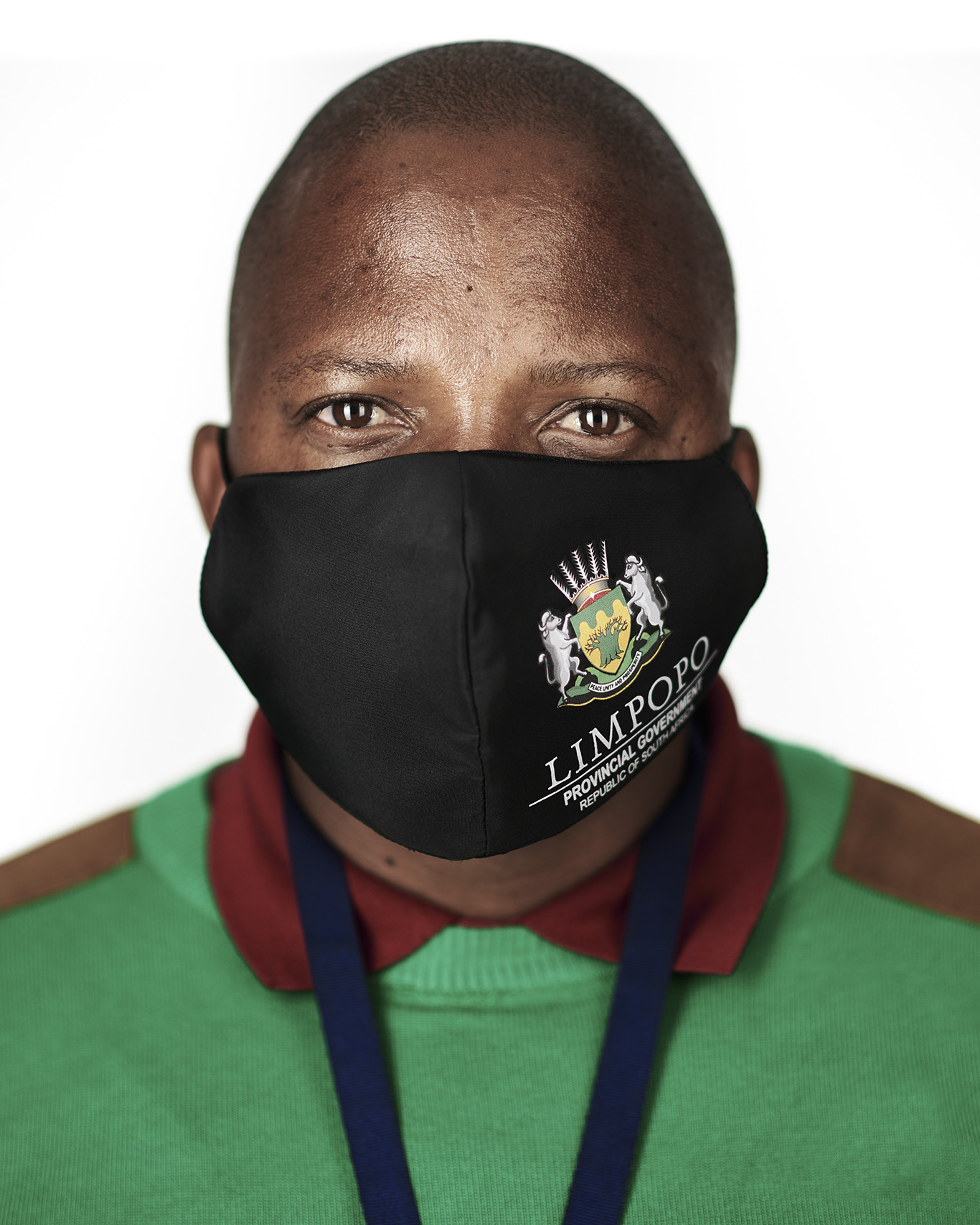

Lesley Mabena, Polokwane, Limpopo. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

Lesley Mabena: Cleaner, Limpopo

When the government introduced level 5 lockdown, most were lucky enough to be able to stay home and stay safe. It was understood that all essential workers were to continue their services. In the context of the healthcare system most immediately thought of doctors, nurses and paramedics, but did not always consider the support staff who work in health facilities. Not many people thought about the likes of Lesley Mabena, who works as a cleaner at Polokwane (Pietersburg) Provincial Hospital in Polokwane, Limpopo.

Mabena and his colleagues were also required to be at work. They were as exposed and vulnerable as medical staff. “It was such a difficult time. We were so afraid and we knew nothing. We thought that we could even get infected just by touching the water at the hospital,” he recalls. The early days, when little was still known, were the hardest.

Hundreds of hospital workers were gripped by fear. The last thing they wanted was to be in a hospital facility. “In the beginning we didn’t turn up for work, we were so afraid that we couldn’t even bring ourselves to step into the hospital,” he said.

The situation was untenable. Hundreds of fearful workers had turned to unions in a desperate attempt to protect themselves and their families from this unknown virus. Dr Phetho Mangena took it upon himself to engage the cleaners at the hospital and educate them about the virus.

Lesley Mabena, Polokwane, Limpopo. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

With more information, Mabena and his colleagues started to understand that although they were fearful, they could protect themselves from the virus. “Dr Mangena really took the time to speak to us, to educate us. Everything we know we learnt from him. But he also expects us to be responsible, and he put that responsibility in our hands. I remember the one day I went into work and forgot to change into my boots. I went into the hospital in my normal shoes. I bumped into Dr Mangena and he gave me a hell of a talking-to. He said, ‘If you don’t want to think about yourself, then think about your children.’ That made me realise that I had to take responsibility for myself,” said Mabena.

When the hospital faced challenges with staffing, he was part of a group that was requested to take on a full-time cleaning role in designated Covid-19 wards. “I felt like a hero. When people refused to come into work, we were sent in.”

Over time, the hospital started organising educational workshops for support staff. The workshops went a long way in combating misinformation, and giving people the confidence to know that they could still do their work and be protected. The hospital went to great lengths to ensure that Mabena and his colleagues had all the personal protective equipment (PPE) they required.

“I have to tell you, we have never once been without PPE, not a single day,” he said.

Reflecting on the past couple of months and the challenges he faced at the start of the pandemic, Mabena reckons that the biggest problem alongside raging fear was a lack of information.

“The real problem was that we were all just hearing rumours and then spreading those misinformed rumours [among] each other. Once we were given more knowledge, that started to die out,” he said.

During a recent workshop at the hospital he was asked to share a bit about his experiences while working in the pandemic. “I got up and said one or two words and after that, people were volunteering to come and work in the Covid-19 ward,” he said proudly.

One of the biggest lessons he has taken from being on the frontlines of the pandemic is the importance of playing your part. “There is a lady who worked at the hospital, and she refused to come to work. She was later diagnosed with Covid-19 and it was her colleagues who had to treat her. That just made me realise that we should guard against making decisions that could work against us in the future,” said Mabena.

Vader Molefe, Klerksdorp, North West. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

Vader Molefe: Mortician, North West

It is 8pm when I finally get hold of Vader Molefe. He works as a mortician at Mamokomane Funeral Parlour in Klerksdorp. “I’ve just finished work. We’ve been waiting on a delivery of caskets,” he said.

By now Vader and his colleagues are accustomed to long hours and sleepless nights. Their workload as morticians has almost tripled as the country battles through the pandemic. Mamokomane Funeral Parlour has been helping Klerksdorp-Tshepong Hospital in storing the bodies of deceased patients during this time.

Even for someone like Molefe, who is accustomed to death, working on the frontline has been overwhelming. “Even before our numbers started picking up in North West we were picking up five to six bodies every day. When things really got serious we were called in to work at 10am and were up all night,” recalled Molefe.

What used to be an “ordinary” pick-up for the funeral parlour has become a much more rigorous exercise. “When we get the bodies, they are wrapped in three bags. We then add another one. We transport the body in a panel van, and when we arrive at the parlour we put the (coronavirus)-positive bodies in a specific fridge. After that we remove our PPE, have a shower and go out to sanitise the vehicles,” said Molefe.

Vader Molefe, Klerksdorp, North West. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

Regardless of how many bodies come in, the process is exactly the same. “If there are six bodies in a day, then we shower six times,” said Molefe.

One of the greatest challenges that Molefe and his colleagues have faced in this time is coming across as the gatekeepers of grieving. Regulations now stipulate that only two family members are allowed to view bodies in order to identify them. Molefe and his colleagues often have to be the bearer of bad news when five members of one family turn up at the parlour. “It’s hard. We say to them, ‘We know there are five of you here, but we can [only] allow two of you to identify the body.’

“The two people who are elected to identify the body are then put into full PPE for the viewing,” he said.

Grief is a difficult thing and in times like this, it is made even harder when people are unable to rely on familiar funeral rites. There is also still a lot of stigma associated with Covid-19. “A lot of the families refuse to believe or accept that their family members have died from Covid-19. And most people are terrified when they have to come and identify the bodies.”

Like most frontline workers, Molefe said it had been an incredibly difficult time. “But you know what, this thing is here and it is real, but it will pass. For now, ijob yijob.” (A job is a job)

Mica Engelbrecht, Bethal, Mpumalanga. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

Mica Engelbrecht: Pharmacist, Mpumalanga

“With both of us being ‘essential’ healthcare workers, my husband and I have had to be on duty since the start of level 5 lockdown. We have two beautiful boys, so with schools closing down we had to send them to stay with close family for more than two consecutive months. We missed them dearly and will always remember the sacrifice we had to make during this year. I thank God for their safety.”

When the pandemic took off Mica Engelbrecht and her partner were forced to make difficult decisions about protecting their family, but also the hundreds of ordinary South Africans who needed their assistance.

Sello Molomgoana, Mokopane, Limpopo. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

Sello Molongoana: Admin clerk, Limpopo

“It has been hard dealing with the anxiety and fatigue from the challenging situation at the hospital, but it has allowed me to put more focus on my wellbeing and to deal more effectively with stressful environments.”

Sello Molongoana is an admin clerk at Mokopane Hospital in Mokopane, Limpopo. The pandemic saw his and his colleagues’ workload triple. He believes that the situation forced him to take his mental and physical wellbeing more seriously.

Nomshado Manana, Kwamhlanga, Mpumalanga. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

Nomshado Manana: Porter, Mpumalanga

For 15 years Nomshado Manana has been accustomed to attending to patients when they arrive at KwaMhlanga Community Hospital. The process of assisting patients out of their mode of transport and into the hospital facility was always strenuous. But now, with the onset of the pandemic, the process is further riddled with fear and uncertainty.

“Things have really changed. Sometimes I don’t enjoy being at work anymore because I am so stressed about getting sick myself or infecting my family,” said Manana.

The interactions between porters and patients have really become strained during this time as both parties have started to view each other with suspicion.

“You know people can come in with a fever and it could be completely unrelated to Covid-19, but, lately, the minute someone is screened and they have a high temperature, we immediately think Covid,” she said.

Nomshado Manana, Kwamhlanga, Mpumalanga. (Photo: Thom Pierce)

The need to screen patients upon arrival has also added an extra aspect to Manana’s work. “I can’t just go straight to a patient and help them anymore, I need to find someone to screen them first, and if they present a high fever you can immediately see them become anxious and they can see our anxiety too. And that doesn’t feel good for patients.”

As more information became available, Manana’s fears and worries eased. Learning about co-morbidities was a big turning point.

“When we learnt that if you did not have co-morbidities, you had a high chance of surviving the virus, things felt much better,” she said.

Although Manana still worries about possible infection, she says that she and her colleagues have become used to working with “persons under investigation”. And as the number of positive cases decreases, workers feel less overwhelmed.

“It’s almost like we’re immune to it now, not necessarily physically but mentally. We are used to it now and we have much more information, so things are a lot more bearable.” DM/MC

Read Episode 1 here.

Nomatter Ndebele is a writer who specialises in human interest stories. She is passionate about people and telling their stories in a way that inspires human connection. When she isn’t writing she does work in access to human rights and youth development. Nomatter has been a finalist in the Discovery Health Journalism Awards. Thom Pierce is a British photographer, currently based in Johannesburg, South Africa. His work explores the line between documentary, art and portrait photography to engage with humanitarian issues; through photographic essays, installations and exhibitions. He is passionate about human rights and using photography as a tool to connect an audience to issues of injustice. Over a period of years, his work has developed to become primarily focused on the art of activism through photography. He has won several awards for his work and has previously been chosen as a finalist in the Magnum Photography Awards and selected for the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider