MOUNTAIN OPERA

#BringBackKataza: How the Cape went ape over a single baboon

Over the past few weeks, the vexed issue of baboon management in Cape Town has flared up again – centred on the treatment of a primate called Kataza. The conflict has seen animal rights activists pitted against scientists in an extraordinarily vicious debate.

To supporters, he is known as Kataza. To the rangers who named him, he is Nkatazo. In official documents, he appears as SK11.

His rap sheet is extensive.

April 2020: SK11 raided five occupied houses in Kommetjie.

May 2020: SK11 broke through security 10 times, and attempted to do so another nine times.

“When he broke the line, he generally solicited other individuals to join him in raiding town,” his report reads.

June 2020: SK11 led a splinter troop into the urban area on eight occasions.

July and August 2020: SK11 led the troop into Kommetjie 15 times.

Nkatazo means “trouble” in isiXhosa – and this young chacma baboon has been living up to his name.

Portrait of the baboon as a young male

“How do you recognise Kataza? He has a scratch mark on his right cheek. You’ll usually see him next to Castro, an old female. And now, of course, they’ve put two great big ear tags on him.”

A #bringkatazaback sign hangs in Kommetjie to highlight and promote the safe return of Kataza the male baboon to his troop in the town. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

Jenni Trethowan, the founder of an activist group called Baboon Matters, speaks of the 42 members of the Slangkop Troop as if they are her close friends. She describes baboons as her “soul food”.

It is largely thanks to the efforts of Trethowan and her supporters that Kataza has been painted as a loveable rogue; a daring baboon revolutionary, constantly outwitting the City of Cape Town-appointed rangers employed to keep him out of urban areas. A guerilla, if you will.

To the scientists responsible for devising Cape Town’s baboon management policies, Kataza is a headache – and his human admirers even more so.

Kataza alone in Silvermine Reserve after being relocated by HWS to Tokai. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

University of Cape Town ecologist Professor Justin O’Riain says that research undertaken by his unit in April 2020 recorded Kataza as a young adult male who was submissive to the alpha male of his troop. He had not yet begun the male baboon behaviour quaintly known as “consorting”: prolonged periods of following and mating with receptive females.

“Kataza has since commenced consorting,” O’Riain says.

“But rather than challenge and defeat the alpha male, he is doubling down on pleasures and taking a small group of females to town where food is abundant, and he is having both his cake and copulations.”

Traffic is stopped on Ou Kaapse Weg in the deep south of Cape Town while activists keep watch of Kataza’s movements from a distance and prepare safe passage should he trek back to Kommetjie from Tokai. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

Kataza’s fondness for entering villages like Kommetjie and foraging for food there is not just contrary to Cape Town’s policy of keeping baboons out of urban areas. It presents a further challenge because it seems that the baboon’s intention is to form his own splinter troop.

“He has his own little splinter group of females, he’s trained them, and they also want to go to town with him,” says Dr Phil Richardson, the project manager of Human Wildlife Solutions (HWS), which holds the City’s contract for baboon management.

“Splinter troops are not natural in the wild. But in an urban edge environment like here, you find a low-ranking male not getting anywhere with mating because he gets beaten up by other males. If he can form a splinter troop, he goes from being nothing to being alpha. And the low-ranking females, who always get the food last, also like it.”

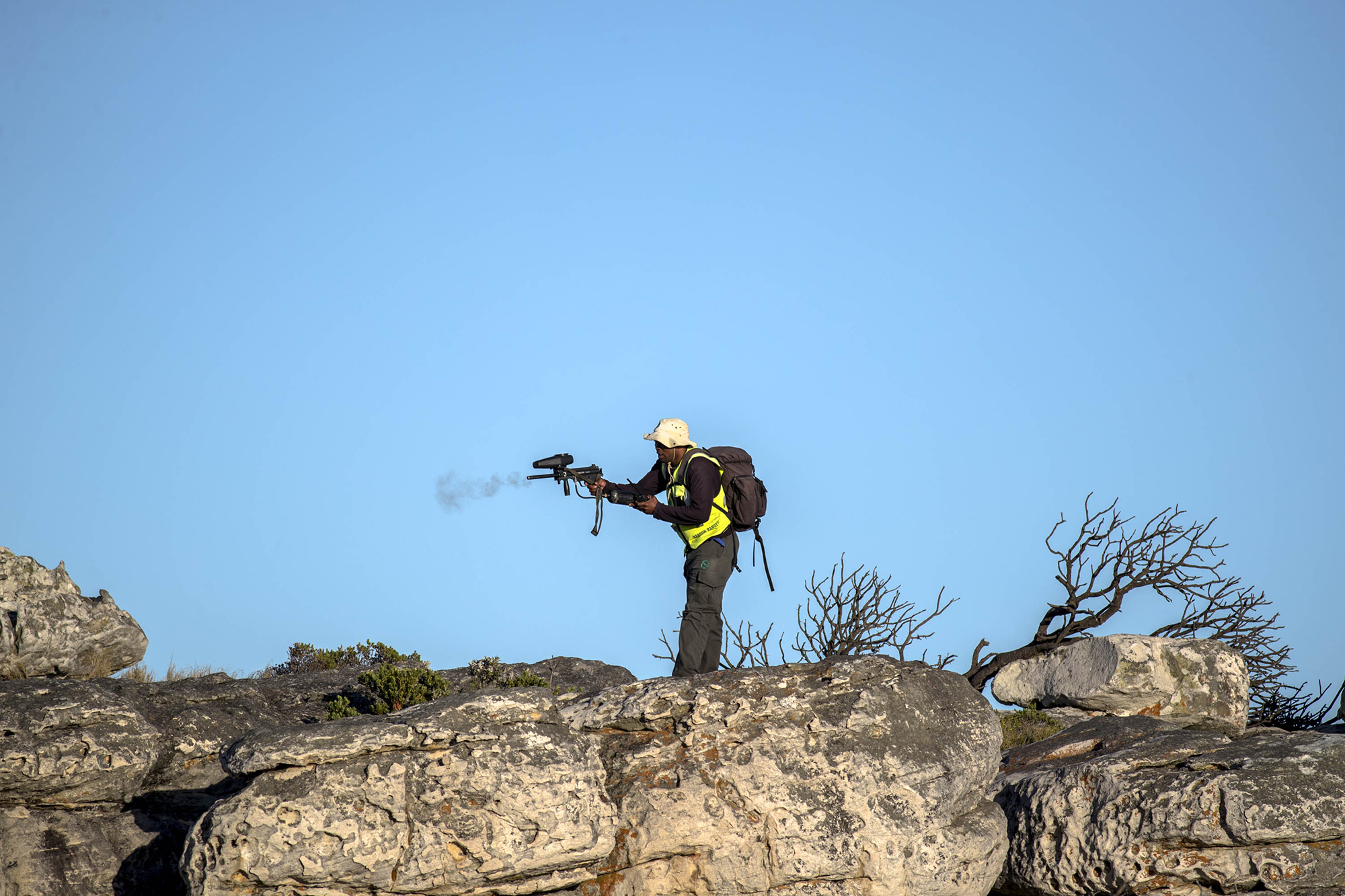

An HWS baboon ranger fires his paintball gun to keep the Slangkop troop contained on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

Splinter troops are anathema to Cape Town’s baboon management policy because they drastically raise management costs. Monitoring two troops of 20 baboons each costs twice as much as monitoring one troop of 40.

Kataza had become a big problem. In the eyes of authorities, something had to be done.

But nothing gets past Jenni Trethowan’s eagle-eyed scrutiny of the Slangkop Troop. So when Trethowan realised Kataza had been missing for two consecutive days, she raised the alarm.

Going bananas over baboons

It is almost impossible to overstate how divisive the issue of baboon management has become in recent years in Cape Town’s Deep South: the colloquial term for the southern part of the Cape Peninsula, encompassing villages like Kommetjie, Scarborough, Noordhoek and Simon’s Town.

A juvenile baboon grooms another on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie after being injured by a dog. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

Though the topic may seem unbelievably parochial to those further afield, it is a regular pressure point in the City’s relationship with residents, flaring into tension every few years.

Those invested in the issue hold passionate beliefs and appear rarely swayed from them. All the major players mentioned in this article are regular recipients of vitriolic emails, slanderous comments on social media and even death threats. Some journalists refuse to report on the issue because the blowback is so intense.

Over the past few weeks, as the Kataza issue has blown up, social media and local talk radio have been aflame.

The Slangkop baboon troop with Kataza forage and groom on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

“Every time anyone on the radio spoke about it, there was immediate and heated response,” Cape Talk drivetime host John Maytham told Daily Maverick.

At least three main camps exist.

The first is led by Trethowan and other baboon activists, who maintain that the City’s approach to baboon management, as implemented by HWS, is both cruel and unhelpful.

They believe that authorities are too quick to euthanise baboons and separate troop members, but a particular sticking point is the use of pain aversion methods to keep baboons away from urban areas. HWS uses paintball guns to dissuade baboons from breaking through the urban edge.

A mother baboon picks up her baby and kisses it in a seldom seen display of affection and love. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

“I have been opposed to the paintballing for years,” Trethowan says, comparing it to corporal punishment.

“Most people these days are not using pain aversion to train animals. These baboons are getting paintballed from the moment they wake up. What is the point of it? You’re not teaching the baboons anything.”

Trethowan and fellow activists recently received high-profile support from the grand dame of primatology herself, Jane Goodall, who criticised the use of “unnecessarily hostile tactics” in baboon management in the Western Cape.

Slangkop baboons warm themselves in the morning sun on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie in the deep south of Cape Town with the Cape Point Nature Reserve in the background. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

In the second camp sit the City of Cape Town’s biodiversity management unit, HWS, scientists like Justin O’Riain, and other prominent international primate experts like the University of California’s Dr Shirley Strum.

After Strum visited Cape Town in 2014, she described herself as “scandalised” by the behaviour of local baboon activists and wrote:

“The epitaph of these baboons will read: ‘Met an untimely end because activists could not face reality’.”

A Human Wildlife Services (HWS) ranger fires his paintball gun at members of the Slangkop baboon troop to keep them contained on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie in the deep south of Cape Town. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

O’Riain points out that independent studies have repeatedly shown that Cape Town’s baboon management project has resulted in “a growing population with improved welfare and communities with far less damage”.

He says that since HWS took over baboon management, the percentage of baboon deaths linked to humans has dropped from 52% in 2008 to 14%. What proved most effective at keeping baboons out of urban areas and therefore safe: paintball guns.

“This is why the NSPCA [National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals] supported the use of new tools which include paintball markers,” O’Riain says.

Two juvenile baboons play on a rock on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

He asks: “How can it be that the only city on the continent that strives through the hiring of professional service providers to keep baboons safe from urban areas is held up as a heartless pariah, and the best performing service provider to date is labelled as inept and cruel?”

In the third camp of the baboon wars are the residents affected by pillaging baboons. In recent years, there have been some horror stories, including a Scarborough baboon called William who reportedly terrorised a pregnant woman living alone with a toddler to the point of ripping off the sliding doors to her home.

William was euthanised in 2010 as a result of his destructive raiding behaviour. On the Baboon Matters website, Trethowan refers to him as “William the Conqueror”, describing him as a “huge, gorgeous boy” and “one of my all-time favourite males”.

Two baboons groom each other on Slangkop Mountain. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

Kommetjie residents recently complained to News24 of baboon damage including the R500,000 destruction of a greenhouse roof. But they appeared almost equally irate about the behaviour of HWS rangers, who were accused of both failing to keep baboons out of town and of causing damage of their own through cowboy-like paintball tactics.

HWS’ Richardson denies that his rangers are trigger-happy.

“Apart from anything else, it would cost us a fortune [in paintball markers],” he observes wryly.

“The rangers are happiest when baboons are far from town, and they can sit there and hold the line. There’s no pleasure in chasing the baboons. The guys really enjoy the baboons. Sitting and watching them forage and play: that’s the ideal situation.”

Kataza and some of the Slangkop troop warm themselves in the sun on Slangkop Mountain above Kommetjie. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

HWS’ website states: “We pride ourselves on being the only company in the world who have found an effective management strategy to prevent human-baboon conflict”.

When it comes to human-human conflict over baboons, however, it’s a different story.

#BringBackKataza

If you drive through Kommetjie today, you’ll see a hand-painted sign hanging at the entrance to the village.

“#BringBackKataza,” it says: the recent rallying cry of Trethowan and her supporters.

The Kataza saga began on Wednesday 26 August: when, in the dry prose of the City of Cape Town’s Julia Wood, “the male baboon was relocated to the Zwaanswyk-Tokai troop in Tokai”.

A Human Wildlife Services patrol staff member on Slangkop Mountain with a paintball gun. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

This was done because Kataza was “compromising the welfare of the [Slangkop] troop” by leading raids into town.

“It was decided to relocate [Kataza] and see whether the troop was more manageable without him. Thus far, it has proven to be – the troop has entered Kommetjie less since [Kataza] was held and then relocated,” says Wood.

In the language of the baboon activists, this intervention takes on different shades entirely: “kidnapping”, with Kataza painted as ripped away from his home and family and cruelly consigned to an alien area. One caller to talk radio compared the incident to the forced removals which occurred during the apartheid era.

When Trethowan realised Kataza’s absence – which had not been publicised in advance precisely to prevent activist and media interference – she started searching for him immediately. Trethowan spotted the baboon crossing Ou Kaapse Weg, the mountain pass which connects Cape Town’s southern suburbs with the Deep South.

“It was clear to me he wanted to go back [to Kommetjie],” says Trethowan.

As recorded in a now widely viewed video, Trethowan proceeded to attempt to “walk Kataza home”.

The small coastal suburb of Kommetjie as seen from above on Slangkop Mountain in the deep south of Cape Town. (Photo: Alan van Gysen)

It was not successful.

“He did start following me,” she says, but eventually the baboon ran back in the direction to which he had been relocated.

O’Riain says Kataza’s relocation was perfectly justifiable: he was released near a troop with a single older alpha male, which should give him a chance “to meet and hopefully mate with unrelated females”.

He points out: “Leaving home and your family is the norm for male baboons. Males spend days alone as they plot and scheme their way to joining a new troop and climbing the ladder to alpha position.”

As things stand, Kataza is living an itinerant life in Tokai, while the debate over his circumstances rages on. One of the places he has been sleeping of late is atop the roof of Pollsmoor Prison.

“Every morning he goes to Tokai and sits there and looks at females. Then he gets chased off. That’s life for a baboon,” says Richardson.

“There’s no truth to the idea that he’s yearning for his old troop. He’s the age where he wants to breed. Every young male who grows up goes through this stage.”

The scientists accuse the activists of rampant anthropomorphism; the activists accuse the scientists of heartlessness.

Trethowan has further been accused of using the Kataza episode as a publicity tactic for fundraising for her organisation: a charge she laughs off.

“I can’t even begin to tell you how offensive that is,” she says.

“I didn’t move Kataza there, they moved Kataza! I have put out one fundraising request in response to people who asked.”

Though they may be at loggerheads, the scientists and the activists have one thing in common: a deep fascination with the species known in Latin as Papio ursinus.

“Baboons have been my life for 30 years,” says Trethowan.

“They are like a soap opera every day. They are incredibly intelligent, caring, and empathetic.”

O’Riain has a tellingly different description.

“They are absolutely remarkable creatures, though their despotism can be very hard to watch: in particular, lots of very harsh discipline on infants. They have agility, power and sociability. And all that makes them one of the hardest animals in the world to live next to.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.