The reason is that future inflation is heavily influenced by human traits such as expectations, perceptions and confidence levels. These are all subject to changing mental models, new narratives and emotions. Much like the future direction of the equity market, no one can predict exactly what will happen next.

But, despite the inflation bears being wrong for a very long time, what is becoming clearer is that the risks of higher inflation over the medium to longer term are building. And if you are not correctly positioned for the possibility of higher inflation as an investor, you need to take note.

Why have the inflation bears been wrong for so long?

The American economist and Noble prize winner Milton Friedman famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” According to his monetarist theory, when the quantity of money increases faster than the rate of economic growth, consumer prices will rise.

In practice, however, it hasn’t always worked out that way.

One recent example of a large monetary expansion that didn’t result in any meaningful inflation was the period following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008. Many expected all the new money being created as a result of quantitative easing (QE) to spur inflation. While QE may have created asset price inflation, it did not create inflation at the consumer level. The likely reason why inflation remained low over the past decade is that the velocity of money – the rate at which money is exchanged through economic activity – did not increase meaningfully. The GFC was first and foremost a financial crisis, caused by concerns about the health of bank balance sheets. Post the crisis, the focus was on repairing balance sheets, which included a reluctance by banks to lend.

So why are we more concerned about inflationary risks today?

There has been a relentless increase in global government debt as a result of the response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The IMF expects the ratio of global government debt to GDP to increase by 19 percentage points this year. Historically, debt growth has never been this quick outside of wartime. And future crises linked to big-ticket societal problems, such as climate change or inequality, may very well be declared emergencies that require similar ‘whatever it takes’ responses, serving as justification for a further big expansion in debt.

In addition, many of the structural drivers that underpinned decades of benign inflation have peaked or are starting to move in the opposite direction. Interest rates have declined dramatically and in many parts of the world have hit the zero bound. Two decades ago, most bonds offered yields above 5%. Today, nearly 90% of bonds yield less than 2%. Politicians are also starting to exert more control over monetary policy, threatening central bank independence, and globalisation (the major engine of low prices and rapid growth over the past three decades) is in reverse gear as populism, nationalism and protectionism are on the rise.

All this new debt will have to be repaid eventually

There are a number of ways in which repayment can happen (about which you can read more here). When debt can’t be repaid through growth alone and default is unpalatable, higher inflation provides a route out of the quandary. Couple higher prices with financial repression, where governments adopt policies that result in savers earning a rate of return below inflation, and debt can gently be inflated away over time.

What does the prospect of inflation mean for investors?

We recently looked at three very different scenarios to show the impact of inflation on long–term investors: the period of hyperinflation in Germany (1921-1923), high inflation coupled with rapid economic growth in the UK post World War II (1947-1970) and high inflation coupled with low economic growth in the US (1968-1982). While these scenarios are not necessarily representative of what will translate in future, they provide useful perspective on a range of outcomes that have historically prevailed.

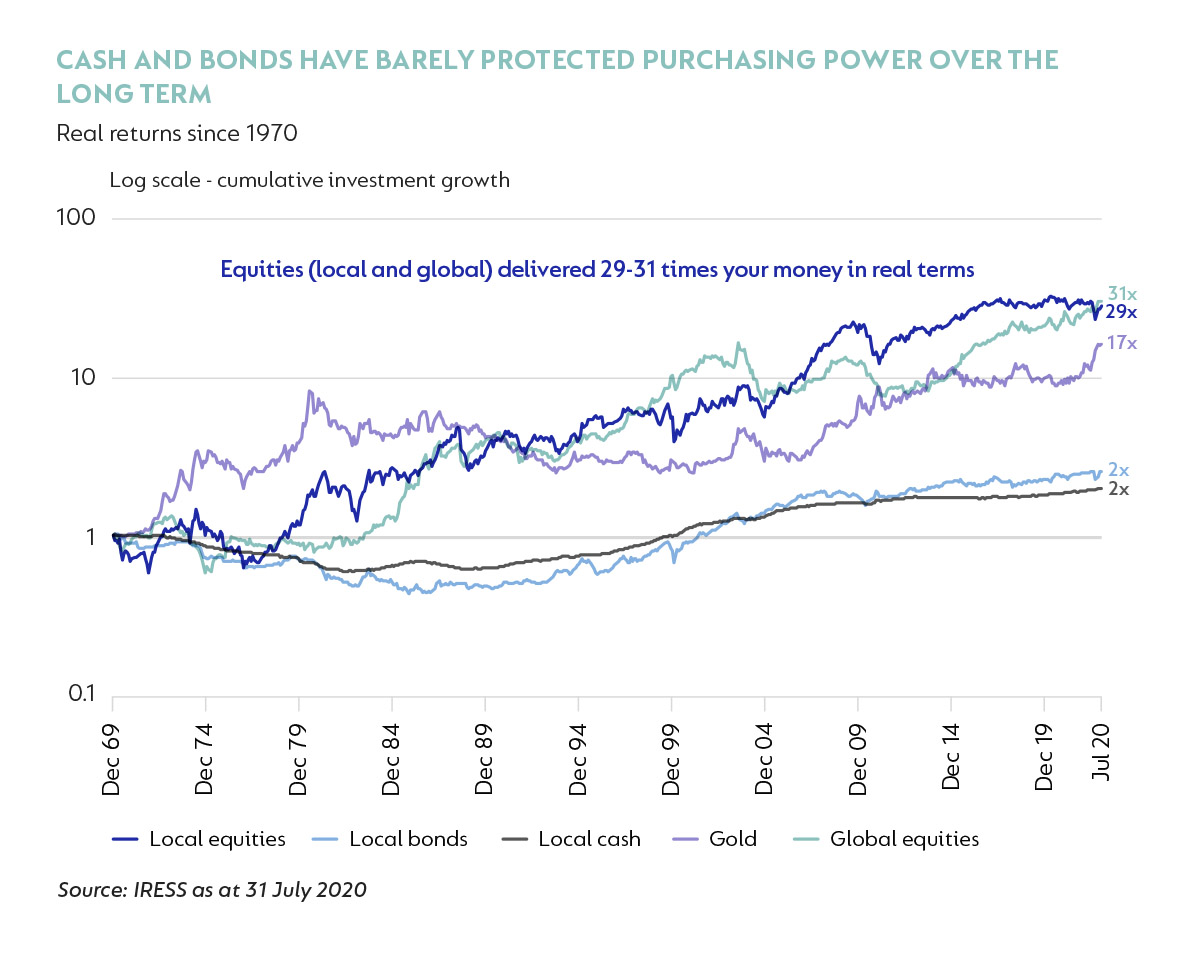

The key insight from all of the inflationary scenarios is that while economic conditions have an impact on the quantum of the returns realised by investors, equities outperform bonds in all periods of rising inflation.

But too many investors are incorrectly positioned for an uptick in inflation

Unless you have been primarily invested offshore or in cash over the last five years, returns have been disappointing. Over this period, most multi-asset portfolios are about 4% to 5% p.a. short of investors’ expectations.

As a result, many investors —retirees in particular— have de-risked by moving out of diversified multi-asset portfolios, resulting in very significant overweight positions in cash or income funds. By our calculations, between R200 and R300 billion worth of capital is currently too conservatively invested in South Africa.

The potential problem for these investors over the medium to long term is that if you are not invested in real assets and inflation starts to tick up, the effect on your savings will be dramatic over time. Cash yields are much lower than they used to be (close to half of the level at the start of 2020) and will remain so for some time to come. For example, our expectations for income fund returns over the next 5 years have declined by roughly 3% compared to prior annual returns of between 7 and 9%.

How do you make your money work harder?

For the foreseeable future, the perceived safety of cash or near-cash investments may become a trap for investors, especially in the event of a possible resurgence in inflation over the medium to longer term.

In a tough economic environment, where financial repression (through lower interest rates over the longer term) may become a necessity, we question the ability of cash to provide appropriate inflation protection, especially when considered relative to alternatives such as more diversified multi-asset portfolios.

To protect yourself against the risk of inflation, we believe it is more sensible to include real assets (such as selected global and domestic equities, infrastructure and property, or inflation-hedged asset classes such as inflation-linked bonds and precious metals) as part of your portfolio. The appropriate exposure level depends on your ability to take risk.

Those who have de-risked their portfolios over the last five years, or who may have invested too conservatively to begin with, need to consider taking action to increase the risk in their portfolio to an appropriate level.

For 27 years, we’ve actively managed funds that can weather the times, whatever they might be. Over the long term, a well-diversified multi-asset portfolio with a wide mandate and adequate exposure to growth assets remains one of the most robust approaches to protecting your purchasing power. If you’d like to learn more about our approach to building resilient portfolios, visit coronation.com DM

The information contained in this article is not based on the individual financial needs of any specific investor. To find out more, speak to your financial adviser.

Coronation is an authorised financial services provider.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Amid this observation that inflation predictions are mostly faulty, the FSCA plans to legislate the communication of projected pension values to fund members!