BOOK EXTRACT

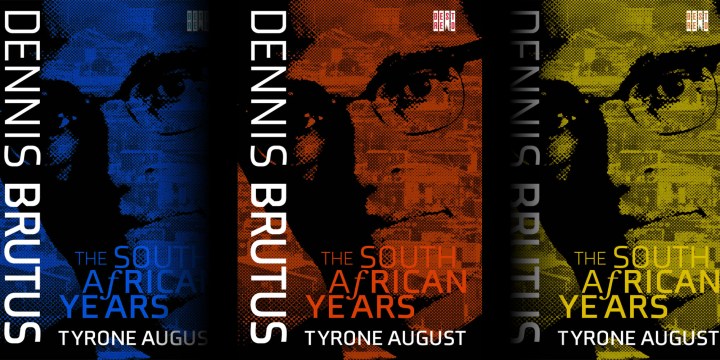

Dennis Brutus: The South African Years

Despite his storied life as an anti-apartheid activist, journalist, poet, teacher and sports administrator, little has been written before about Dennis Brutus, who was variously detained, sentenced to jail, banned and then forced into exile by the apartheid regime. Veteran journalist turned academic, Tyrone August, edited this extract from the introduction to his new book on Brutus, which is published by the HSRC Press.

Tracing the contours of another person’s life is a fanciful ambition. Not only does it involve constructing a chronology of certain events, it also encompasses an enquiry into that person’s interior world. The notion that it is possible to fully accomplish both tasks is, in some ways, rather preposterous. An adult life usually extends over several decades; this time span includes an infinite number and variety of experiences. How, then, does the would-be biographer identify the formative moments in the life of an individual? And, in the absence of any divine power, how does the invariably self-appointed scribe gain access to the innermost thoughts and emotions of that individual?

Without the direct involvement of the subject of enquiry, whether as a result of death or circumstance, a biography becomes an even more daunting enterprise. This absence deprives the biographer of the single most important source of information. And, if some participants or witnesses in that person’s life are unable or unwilling to share their memories or knowledge, this leaves even bigger gaps. Such information, over which only they preside, remains lost forever – unknowable and irretrievable. The biographer then, perforce, comes to rely extensively on information in archives – a distinctly unsatisfactory dialogue with the past.

Why, then, embark on a project that may be encumbered by such profound difficulties? More often than not, the intention is to acknowledge, and even honour, a life well lived, marked by some distinction (with, of course, many dishonourable exceptions for perhaps equally justifiable reasons). In this instance, the subject of attention is Dennis Brutus, who lived in Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape during the first half of the 20th Century – a tumultuous period that saw the emergence of apartheid, a legally codified system of racial segregation and discrimination, followed by the development of a ruthless state apparatus designed to systematically eliminate any resistance. It was within these grim circumstances that Brutus, who was classified as coloured under the Population Registration Act of 1950, distinguished himself as a student, teacher, poet, journalist, sports administrator and anti-apartheid activist.

Yet, despite this range of achievements, there is not a single biography on Brutus, nor did he publish any extended autobiographical work in a single volume …

*****

But, in the long run, renewed interest from potential biographers was probably inevitable. Brutus’s life is woven far too deeply into the fabric of the recent history of South Africa. This is true especially of the first four decades of his life which, as the most important period in his personal, literary and political development, is the particular focus of this biography. His childhood in the mid-1920s and 1930s is also the story of Dowerville, one of the first municipal housing schemes in Port Elizabeth, and of nearby North End. During that period, he was a pupil at various educational institutions now of historical significance in the city such as the Henry Kaiser Memorial School, St Theresa’s Catholic Mission School and Paterson High School. The story of his life also intersects with that of the South African Native College (SANC), now renamed the University of Fort Hare, in Alice in the mid-1940s.

After he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1947, Brutus returned to Port Elizabeth as a teacher – first at St Thomas Aquinas High School in South End (later partially destroyed under the Group Areas Act), and then at Paterson High (eventually relocated from the city centre to Schauderville after a suspicious fire). He then became involved in some of the most influential organisations of that time, including the Teachers’ League of South Africa (TLSA) and the Anti-CAD (Coloured Affairs Department) movement, both aligned to the left-wing Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM). He was one of the key figures, too, behind the ground-breaking though short-lived Coloured National Convention (CNC), and took part in various activities of the African National Congress (ANC) as well. In addition, he was a leading figure behind the formation of the Co-ordinating Committee for International Recognition in Sport (CCIRS), the South African Sports Association (SASA) and its successor, the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (Sanroc).

As a result of his role in some of these organisations, Brutus was banned by the National Party (NP) government in 1961 under the Suppression of Communism Act, which prevented him from attending any gatherings for five years. Soon afterwards, he was suspended – and subsequently dismissed – from his teaching post. As a result, he relocated to Johannesburg at the beginning of 1962 to teach at a private school and to study law as a part-time student at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits University). At the same time he continued to participate clandestinely in various political activities. This did not go unnoticed by the government’s security agencies; his banning order was duly amended, and he was prohibited from publishing any writing as well.

Even these additional restrictions did not deter Brutus. He remained active in Sanroc and, in addition, continued to engage in a wide range of other anti-apartheid campaigns. The consequence of this defiant display of courage and tenacity was inevitable. In 1963, he was arrested when he tried to attend a meeting between Sanroc and the official South African Olympic and National Games Association (SAONGA). When he was released on bail, Brutus reluctantly left South Africa at the instigation of fellow activists – his first attempt to go into exile. However, he was arrested in Mozambique and handed over to the South African security police by their counterparts in the then Portuguese colony. When he tried to escape from custody in Johannesburg, he was shot in the back. After a brief trial, he was convicted on various charges in January 1964 and imprisoned for 18 months – a relatively short but pivotal period in his life.

Before his incarceration, Brutus also made time alongside his various political commitments to write for a number of anti-apartheid national publications such as New Age, Fighting Talk, Contact and The New African; regional titles such as the Durban-based weekly The Leader; and more mainstream newspapers such as the Port Elizabeth daily Eastern Province Herald. He also published poems in various literary journals during this period, including locally in adelphi literary review and in The Purple Renoster, as well as elsewhere on the continent in Penpoint and Transition in Uganda and in Black Orpheus in Nigeria. Further afield, he published poetry in Breathru in the United Kingdom (UK) and in Présence Africaine in France.

In 1962, he won a prize in a poetry contest in Nigeria organised by the University of Ibadan in conjunction with the Mbari Writers’ and Artists’ Club (he subsequently turned it down because the contest was open to black writers only). It was against this background that Mbari’s publishing initiative, Mbari Publications, approached him for more poems with a view to producing a collection of his work. Denis Williams, a Guyanese author and painter who then lived in Nigeria, made the final choice and designed the cover of the book. Brutus’s debut collection, “Sirens Knuckles Boots”, was eventually published while he was in prison in 1963 – the first volume of poetry by a black South African in English in more than two decades …

*****

… [T]his biography places Brutus’s own voice at the centre of its depiction of his life and interior world. His life story is told primarily in, and through, his own words – newspaper and journal articles, tape recordings, interviews, speeches, court records and correspondence. My primary role is to place these personal accounts into a chronological narrative and to provide a context for this narrative. As the South African historian and sociologist Jonathan Hyslop notes: “To place events in a chronological narrative is not necessarily to compile a list of one-damn-thing-after-another. Sequence can have important explanatory value.” …

Brutus’s poetry, too, is a reliable source of information on his interior world. In his own words, “There is only one poet and one person at the centre of all of this and I have consistently said that all my life is of a piece.” Consistently and verifiably, there is a direct correlation between his poetry and his life. In fact, he often chooses to reveal and illuminate his experiences, feelings and thoughts in his poetry rather than through other modes of expression. Poetry, to him, was not an activity separate from his life; it was, in some ways, the very essence of his life. Through his poetry, he conversed with himself, and with the rest of society; it was through his poems that he explored his innermost being, and it was through his poems that he tried to raise awareness about injustice and oppression, and to galvanise opposition to it …

*****

Despite [various] constraints, and notwithstanding Brutus’s own reservations about the merits of a biography on him, constructing an account of his early life remains a singularly worthwhile endeavour. He made a significant contribution to South African literature and, more generally, to South African society during the first half of his life. However, little is known inside his homeland about him during that period. In this sense, the apartheid government’s concerted efforts to immobilise him during the 1960s, and to obliterate any trace of his writing, were largely successful. Not one collection of his poetry was ever published in South Africa.

And yet, even during the NP government’s reign of terror in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre in March 1960, Brutus was never completely silenced. Despite his increasingly stringent banning orders, arrests, imprisonment and house arrests, he continued to publish work in various newspapers and journals during the 1960s – sometimes anonymously, sometimes under pseudonyms or acronyms; sometimes they were articles, sometimes they were poems; sometimes these were published inside the country, sometimes outside …

*****

This biography is an attempt to acknowledge Brutus’s literary and political work and, in a sense, to reintroduce Brutus to South Africa. Other formerly exiled South African writers recognise the importance of such an act of reclamation. The poet Mongane Wally Serote, a former ANC official in exile, describes Brutus as follows: “He was an astute academic; he was a genuine and committed activist; and he believed in being creative through poetry. All of those things combined [were] a major contribution… not only to South Africa, but to the human experience.” The writer Mandla Langa, also once a leading ANC activist in exile, similarly holds Brutus in high regard, especially for his pioneering role in South African poetry. “Dennis is someone that we regarded as an institution, as a national treasure,” he observes. “He opened a lot of doors for people and he really put South Africa, as it were, on the poetic map.”

The South African writer and literary critic Njabulo Ndebele, also, draws attention to the significance of Brutus’s early poetry. He first encountered his writing as an undergraduate English student at the University of Botswana-Lesotho-Swaziland in Maseru and wrote an extended essay on [Brutus’s second poetry collection] “Letters to Martha”. “He just stood out on his own in a particular style and… theme,” recalls Ndebele. “He was an expressive artist at a particular point in time, giving us access to what was not easily available – the inner life of an oppressed people.” But it is not only for the content of his poetry that Ndebele holds him in high esteem; in fact he singles out the original way in which Brutus employed the lyric form as his most important contribution to poetry: “In a sense, some of his poetry is as artistically tight as JM Coetzee’s sparse writing: each word counts; each rhythm counts; each image counts. His best work stood on its own as art more than politics.”

Brutus consistently and imaginatively attempted to reconcile poetry and politics – the two enduring passions of his life. He infused his poetry with politics, and he enriched politics with his poetry. These two realms of human activity – as he often showed so eloquently and powerfully – need not be mutually exclusive. From the early 1950s, he became increasingly engaged in various anti-apartheid activities while, at the same time, continuing to write poetry. He refused to accept fellow South African poet Arthur Nortje’s injunction that “some of us must storm the castles/some define the happening.” He does concede, though, that if he has one regret “it is that I did not devote more time to the craft of poetry; to the use of language, of images, and of cadences; my excuse is that I was busy doing so much else that seemed to be worthwhile”.

Even so, at his best, Brutus wrote poetry of the most exquisite lyrical beauty and intense power. And through his various political activities, perhaps most notably in Sanroc, he played a uniquely significant role in mobilising and intensifying opposition to injustice and oppression – initially in South Africa, but later throughout the rest of the world as well. DM

Dr Tyrone August completed his doctorate on the poetry of Dennis Brutus in the English department at the University of the Western Cape in 2014. He developed and completed most of this biography of Brutus as a postdoctoral fellow in the English department at Stellenbosch University from 2016 to 2018, and is currently a research fellow in the department. He had previously worked as a journalist on various newspapers and magazines for almost three decades, including as editor of the Cape Times and of Leadership magazine. He is a founding member of the South African National Editors’ Forum (Sanef) and a member of the Academic and Non-Fiction Authors’ Association of South Africa (ANFASA).

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.