Maverick Life

Ingqumbo Yeminyanya – a tale as relevant today as it was 80 years ago

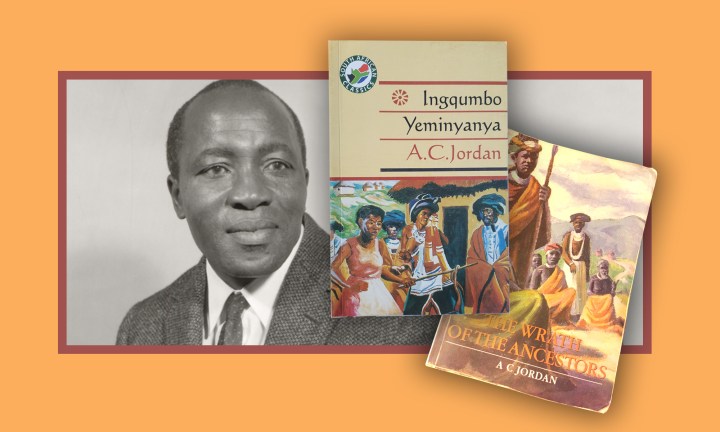

The Lovedale Press’ nearly 200 years in publishing has been incredibly influential in South African literature; the late AC Jordan’s Ingqumbo Yeminyanya is symbolic of the importance of literature written in South Africa’s indigenous languages.

According to a 2013 study by Jana Möller titled The State of Multilingual Publishing in South Africa, “Publishers argue that while the most-spoken home languages are African languages, there is poor reader demand for African-language books, and that it would not be financially viable for them to publish books in these languages.”

The paper also presents statistics for fictional book sales for English, Afrikaans and African Language, noting that, “In a study done by PASA for the period 2008-2010, English fiction ended 31,1% below its 2008 turnover value and Afrikaans fiction ended the reporting period 12,2% above its 2008 value. The turnover in African languages fiction remained low, although it showed an increase of 22,4% over the reporting period”, adding that “the majority of books are for children between the ages of 0 and 14, with a few being for older students or adults. Most of the adult books are for ABET [Adult Basic Education and Training] purposes.”

Ingqumbo Yeminyanya is a case in point, an argument for the important role that works written in indigenous languages play, as mirrors for communities to see themselves, their issues, and their cultural evolution – welcome or contested – reflected and validated.

A few chapters in Maverick Citizen editor Mark Heywood’s 1995 thesis on the historic Lovedale Press’ history, take a look at early 20th-century South African Xhosa author Archibald Campbell ‘AC’ Jordan’s novel Ingqumbo Yeminyanya (The wrath of the ancestors). In doing so, Heywood presents the acclaimed work as a case in point, an argument for the important role that works written in indigenous languages play, as mirrors for communities to see themselves, their issues, and their cultural evolution – welcome or contested – reflected and validated. What made Ingqumbo Yeminyanya a timeless and important body of work is that it “validated the experience of Xhosa people in South Africa,” wrote Heywood.

Jordan was an esteemed scholar who completed his Junior Certificate education at Lovedale College in Alice, Eastern Cape, before moving on to the University of Fort Hare, also situated in Alice, for his Education Diploma and a BA degree. He completed his Masters at UNISA and in the 60s, before his death, he went to the University of Wisconsin at the Institute for Research in the Humanities. He was later awarded a professorship by the US university.

Set in the early 20th century, on the outskirts of the Eastern Cape, South African author AC Jordan’s culture re-setting novel follows Zwelinzima, a young prince of the Xhosa clan, amaMampondomise, who reluctantly leaves the University College of Fort Hare before going back to the land of his ancestors to take his place as king of the amaMpondomise tribe. Conflict arises as his ideas prove to be in contradiction to those of the traditionalists he has to lead; and tension mounts as neither side yields, eventually leading to the tragic end of Zwelinzima’s nascent reign.

“Ingqumbo Yeminyanya is an epic ‘local’ tale. It attempts to represent the dilemmas and divisions experienced by African people (including the author) in a story that is immediate and recognisable to the people the tragedy is about,” says Heywood in the 7th chapter of his dissertation. “It is set within the turbulent space between the clash of currents.” Some of Ingqumbo Yeminyanya’s themes include Christianity versus belief in the ancestors, as well as traditional systems versus capitalism.

In 1940, contradictions between “tradition” and the “new” play out not just in the villages described in the novel, but also in the real-life institutions in the Eastern Cape town of Alice, also portrayed in the novel. For example, the historic Lovedale College relationship with the University of Fort Hare, and how the former started to decline with the presence of a new institution, that now boasts a strong alumni including Can Themba, Dennis Brutus, ZK Matthews and Jordan himself, among other celebrated South Africans. Heywood’s paper shows how the symbiotic relationship between the two institutions is reflected in the early scenes of Ingqumbo Yeminyanya.

At Fort Hare, academics and students perpetuated the nineteenth-century idea that mastery of ‘The classics’ of European literature, especially English literature, was a measure of one’s social respectability and readiness to compete for racial equality in society.

“The Lovedale students eagerly awaited the return of their seniors at Alice station, Zwelinzima was delighted to find that most of his former classmates had moved up to Fort Hare with him… At Fort Hare, academics and students perpetuated the nineteenth-century idea that mastery of ‘the classics’ of European literature, especially English literature, was a measure of one’s social respectability and readiness to compete for racial equality in society.”

As explained by Heywood, Jordan himself arrived at Lovedale College after the close of an intense period of debate between “African students and their missionary teachers about the character and purpose of ‘native education’. But his life was to become a synthesis of the many themes and conflicts that this issue had generated – conflicts that were carried over, largely unresolved, into the twentieth century”.

Heywood further analyses how the novel has links to or is influenced by Shakespeare’s Othello – not only with regard to the tragic themes in the novel, but also the intersection of African literature with European literature, as a consequence of colonization.

Writes Heywood: “The first African novelists, in what became South Africa, all drew heavily on pre-colonial literary traditions both for content and form, but their texts also consciously sought out a relationship with written literature, the models for which all came from overseas.”

He goes on to clarify that “acknowledging the influence of certain English literary texts in African literature in South Africa in this early period does not amount to imposing a negative Eurocentric interpretation on African writing… Jordan was able to appropriate aspects of the English literary tradition and at the same time avoid the danger of creating a Eurocentric text. According to an acquaintance, Jordan ‘devoured the complete works of Shakespeare and the bulk of English poetry and literature’ while he was at Lovedale College and later at the University of Fort Hare.”

Published in 1940 by Lovedale Press, Ingqumbo Yeminyanya was later released in English in 1980 as Wrath of the Ancestors. “Its publication had a profound effect on other African readers and writers. Uncommonly, for a written text of African literature – it is said to be widely read or listened to by or listened to by ordinary African people,” writes Heywood.

The story later found its way onto the small screen as a Xhosa series in the early 90s, and the episodes were screened as recently as 2019 on the now-defunct SABC channel, SABC Encore.

Although Jordan wasn’t alive to see the publishing of the translated version of his novel, he was actively working on translating his work well before his passing. As pointed out in Koliswa Moropa and Amanda Nokele’s paper, Shehe! Don’t go there!: AC Jordan’s Ingqumbo Yeminyanya (The Wrath of the Ancestors) in English, a study on Jordan’s first novel and how he transferred ideas and aspects of culture from isiXhosa into English. “He wanted to introduce the other English-speaking South Africans to African culture and philosophy of life as seen by an African.”

Heywood also argues that, ‘background’ issues do often play a key role in determining the text and context of African literature, that also reinforces the idea that literature is packaged in a way that puts white writers and Eurocentric stories in the forefront of the industry and how we learn about literature.

“The legacy of the first fifty years of Xhosa literary activity is to be respected,” AC Jordan himself acknowledged when reflecting on the African writers who came before him.

Indeed, as interest in South African literature written and published in indigenous languages continues to decline, and pioneering publishing houses such as the Lovedale Press are at risk of closing down, Jordan’s words are even more relevant, for isiXhosa and all nine of South Africa’s official indigenous languages, and the culture and history they carry in their vocabulary. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider