BOOK EXTRACT

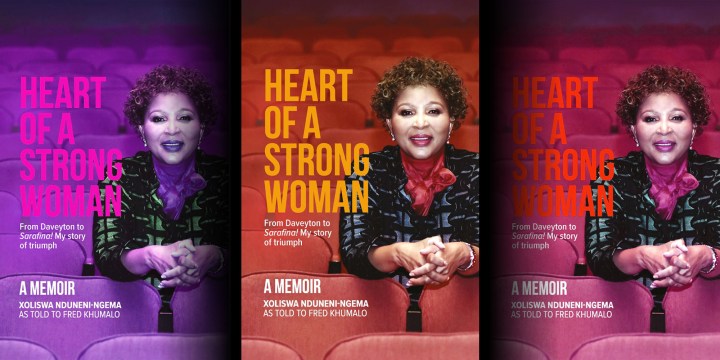

Heart of a Strong Woman: A Memoir

Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema, together with her husband, Mbongeni Ngema, started the production company Committed Artists that birthed the Broadway hit ‘Sarafina!’ Lavish parties with South African legends like Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, first-class trips to New York, and shopping in Paris followed. But beneath the glamour lay a different story – one of constant fighting, cheating, abuse, polygamy and, eventually, a traumatic divorce. Nduneni-Ngema’s story, published by Kwela Books and told to Fred Khumalo, sheds light on an important part of South African theatre history.

Chapter 5: Asinamali!

Let me be honest right away: until I met Mbongeni I was not political at all. Many things that happened in different parts of the country during the 1980s did not make sense to me until Mbongeni explained them to me. For example, I only became aware of the Asinamali! protest after Msizi Dube was killed. It was only after that that I began to put the pieces together and traced the whole matter to its genesis.

Coming home from a JORAC meeting on the night of 25 April 1983, Dube was gunned down outside his house. News of his death swept through the Durban townships in the days that followed, with devastating results.

Angry residents attacked the houses of councillors who were still working closely with the Port Natal Administration Board. One of these was the mayor of Lamontville, Moonlight Gasa, who, at some stage, had been a close friend of Dube’s. Buildings and installations belonging to the government or the administration board were attacked. These included police stations and beerhalls. For the next month, violence raged in Lamontville, Chesterville, Clermont and Hambanathi. Numerous people were murdered.

On 22 June, just under a month after the murder of Dube, the communities around Durban woke up to the news that suspects in the killing of Dube had been arrested. Among them was Moonlight Gasa, the mayor of Lamontville. After a brief trial, Gasa and his accomplices were sentenced to long terms in prison. Gasa died of heart failure on 18 February 1989 while serving time at Westville Prison. He was 58 years of age. All of this is history. As I say, it only came to my attention when I took time to research it because it was relevant to Mbongeni’s next theatrical production.

At the end of 1983, I got my university results. They were atrocious. I was embarrassed. Mbongeni was livid. “You’re wasting my money, and your time!” he told me. He took me out of university and installed us in a rented room in KwaMakhutha township on the south coast. To say staying in KwaMakhutha was a challenge is an understatement. We stayed with a woman by the name of Shorty Ngema. She was no relation to Mbongeni, just the same surname. Shorty was a primary school teacher; she had her own family plus kids but was willing to take us in. This showed me her generosity of spirit even though she was living under tough conditions.

At any rate, while staying in KwaMakhutha I quickly developed a rapport with Shorty Ngema. She told me a few tricks for how to cheat on your man without him knowing you were cheating. There were funny stories about using snuff in your private parts to keep your woman thing tight so that your man never suspected you’d been liberal with your pudenda. It sounded most repugnant! I mean, snuff makes people sneeze endlessly when they inhale it. Imagine the damage it did down there. There were also herbs you were supposed to put in his food so that he lost his appetite for other women. It was called bheka mina ngedwa – literally “have eyes on me only”.

If these truths make your body itch, my dear reader, go and take a shower. And then come back and rejoin me, for I am only getting started. These truths must come out.

Being the level-headed young woman that I was, I listened to Shorty’s stories carefully, but never considered them useful to myself. I did not intend cheating on my husband, so I had no use for snuff in my private parts. I also did not believe any medicine would make him stop cheating. I simply had to work hard on my marriage. It was still new, young and fragile, after all. But my conversations with Shorty made me realise that I had finally entered this huge, complicated forest called adulthood. How I navigated this forest, how I fought against the snakes and other creatures that lurked in the deep thickets, how I cut through the forest would determine the kind of adult I would become; the kind of woman I would become. And I knew I had to fight to keep standing on my feet. Even though I didn’t realise it then, it became clear to me that I had to fight against Mbongeni, the man I loved, in order to keep my sanity; in order to keep our marriage intact. That’s not a contradiction. I had to fight in order to protect what we had.

Mbongeni was due to go overseas once again, for yet another performance of Woza Albert! I was so thrilled to join him this time on his trip to New York City. We stayed at the house of Duma Ndlovu, a journalist and playwright originally from Soweto. The house was a stopover for most South African artists trying to find their way around America.

Duma, a charming, gregarious man, had left South Africa at the height of the student uprisings of 1976. In the United States, he had gone to university, earned himself a degree. By the time we got there, he was pretty well established and highly respected in artistic circles over there. Before I knew it, I had spent six months in New York. During our stay there, I was not allowed to go anywhere alone because, according to my husband, American men would snatch me. So I stayed at home. I cooked meals from South Africa, meals which were popular with Duma and his friends who were missing home. The beautiful thing about staying in New York at that time was that I went to the theatre every day. I got so immersed in the play, I knew almost all the lines.

One wonderful, unforgettable and absolutely beautiful thing happened to me – to us – during that stay. Mbongeni arranged for us to renew our vows at Duma’s house. He had clearly put a lot of thought into this and arranged everything. The place was packed with friends, mostly South Africans in exile. It was so moving, so romantic, so human, so full of warmth. Mbongeni had not forgotten that back in 1981 when we got married, we had done everything at the magistrate’s court. There hadn’t been any guests. We hadn’t had a white wedding, which was the norm in the township. And we hadn’t gone to any church. I did not come from a religious family myself, but having gone to St John’s College I had developed a relationship with the church. I was not religious per se, but I always knew that there was a superpower somewhere, looking over us, directing our destinies. You might say I was spiritual. So that ceremony was for me a coup on Mbongeni’s part. He had hit the bullseye.

Then it was time to come back home to South Africa. We found a house in Umlazi township, E Section. The house was completely bare of furniture. Because there was still not much money to go around, we had to make do with the most basic. For food we ate pap and tinned pilchards most of the time. In our bedroom, we got six ash bricks, on which we put an old door and placed a mattress on top of it. With blankets and a bedspread, you could not tell that there wasn’t actually a real bed underneath.

Like many people in the neighbourhood, we used candles for illumination and cooked our meals on a primus stove. The smell of paraffin from the stove reminded me of the paraffin-soaked bread in Nzimankulu. But I decided to bear these temporary inconveniences with fortitude. My eye was on the prize. I knew Mbongeni was about to strike it rich. I could feel it in my bones that we were about to turn the corner. Mbongeni stayed with me for a longer period this time.

It was during this long sojourn that we sat down and spoke at length about the future of his career. The talks resulted in the formation of our theatre company, Committed Artists. The first production for this company was to be a play inspired by and based on the Lamontville rent protests which had culminated in the murder of Msizi Dube.

Before Mbongeni left for overseas again, he managed to put together a cast of five young men to start rehearsing this new play (which did not have a name as yet). Thankfully, these were people I knew and trusted and I could therefore share the house with them without fear. They included Mbongeni’s younger brother Bhoyi, and Bheki Mqadi, who had been introduced to me I think the previous year. Apart from Bheki, who had acted in a play called Too Harsh, the other four players had no theatrical experience whatsoever.

Mbongeni was doing exactly what his former boss Gibson Kente had been doing over the years – taking youngsters straight from the street and moulding them into stage dynamos. Between legs of Woza Albert! Mbongeni instructed his new cast in Gibson Kente’s vocal drills and Grotowski’s physical exercises. Like Kente, Mbongeni did not put much emphasis on a written script. He preferred spontaneity, improvisation. DM

Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema is the CEO of the Joburg City Theatres (Joburg Theatre, Soweto Theatre and Roodepoort Theatre). She is also the former CEO of the South African State Theatre and former MD of Bassline. Xoliswa has a social science degree from the University of KwaZulu-Natal and lives in Joburg.

Fred Khumalo is the author of 11 books, his latest work being “The Longest March”. He holds an MA Creative Writing from Wits University and is a PhD (Creative Writing) candidate at the University of Pretoria.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider