Maverick Citizen & Spotlight Exclusive

Leaked government strategy document shows billions needed to avert healthcare worker crisis

A new government strategy, obtained by Spotlight and Maverick Citizen, estimates that billions of rands in additional investment is needed to improve staffing levels and equity across South Africa.

South Africa’s much-anticipated 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy document raises the possibility of severe public sector healthcare worker shortages by 2025. The new strategy, obtained by Spotlight and Maverick Citizen, estimates that billions of rands in additional investment is needed to improve staffing levels and equity across provinces.

The strategy, titled “2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy: Investing in the Health Workforce for Universal Health Coverage”, was developed by a ministerial task team and will, once officially adopted, replace the government’s previous Human Resources for Health Strategy that expired in 2017. The new strategy can be downloaded here.

Worsening healthcare worker shortages

Describing the country’s fiscal and economic outlook as “bleak”, the strategy states: “Various analyses indicate a current and projected shortage of skilled health professionals in South Africa. Due to population growth alone, the shortfall in essential health workers will worsen by 2025 if health workforce expenditure only increases in line with inflation.”

According to analysis presented in the strategy, an additional 97,000 health workers, with community healthcare workers (CHWs) making up about one third, will be needed by 2025 to address inequities across provinces. A second analysis estimates bringing primary healthcare services up to scratch will require an estimated 88,000 additional primary healthcare workers by 2025.

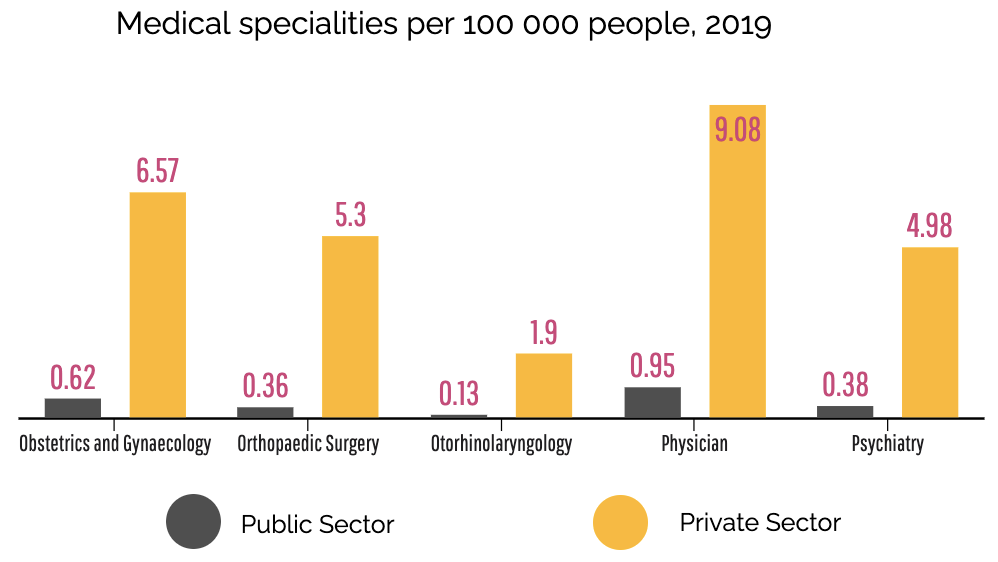

The strategy points to huge disparities between the public and private healthcare sectors which are projected to worsen without immediate policy intervention. It states that the overall national density of medical specialists was calculated as 16.5 [specialists] per 100,000. However, there are an estimated seven specialists per 100,000 population employed in the public sector and 69 per 100,000 in the private health sector.

Within the public sector, severe inequities exist both between provinces, and between rural and urban areas, with rural areas having significantly lower numbers of more skilled health professionals (notably specialists, nurses and CHWs).

“The Western Cape has 25.8 medical specialists per 100,000 public sector population compared to only 1.4 per 100,000 in Limpopo. Although the location of public sector tertiary and central hospitals influenced this maldistribution, in practice this means that accessing specialist services in Limpopo is extremely difficult in comparison to other provinces,” the strategy states.

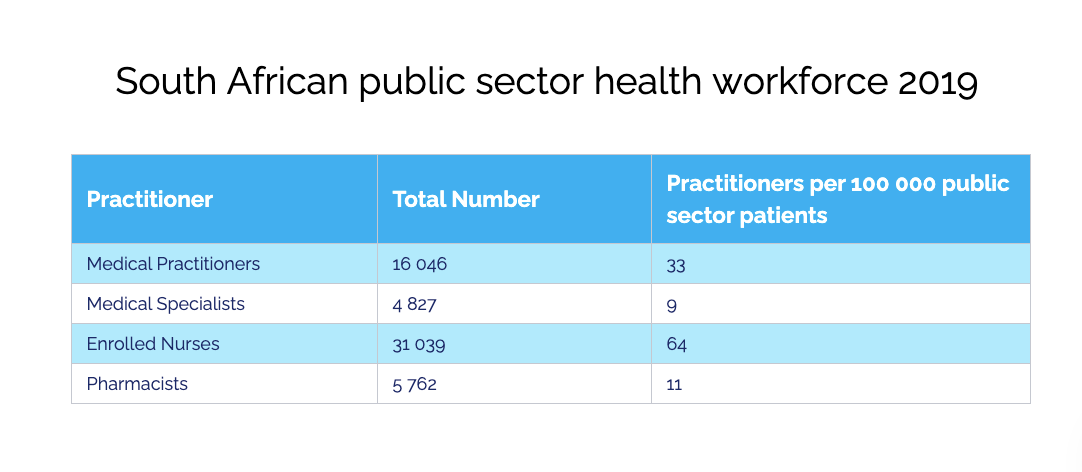

In 2019, the public sector employed 243,684 health workers in 22 selected categories. Of these, nurses make up the largest proportion of the health workforce at 56%.

“In total, there are nearly 503 health workers for every 100,000 public sector users,” according to the strategy. “The density for all nurses combined is 282 per 100,000, whereas there are a total of 43 doctors and 30 allied health workers per 100,000 public sector population. The figure of 112 per 100,000 for CHWs equates to one CHW for every 895 members of the population.”

Modelling the current and future need for healthcare workers

Modelling the current and future need for healthcare workers

To better anticipate South Africa’s future need for health workers, the strategy includes projections from three different models using different methods. (For more detail on these projections and the limitations of the models, see the full strategy linked above.)

The first model estimated what investments the country needs to make to get healthcare worker staffing levels in the bottom six ranked provinces up to the level of the third-ranked province (a so-called equity target). They found that “96,586 additional health workers will be needed at an additional cost of nearly R40-billion to meet the third-ranked province equity target by 2025. An additional 14,791 health workers and an additional R8.1-billion would be required by 2025 to keep densities at 2019 levels (status quo).” According to this model, a shortage of around 16,000 professional nurses needs to be addressed to reach the equity target by 2025.

A second model attempted to estimate the health workforce needed to deliver improved primary healthcare (PHC) services in the public sector. They found that “[to] increase the PHC utilisation rate to 3.2 [facility visits per person, per year, excluding medicine collections] would require 186,362 staff members at a total cost to employer of R54.6-billion in 2019. (…) By 2025, the required number of health workers would be 202,740 FTEs [specialists] at a total cost to [the] employer of R75.1-billion. That represents a gap of 87,614 health workers which would require an additional budget of R34.3-billion to employ.”

A third model estimated the supply and need of medical specialists with a view to inform planning for medical specialist training. The model includes both the private and public sectors, and encompasses 26 specialities and 44 sub-specialities. “Based on a novel linking of several datasets, the study estimated that there are currently 9,731 specialists (FTEs) in South Africa which is considerably less than previous analyses by the South African Health Review 15,008 (2015), the Health Professions Council of South Africa 12,776 (2018) and Econex 10,585 (2012).”

Here also, the projections made for grim reading. “Overall, significant increases in the number of specialists are required by 2025, most targets are 2-3 times the projected availability of specialists. The inequity between the public and private health sectors is projected to persist, and this requires specific policy intervention to ensure greater specialist availability in the public sector, and specific specialities,” the strategy states.

Goals and recommendations

The strategy identifies five goals accompanied with a set of recommendations. The five goals are:

- Goal 1: Effective health workforce planning to ensure human resources for health (HRH) aligned with current and future needs.

- Goal 2: Institutionalise data-driven and research-informed health workforce policy, planning, management and investment.

- Goal 3: Produce a competent and caring multi-disciplinary health workforce through an equity-oriented, socially accountable education and training system.

- Goal 4: Ensure optimal governance; build capable and accountable strategic leadership, and management in the health system.

- Goal 5: Build an enabled, productive, motivated and empowered health workforce.

Some notable recommendations in the strategy include that:

- A functional National Health Workforce Analysis and Planning Function should be established to institutionalise and strengthen planning,

- The national department of health (NDoH) should establish a Health Workforce Consultative and Advisory Forum (HWCAF) to consult and get inputs, and advice from a wide range of stakeholders from all spheres of government, health professions councils, the private health sector, academia, social partners, and relevant civil society organisations,

- An overarching national HRH monitoring and evaluation framework that covers all levels of the health system must be developed,

- The desirability and feasibility of a unified council for all health professionals should be investigated, and

- The NDoH should embark on an urgent review of Remunerative Work Outside the Public Sector (RWOPS), its interpretation, application and management.

While the strategy contains some estimates of what it will cost to employ the required numbers of healthcare workers, it does not include a full costing of what it would cost to implement all the strategy’s recommendations.

Where the strategy came from

In March 2019, the Minister of Health appointed a ministerial task team “to support the NDoH with the development of a HRH Strategy for 2030 and an associated Strategic Plan for the five-year period from 2020/21 until 2024/25”. South Africa has effectively been without an overarching strategy in this area since the HRH Strategy for the Health Sector 2012/2013 – 2016/2017 expired.

Professor Laetitia Rispel of the University of the Witwatersrand chaired the task team, which included various leading academics, members of civil society, and senior government employees such as Dr Gail Andrews, Deputy Director-General for Health Systems and Integration and Human Resources for Health, and Gcinile Buthelezi, Director for Human Resources for Health.

The task team started its work in April 2019 and a year later, in March 2020, a final strategy was with the NDoH.

The strategy was obtained by Spotlight and Maverick Citizen five months later in August 2020 from multiple sources. We understand that the strategy has been presented to and endorsed by the National Health Council’s (NHC) Technical Committee, but that it has since been stalled.

Responding to Spotlight, spokesperson for the NDoH, Popo Maja, said that the strategy had not been made public yet as it first had to be approved by the NHC. Maja said the strategy could not be tabled to the NHC due to the Covid-19 pandemic and that all NHCs have since focussed on the pandemic. He did not indicate when the NHC would approve and publish the strategy.

“Notwithstanding the delay in publishing the 2030 HRH Strategy, implementation of some of the recommendations proposed in the strategy is in progress and in some instances, has been preempted by the need for an urgent response to the Covid-19 pandemic. e.g filling of vacancies in the health system, recruitment of additional clinical capacity, development of a Human Resources for Health Information System, strengthening of systems for in-service training and dissemination of information to health care workers,” says Maja. DM/MC

This article was also published on Spotlight

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider