AHEAD OF 2024

Experts wrestle with the nature of changes to South Africa’s electoral system

Two years is a short time in electoral politics, but this is how much time MPs have to change the way we vote. Some experts got together to try to come up with proposals.

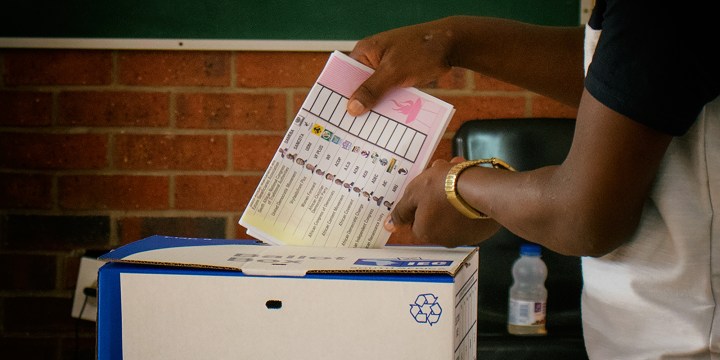

The 2019 general elections were the last of their kind in South Africa, but nobody knew this at the time. Voters turned out at the polls in smaller numbers than ever in democratic South Africa.

In June, almost a year after the ANC was again declared the winner of the 2019 national elections, but with a reduced parliamentary majority, the Constitutional Court ruled that the Electoral Act was unconstitutional. It gave legislators two years to amend the act to allow independent candidates to run in provincial and national elections.

This means the 2024 elections will be different, but just how different is still a matter up for debate.

“It is an interesting opportunity that the Constitutional Court has created,” says the In Transformation Initiative director, Roelf Meyer. “Parliament has to complete this within 24 months and we have taken good advantage of the opportunity to do some real thought-provoking research and debates, to see how we can contribute.”

Meyer and In Transformation Initiative CEO Daryl Swanepoel have convened a panel of experts for this purpose, and it includes academics, elections practitioners and the former chairperson of the Independent Electoral Commission of South Africa, Brigalia Bam. The group is set to hold its third meeting on Monday 25 August, and the aim is to come up with a proposal containing two or three models that could be submitted when Parliament opens the process for public comment.

Meyer, a former minister of constitutional development and the chief negotiator for the National Party-led government during the democratic transition in South Africa in 1994, says it’s best not to tinker with the Constitution itself to effect these changes.

“So far we [the panel] take cognisance of the provisions of the Constitution, which says the system of election will be proportional, with the emphasis on ‘in general’,” he says. “This is something that we still have to clarify in our minds, what this ‘in general’ means.”

Political parties, and indeed voters themselves, in 2003 missed an opportunity to reform the elections system when the majority proposal of the commission led by former politician Frederik van Zyl Slabbert was rejected. The commission said a mixed system with proportional representation as well as the direct election of constituency representatives was preferable, but Parliament opted to make permanent the interim system of proportional representation that had governed national and provincial elections since 1994.

Now the MPs have no choice other than to make changes, and these could be extensive or they could be minimal. The judgment wasn’t that prescriptive.

Unhappiness among members of the establishment with the election of rape- and corruption-accused Jacob Zuma as president in 2009 led to numerous debates about changing the electoral system so that South Africans could elect a president directly, instead of in effect relying on the majority party to do so.

One of the panel members, Jorgen Elklit, a professor at the Aarhus University in Denmark who also served on the IEC in 1994, previously remarked that South Africa’s electoral system is possibly the most proportional system in the world.

Meyer says this isn’t necessarily a good thing, but the same could be argued for a first-past-the-post system.

“That is why this is an important exercise that we are involved in at the moment. We were trying to take into account the fact that the weakness of our current system is that there is not sufficient representivity, and not sufficient accountability because of the party system and the way it is applied.”

Meyer says the original idea behind a proportional system was that it would represent minorities and smaller parties better, but during the negotiations there was also not enough time to fully consider going any other route.

“At that stage, there was just not enough time to do a proper exercise to establish constituencies,” he says. “If we went the route of constituencies at that stage, it would have been a failed exercise, but it was in the back of the mind to say, ‘Let’s revisit this subject in the time to come’.” Personally, he says, he’d have preferred for this revisiting to have happened much earlier.

The current proportional representation system gives parties a lot of power, because it means candidates have to please the party to stay in office or on the list. It’s not impossible that political parties could drag their feet with the Electoral Act amendments. In that respect, Swanepoel says, after the panel comes up with models it would test these with the broader public so that when these models are presented to the parties, the panel could convey the public’s sentiments about these as well. It’s also hoped that an improved electoral system that would allow voters to hold politicians directly accountable would encourage more voters to participate and stem the decline in turnout.

“The lack of a face and a person representing me as an individual is the biggest frustration with voters, and one hears that quite often. People don’t know where to file their complaint. They send it to the party offices and never hear anything back, and that is where the constituency system has value,” Meyer says.

Another panel member, Ebrahim Fakir from the Auwal Socio-Economic Research Institute, has previously pointed out that a constituency-based system doesn’t automatically bring about accountability or responsiveness, as is evident in Zimbabwe.

Unhappiness among members of the establishment with the election of rape- and corruption-accused Jacob Zuma as president in 2009 led to numerous debates about changing the electoral system so that South Africans could elect a president directly, instead of in effect relying on the majority party to do so.

A provision that would allow independent candidates to run for office could, theoretically, make this happen, but experts seem to agree that the possibility is slim that the changes effected will be quite that extensive. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider