South Africa has endured over 100 days of Covid-19 lockdown and has passed 500,000 infections. In addition to the health crisis, the country is also facing an economic crisis, which could potentially lead to mass starvation. Despite this dire state, the governing kleptocracy continues to loot unaffected, even feeding on the funds made available for Covid-19 relief.

While President Cyril Ramaphosa has decried the corruption and set up a joint anti-corruption centre (comprising the Hawks, National Prosecuting Authority, the South African Police Service, Special Investigating Unit and the Independent Police Investigative Directorate), indications are that the ANC is unwilling and unable to halt the endemic lawlessness.

Broad church

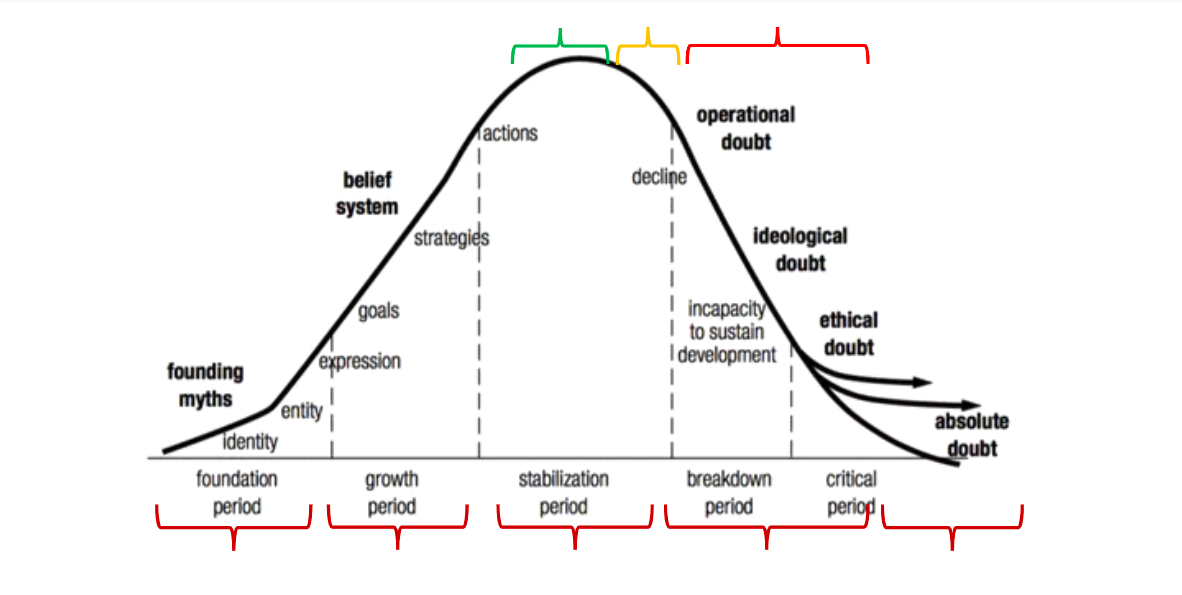

The ANC often proclaims itself to be “a broad church” and therefore, to understand how the ANC reached this sad state, it is useful to consider the party’s progression over a typical ideological lifecycle. As can be seen from the diagram below, the ANC has experienced three phases:

The first was during the foundation and growth phases, when the founding principles and beliefs coalesced. This period also encompassed the formation of the youth league and Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), the adoption of the Freedom Charter, and the long years of the struggle.

The second phase was much shorter and includes the post-1994 stabilisation government of national unity during the President Nelson Mandela years until 1999 and followed by ANC rule under President Thabo Mbeki. This period was initially marked by the ANC’s manifestation of the ideological tenets that had been adopted in prior decades. However, the tipping point from stabilisation to breakdown started with the early scandals – including the Sarafina debacle and the Arms Deal – and quickly gathered pace with Mbeki’s disastrous HIV/Aids denialism.

The third phase marks the ANC’s rapid decline as its ability to deliver on its promises, abide by its own founding principles and willingness to act as an ethical leader of society were eroded by service delivery failure and corruption, culminating in State Capture during the President Jacob Zuma years. This stage was characterised by the ANC’s inability to transform itself from a liberation movement into a democratic political party and it consequently suffered from many of the common symptoms of an atrophying liberation movement.

Similar to the national liberation governments in other Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries, these can be ascribed to the structural and cultural limitation of waging a liberation struggle, and the limitations associated with the compromises reached during negotiated settlements. While it was initially hoped that this cycle would halt or reverse with the ascendancy of Ramaphosa, the reality is that the ANC has been unable to reclaim its position of trust among South Africans and the alliance partners.

(Based on source: Cada, L., Fritz, R., Foley, G. and Giardino, T. Shaping the Coming Age of Religious Life, Seabury Press, New York, 1979: 53, 78)

Eat first

The disparity between the ANC’s ideological founding principles and its current ethical bankruptcy becomes wider with the passing of each stalwart – as recently evidenced by Zuma being asked to speak at Andrew Mlangeni’s memorial. The most apparent evidence of the ANC’s ethical decline has been the burgeoning kleptocracy that has developed over the course of the last two decades.

As noted by academic studies, corruption can facilitate (“grease the wheels”) or hinder (“sand in the wheels”), economic development. The abuse of ANC policies, such as black economic empowerment and cadre deployment, have given rise to tenderpreneurship, patronage and nepotism. While this has poured sand in the wheels of socioeconomic upliftment, service delivery and private sector investment; it has greased the wheels of ANC cadres, their family members, and associates. The ANC has therefore become the centre of a shadow economy.

Two years after “Ramaphoria”, indications are that the faction of the ANC aligned to Ramaphosa has been unable to reverse the entrenched corruption in the ANC. While the party’s ethos is based on collective leadership, increasingly this has translated into collective inaction and collective unaccountability.

Implications

South Africa’s opposition parties are still shaped around socio-cultural identity politics and have therefore been unable to form a coalition that can challenge the ANC’s historic political hegemony. The danger, therefore, is that as the ANC dies, so will the country’s young democracy. Consequently, it will increasingly be up to civil society organisations and international financial institutions to safeguard South Africa’s democratic institutions and hold the ANC to account.

As the ANC’s unwillingness to act against its corrupt members becomes ever more apparent, it is increasingly likely that Ramaphosa’s popularity will continue to decline. Indications are that it will not be long before the ANC’s broad church and voter support collapses into absolute doubt. This does not bode well for the likelihood of Ramaphosa serving a second term in office, paving the way for the Zuma-aligned faction to try to take control of the party once again.

At that stage, South Africa will have little choice other than to accept a large conditional bailout from the International Monetary Fund. As history shows, this will then likely include some form of structural adjustment programme with its accompanying cuts in public sector employment and wages, privatisation of state-owned entities, labour market reforms, and monetary and broader fiscal policy interventions.

This will naturally lead to significant socioeconomic and political instability as the country’s economic foundations are reshaped, and South Africa’s second republic comes to an end. DM

Sean Gossel is Associate Professor in Financial Economics at the Graduate School of Business (GSB), University of Cape Town.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider