BUSINESS MAVERICK ANALYSIS

Dollar’s diminishing safe-haven status is a benefit to emerging markets

Investors have been rushing to the sanctuary of gold and alternative safe-haven currencies instead of the dollar, which reached a 22-year low. Low US bond yields, political uncertainty ahead of the elections and concern about the difficulties the US is having in getting the pandemic under control are all weighing on the greenback.

The dollar and US government bonds have been losing their appeal as safe-haven investment destinations of late. Instead, gold and alternative currencies, like the Swiss franc and Japanese yen, have become preferred sanctuaries for investors looking to shelter from the economic fallout from Cobvid-19.

Over the past week, trends that had already begun to appear in financial markets accelerated. The dollar fell to a 22-month low and general consensus is that the world’s reserve currency may remain under pressure for some time to come. Gold surprised even the most optimistic expectations when it broke through $1,900 – a record high – and headed towards $2,000 before taking a breather.

All this as the global number of Covid-19 cases passed 16 million last week, US infections are closing in on 4.5 million, and new cases arose in countries that were thought to have overcome the virus. The Bureau for Economic Research notes that the trajectory of the virus exacerbated concerns that the Covid-19 crisis may be prolonged.

Concerns about the sustainability of a nascent US economic recovery appears to be undermining the value of the dollar after jobless claims rose last week in one of a number of signs suggesting cracks are appearing in the US economy as states pause or roll back the reopening of businesses.

Historically low interest rates are not helping the dollar’s cause, as investors seek better yields elsewhere – and are finding them in emerging markets. Right now, the risk-return dynamics seem to be erring on the side of the other safe havens instead of US assets, with emerging markets benefiting from the side currents.

The Japanese yen, which has had its own share of health and economic challenges, appreciated to a four-month high of ¥105.35 per dollar, with some predicting it could continue moving to the psychologically significant ¥100 level last seen in 2016.

In his article “Why Japanese yen is still one of the safest places to park your money in a market crash”, Alexis Stenfors, a senior lecturer in economics and finance at the University of Portsmouth, says:

“The Japanese yen has been a favourite in recent times. The Swiss franc is another, with Switzerland’s long history of low inflation and political financial stability. But the yen has the added attraction of being more liquid, meaning it is more readily available to trade.”

For Stenfors, “A safe haven is not a theoretical construct, but the place where traders and investors seek shelter in practice when all options have been explored – including all the halfway houses.”

He adds that although the US dollar “remains the undisputed global reserve currency”, it is more telling what investors actually do in a crisis. He points out that after the 9/11 attacks, the Madrid bombings, the Lehman collapse, the eurozone crisis and the Brussels bombings, traders and investors bought Japanese yen instead of other currencies, including the dollar. He believes the March 2020 market crash confirmed that the yen is still “the safe-haven currency par excellence”.

At the heart of the dollar’s weakness is US Treasury yields that have become unappealing at their current low levels and are likely to remain so for the next couple of years. The Federal Reserve has been pretty explicit in its guidance in this regard and is expected to reiterate its accommodative stance in its July statement released this week. US Fed chairperson Jerome Powell has already indicated the bank is “not even thinking about thinking about raising rates”.

Should the current monetary policy stimulus still not prove sufficient to buoy the economy, the Fed would have to decide whether to opt for negative interest rates, which is viewed unlikely, or whether to introduce yield curve control, a route considered distinctly possible but a decision not to be taken lightly.

The guidance given after the July Fed meeting is expected to reinforce the lower-for-longer positioning of the Fed. However, it is not expected to reveal any significant change in monetary policy stance until its September meeting.

UBS agrees the reduction in the US rate advantage is a contributing factor to the depreciation in the dollar.

“We expect broad-based depreciation of the US dollar, but we see particular upside potential for sterling, the Swiss franc, and gold.”

The good news for South Africa is that a weaker dollar – long may it last – would also provide some relief in the size of the repayments the government will need to make on the $4.2-billion (R70bn) IMF emergency Covid-19 loan facility approved this week.

Another factor that could sustain the weakness in the months to come is political uncertainty ahead of the presidential election in November.

Gold has been the most visible beneficiary of safe-haven investor demand. UBS notes that, along with being a commodity, gold also functions as a currency.

“Since gold is denominated in dollars, the precious metal tends to appreciate when the US currency weakens. As a non-yield-bearing asset, gold also benefits from low or negative real interest rates that reduce the opportunity cost of holding the asset.”

Participants at the UBS Investor Forum also viewed the US election as a risk and felt greater political fragmentation would increase the need to diversify investment exposure. US-China relations were seen as another key risk. Tensions ratcheted up another level last week when the US government ordered the Chinese consulate in Houston, Texas to close its doors and the Chinese responded by ordering the closure of the US embassy in Chengdu.

Against this backdrop, most of the participants at the Investor Forum expected the dollar to weaken further and agreed that it would be a positive for emerging markets.

At the surface, it may seem counterintuitive that emerging markets could benefit at a time when most developing countries face considerable economic challenges as a result of the pandemic. Perhaps the headline of a New York Times article in May, “The Markets are not the Economy”, captures it best and, as such, investment flows at times bear no relation to fundamental economic realities.

However, there is academic support for a weaker dollar historically benefiting emerging markets for extended periods. An international finance discussion paper published by the US Federal Reserve and authored by Samer Shousha finds that “currency appreciations against the dollar lead to easier financial conditions, compressing sovereign bond spreads, and increasing dollar-denominated cross-border bank flows, which then lead to higher real investment.”

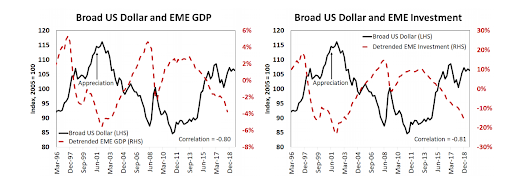

As the graphs below show, since March 1996, whenever the broad US dollar depreciates, emerging market GDP and investment inflows accelerate.

Within the current environment, however, there is no guarantee the 80% negative correlation between the dollar and emerging market GDP and investment flows will hold firm as risk appetite waxes and wanes on fast-changing investor sentiment regarding the health and economic progress made by emerging markets.

In the interim, South Africa has experienced the benefits of the dollar weakness over the past week, with the rand appreciating slightly, and the bond market experiencing inflows of R1.5-billion. The real yield on 10-year bonds has moved even higher to 7.1% after inflation fell to 2.1% in May. The risk premium priced into South African local bonds (the SA 10-year government bond trading at 9.2% relative to a US 10-year bond at 0.59%) is 8.6%.

The good news for South Africa is that a weaker dollar – long may it last – would also provide some relief in the size of the repayments the government will need to make on the $4.2-billion (R70bn) IMF emergency Covid-19 loan facility approved this week.

But it is difficult to predict how long the dollar weakness will last and whether the greenback’s safe-haven status will incur any lasting damage as long as US interest rates are close to zero and if the Fed does resort to yield curve control, capping Treasury yields to further stimulate economic activity. BM/DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider