BOOK EXCERPT

The Pink Line: The World’s Queer Frontiers, the new book from Mark Gevisser

From refugees in South Africa to activists in Egypt, transgender women in Russia and transitioning teens in the American Midwest, Mark Gevisser’s The Pink Line folds the intimate stories of individuals, families and communities into a definitive account of how the world has changed so dramatically in just a decade.

Mark Gevisser’s new book follows protagonists from nine countries all over the globe to tell the story of how “LGBT Rights” became one of the world’s new human rights frontiers in the second decade of the twenty-first century.

This eye-opening book is crafted out of six years of research and reveals a troubling new global equation that has come into play: while same-sex marriage and gender transition are now celebrated in some parts of the world, laws to criminalise homosexuality and gender non-conformity have been strengthened in others.

The Pink Line is a work of great scope and wonderful storytelling by the winner of the Alan Paton Award; a groundbreaking account of how issues of sexuality and gender identity divide and unite the world today.

Read the following excerpt from Mark Gevisser’s The Pink Line:

***

A Debt to Love

“Gays Engage!”

This was the front-page headline of the Nation newspaper, from the central African country of Malawi, on Sunday, December 28, 2009. Above it was a photograph of two people, bleary and uncomfortable in matching his-and-hers outfits cut from the same patterned wax print: “Gay lovebirds Tiwonge Chimbalanga and Steven Monjeza on Saturday made history when they spiced their festive season with an engagement ceremony (chinkhoswe),” the article read, noting that this was “the first recorded public activity for homosexuals in the country.” Down the left side were some helpful “fast facts”: homosexuality was “illegal in Malawi” and carried “a maximum sentence of five or 14 years imprisonment . . . with or without corporal punishment.”

Aunty moved in the determined manner of someone who might collapse if she did not keep her chin forward.

Four and a half years later, in May 2014, I looked at this page with Tiwonge Chimbalanga: she had brought it into exile with her, across three thousand kilometers and four countries, and tacked it onto the corrugated-zinc wall of her shack in Tambo Village, a township outside Cape Town. Although she displayed it, she objected to it, too: “I am not a gay, I’m a woman,” she said to me in English, before reverting to her native Chichewa: “They told me I was gay when they arrested me. They told me that I was paid to do my chinkhoswe by LGBTs from overseas. But the first time I heard the word gay was when I saw it next to that picture and when the policemen came and took me away.”

When I had arrived earlier, Aunty—as Chimbalanga was universally known—had been waiting for me on the street in an elaborate purple ensemble with full skirts and turban, the kind of confection usually reserved for a chinkhoswe back home. I thought she might have made the effort because she was receiving a visitor, but it turned out this was how she always dressed, so very much at odds with the Lycra-leggings style favored by local women in this sandswept proletarian place. Aunty was tall and very dark with broad features and would have stood out anyway, even if she did not wear thick foundation to cover her facial hair, which gave her skin a silvery sheen. She was brittle, and regal, with a studied haughtiness, but I saw how quickly this could evaporate into a kind of girlish bashfulness when she was more relaxed, or when she had cause to remember her life before people told her she was gay and took her away.

Aunty moved in the determined manner of someone who might collapse if she did not keep her chin forward. In her low-heeled silver pumps, she led me along a sodden narrow path between shacks to her own, one of several in the yard behind a big house. Aunty’s was the nicest by far, thanks to the relief aid she received from Amnesty International as a released “prisoner of conscience.” She had a large television, a sound system, and a coterie that included her “husband” of about a year, Benson, an unemployed Malawian compatriot who lived with her. Neighbors popped in constantly to cadge a tomato, or to buy some of the beer she sold on the side. “Aunty! Aunty!” they exclaimed, somewhere between affection and mockery, as they passed her locked security gate.

I had brought a meal: a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken and a magnum of Mountain Dew. Benson was a small, mild man, quietly inebriated, and seemingly dominated by Aunty. She ordered him to unstack some plastic chairs and she smoothed, it seemed to me, an imaginary cloth out over the table that filled one of her two rooms. Taped somewhat randomly along the wall alongside the “Gays Engage!” page were photographs of her with people who appeared to be her lovers and friends, and other articles detailing her imprisonment and release back home. These were interspersed with adverts carefully cut from South African magazines, tending toward a girlie-on-a-sports-car hyperfemininity. A code had been carefully written with black marker across the front of the oversize fridge: “ROMA 13 8.”

I asked what this meant.

Aunty reached across the table for the tattered green Bible she had been gifted by her most regular visitor in jail back in Malawi: a priest who urged her to repent. She opened it to Romans 13:8, and read the verse aloud, with some difficulty: “‘Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for whoever loves others has fulfilled the law.’”

Why had she chosen to write those words on her fridge?

“These are the words that were printed on the card at my engagement ceremony,” she said in Chichewa, through her friend Prisca, another Malawian refugee; Aunty struggled with English even after four years here. “I want all visitors to my home to know what love means. Then they will know I did nothing wrong.”

***

My new book is Aunty’s story, and that of others from different parts of the world who have found themselves on what I have come to call the Pink Line: a human rights frontier that divided and described the world in an entirely new way in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. No global social movement has caught fire as quickly as the one that came to be known as “LGBT”: the worlds Aunty and I inhabited in 2014 were unimaginably different from how they had been for each of us, from such very different places, even a decade previously.

Our post-apartheid constitution was famously the first in the world to guarantee equality on the basis of sexual orientation.

Aunty’s home in Tambo Village is not twenty kilometers from the handsome century-old bungalow, overlooking the ocean at Kalk Bay, where I wrote my book. My husband, C, and I bought it in 2012; we were married three years earlier, in 2009, the same year that Aunty held her chinkhoswe. But while her commitment ceremony brought her abject humiliation, a fourteen-year jail sentence, and a life in unwanted exile, mine got me a much-desired few years in Paris, spousal benefits from C’s job, and the same rights as any other married couple in South Africa. Our post-apartheid constitution was famously the first in the world to guarantee equality on the basis of sexual orientation; ten years later, in 2006, South Africa became the fifth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. Here we were, a married gay couple, the beneficiaries of rights in a way I could not have imagined when I was a young man.

Three decades previously, a steely defiance cloaking my terror, I had come out to my own parents at the age of nineteen. They were supportive, but my father could not hide his concern: Would I ever know the joys of family? Would I lead a lonely life? I had fought my corner: of course I could have children; of course I would find love. But it was 1983—there was not yet even an Internet to provide me with the ammunition of information and the solace of a virtual community—and I struggled to convince myself. Then, as I was opening into adulthood, the AIDS epidemic descended, with its cruel confirmation of everything gay men had been taught to believe about ourselves: we were sinners and we were being punished; our sexuality was morbid and we would die.

Through all of this I came to believe, fervently, that I and others like me had the same right to live openly as anyone else, and I did my bit to fight for this. As an undergraduate in the U.S. in the 1980s, I took on the mantra of Harvey Milk, the gay San Francisco politician assassinated just a few years previously, in 1978: “Gay brothers and sisters, you must come out!” The only path to full participation for gay people in society, the only path out of the shame and secrecy of my own adolescence, was through being visible, so that others—our colleagues and classmates, our children and neighbors, our parents and priests—would know we were there. Returning home in 1990 after South Africa’s liberation movements were unbanned and Nelson Mandela freed, I wrote publicly about my sexual orientation and co-edited a book on gay and lesbian life in South Africa. At the same time, I had a prominent career as a journalist, which was in no way damaged by being out of the closet.

Two decades later, in 2013, C and I were living in France when that country finally legalized same-sex marriage, upgrading the status from the Pacte civil de solidarité (Pacs), a form of civil union. On a Sunday in May, hundreds of thousands of people descended on Paris for the Manif Pour Tous, a rally against same-sex marriage and in favor of “the family,” supported by a Catholic Church trying to maintain relevance in a rapidly secularizing society. Many of the participants wore T-shirts showing a pictograph of four little stick figures: a mother, a father, and two children. Together with a South African friend, a white woman who with her wife had adopted two black children, I watched the crowds: their indignation seemed, to us, to come from confusion rather than anger, confusion at what had become of the certainties of their world. It seemed as if they were the new outsiders to a burgeoning social consensus: despite their numbers they were a minority of French people, according to the polls. Even in the United States, where “gay rights” had long been a casus belli for the culture wars, the annual Gallup poll showed that by 2016, 61 percent of Americans favored same-sex marriage.

Gay men or lesbians marrying and raising children; openly lesbian heads of state and openly gay multinational corporate executives; puberty blocking medication that helped children who planned to change their gender; presidential orders liberating transgender kids to use the toilets congruent with their gender identity. Such things were unthinkable when I had participated in New York Pride parades in the 1980s and helped organize the Gay and Lesbian Awareness Days at Yale.

Now, in my middle age, as the twenty-first century unfurled into its second decade, this change was happening in progressive enclaves of the world, in places such as the Bay Area, or Buenos Aires, or Amsterdam, or Cape Town. But the planet was spinning faster than ever before: due to the unprecedented movement of goods and capital and people and especially ideas and information—what we have come to call “globalization”—people all over the world were downloading these new ideas, often acquired online, and trying to apply them to their offline realities. Thus were they beginning to change the way they thought about themselves, their place in society, their options, and their rights. Even in places as far-flung as Blantyre, where Aunty held her chinkhoswe, age-old conventions governing sexuality and gender were being disrupted. There were new negotiations over what was private and what was public, what was illicit and what was acceptable by society.

From 2012 to 2018—the high-water years of this new global phenomenon—I traveled extensively, trying to understand how the world was changing, and why. I did not go everywhere. Rather, I chose places where I felt I could meet people who could best tell the story of how the “LGBT rights movement” was establishing a new global frontier in human rights discourse—in the way that the women’s rights movement, or the civil rights movement, or the anti-colonial movement, or the abolitionist movement, had done in previous eras. I wanted to understand how this new struggle was a consequence of these prior—and ongoing—ones, but also how different it was, too, in this era of digital revolution and information explosion, of consumerism and mass tourism, of mass migration and urbanization, of global human rights activism.

I tracked Aunty’s journey back from Cape Town—which advertises itself as “the gay capital of Africa”—to her remote home village in Thyolo. I followed a gay Ugandan refugee from Kampala to Nairobi in neighboring Kenya, and then on to resettlement in Canada. I hung out with trans and nonbinary kids from an LGBTQQA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Questioning, and Asexual) youth group in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and I followed them as they fanned out across the U.S. I spent time with a group of kothis—“women’s hearts in men’s bodies”—who ran a temple in a South Indian fishing village outside Pondicherry, and also with transgender software engineers working for multinational corporations in nearby Bangalore; with lesbian mothers in Mexico and transgender mothers in Russia; with queer Palestinians in trendy cafés in Tel Aviv and Ramallah and queer Egyptians at sidewalk cafés in downtown Cairo; at Pride marches in Tel Aviv and Delhi, London and Mexico City. And I followed the new international elite of activists and funders as they traveled the world in a never-ending circuit of meetings and conferences, forging the networks that advocated for this new global agenda.

I witnessed a troubling new global equation come into play: while same-sex marriage and gender transition were now celebrated in some parts of the world as signs of humanity in progress, laws were being strengthened to criminalize such actions in others. In 2013, the same year that the United Kingdom passed the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act, Nigeria promulgated its antithesis: the Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act. Even the parentheses were reactive. This was meant to provoke the former colonial oppressor, and the title was cynically preemptive, drawing a rhetorical line in the sand by promising to inoculate African society against future infection from the West. Nigeria’s was the harshest anti-homosexuality law in the world outside of Islamic Sharia: it prescribed mandatory sentences of fourteen years not just for sex but for any kind of “homosexual behaviour” or advocacy, including attending gatherings or associating with people thought to be homosexual.

Thus was a Pink Line drawn: between those places increasingly integrating queer people into their societies as full citizens, and those finding new ways to shut them out now that they had come into the open. On one side of this Pink Line were countries that had undergone social changes due to their own women’s rights and gay rights movements; these countries supported “LGBT Rights” as a logical application of the UN’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. On the other were those that condemned the idea as a violation of what they called their “traditional values” and “cultural sovereignty.” On both sides were Pink Line Warriors: either drawing a new line over the old frontiers between civilization and savagery, or claiming that they needed to stop the onset of the secular decadence of the West.

The latter meant, of course, the impossible task of trying to put up boundaries against the vectors of globalization itself. In the age of digital technology and social media, previously isolated people suddenly found themselves part of a global queer community, able to connect with others first in chat rooms and then on hookup sites or social media platforms; to download ideas about personal freedom and rights that encouraged them to become visible; and to claim space in society. But so, too, on the same platforms, could members of some faith groups forge networks—and access ideologies and strategies—far beyond their individual parishes or mosques. Religious identity, like sexual or gender identity, became globalized, and a clash between the two was inevitable.

There was a cultural bifurcation in some places. In Malaysia, conservative Islamism seemed to be gaining purchase: through the new adoption of Sharia laws that banned, among other things, “posing as a woman”; through raids on gay bars and the censorship of exhibitions; and even—in 2018—through an unprecedented sentencing of two women to public caning for lesbianism when they were found with a dildo in a car. But at the same time, younger and more urban Malaysians supported LGBT rights—as they did in many other places—as a way of branding themselves as part of the global village. When a prominent nationalist group called for a boycott of Starbucks in 2017 because the company supported gay rights, this made young urban coffee drinkers even more passionate about the “global space” the chain provided. A Malaysian acquaintance told me: “We go to Starbucks because it’s great coffee, but also because it’s part of the bigger world.” In India, middle-class professionals identified themselves as global citizens through their support of the decriminalization of homosexuality; in Mexico and Argentina, they did so through their support of same-sex marriage.

The Pink Line ran through TV studios and parliaments, through newsrooms and courtrooms, through bedrooms and bathrooms, through bodies themselves.

Mass migration had much to do with these shifts in consciousness: from the countryside to the city, and across national borders from one part of the world to another. People suddenly found themselves in worlds with mores utterly different from the ones in which they had been reared, beyond the reach of their clans or congregations. Perhaps fleeing persecution or struggling for economic survival, or perhaps taking advantage of the ability to travel or study that upward mobility brought, many experienced what is called “personal autonomy” for the first time: the power to make their own decisions about their lives. Then they carried such notions about sexual orientation or gender identity back home, to shake things up there. Traveling alongside them on the journey south or east, or from the city to the countryside, were Western aid workers and public health officials, activists, and tourists.

All this movement—across borders real and virtual, on land and in cyberspace—created a new sense of space and identity for people the world over. It also created a new set of challenges, as people attempted to toggle between the liberation they experienced online and the constraints of their offline lives, or between their freedom in the city and their commitments back home.

The Pink Line created new categories of people demanding rights—and also panicked resistance.

It created new horizons, as societies began to think differently about what it meant to make a family, to be male or female, to be human—and also new fears.

The Pink Line ran through TV studios and parliaments, through newsrooms and courtrooms, through bedrooms and bathrooms, through bodies themselves.

It cleaved Aunty’s life, and many others’ lives, too.

Writing about it seemed, to me, to be my debt to love.

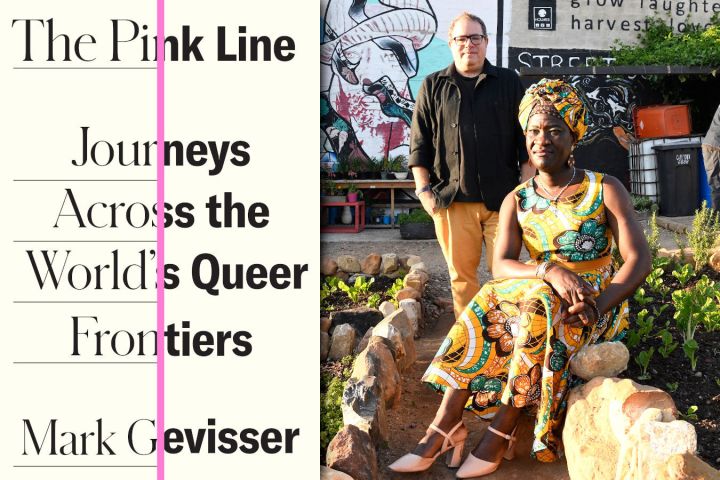

Mark Gevisser and Aunty with Chantel Samson, Zoliswa Mbana and Jesse Laitenen of StreetScapes Community Garden

Postscript: On Friday 24 July I delivered an inscribed copy of The Pink Line to Aunty at the Streetscapes Community Garden on Roeland Street in Cape Town, where she has recently been employed, through a private donor, as a gardener. Streetscapes Community Garden is a project of Khulisa, an NGO that provides work, housing, and support for chronically homeless individuals who have fallen through the cracks. Next to the Food Lovers Market, Streetscapes is open to the public, and is a place of light, hope and nourishment in these dark times. “I love it here,” Aunty told me. “I feel so respected.” In the six years of our acquaintance, I have never seen her so well.

When I met Aunty, she was working as a volunteer at Passop, a refugee organisation with an LGBTI focus. Passop continues to help Aunty, and is doing vital Covid-19 relief work for LGBTQ refugees in Cape Town. I am donating the equivalent of my royalties for all books sold in South Africa in 2020 to this and other pandemic relief initiatives that reach LGBTQ refugees. For more information about Passop: www.passop.co.za. For more information about Streetscapes: streetscapes.org.za.

This is an edited extract from The Pink Line by Mark Gevisser. DM/ ML

The Pink Line: The World’s Queer Frontiers by Mark Gevisser, author previously of Thabo Mbeki: The Dream Deferred and Lost and Found in Johannesburg, is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers (R280). Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

Photographs by Ellen Elmendorp / Composite: The Reading List

Become an Insider

Become an Insider