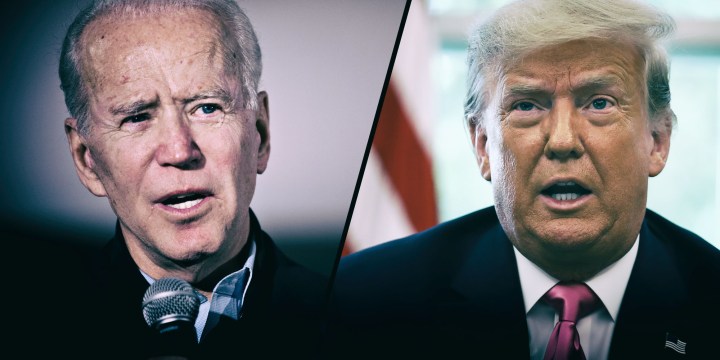

2020 US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS

It’s going to be one heckuva roller-coaster ride until the US polls in November

American presidential elections have sometimes been much more fraught with complications and intrigue than the anodyne version of some history books. The 2020 edition already looks like it may become a distillation of all the versions of chaos possibly drawn from the past, along with a couple of ‘wag the dog’ moments thrown in for good measure.

One certain thing about elections is that eventually, they must come to an end. Mercifully, there will be an end to it, people are starting to say of this current presidential election in the US. (That is, of course, unless it comes to the moment where the presumed loser starts mewling about it having been rigged, a fraud, a hoax, fixed and a travesty — or, in the usual more spartan prose of international electoral monitoring parlance, neither free nor fair.)

In truth, Donald Trump has already laid down several increasingly acrid, system-corrupting markers about his not automatically accepting the results of the upcoming 2020 election if he judges things to have been a hoax — and therefore that acquiescence to his loss might not be automatically forthcoming from him — or his angry, riled-up supporters. Trouble in River City, for sure.

Denying the fundamental legitimacy of the results of an entire election would seem to be unprecedented in the history of American presidential elections. The nation is definitively not one of those banana republics, people have been eager to protest about this question; it is not like one of those places where comic opera armies depose elected presidents at the drop of a plumed helmet. Such coups, of course, sometimes also have a way of turning into brutal authoritarian dictatorships, so it isn’t always so comic. Something to think on.

This writer has largely agreed over the years with the view that says the US is exceptional in always having had a regular cycle of elections and the rather frequent replacement of its chief executive, once the will of the people has spoken. Nevertheless, it is also true there have been circumstances where the results were not immediately accepted (or even known), or where they were subject to much partisan rancour — even to the point of tearing the nation in half after a contested election.

The first such conflicted election came in the country’s third vote where a quirk in the original electoral clauses in the constitution produced a result no one had really anticipated. The first two elections had been won by George Washington as almost unanimous choices, with John Adams as his deputy. The original electoral college clauses establishing the indirect voting for president had been to draw on Plato’s ideal of wise elders actually picking the best national leader, based on their years of experience. The founders were exceedingly reluctant to turn over such a choice to the rabble, following their study of all the failed republics from history. Partisan politics and leadership slates were still a decade or so into the future.

But in the 1796 election, Vice President John Adams became president and the secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, became his vice president. This result was unexpected because the two men came from the two very different, but only newly established political parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.

Adams was an advocate of an increasingly robust, centralised federal government, while Jefferson had been an advocate of a loose national state with most power devolved to the states and on to individual citizens. True, they had worked together during the independence struggle and in Washington’s presidency, but, by the 1790s, they had come to represent deeply divergent views, something that led to a very strained, contentious four years during the Adams presidency.

Then, four years later, the two men squared off against each other a second time. With Jefferson and his vice presidential running mate, Aaron Burr both receiving the same number of electoral votes, the final disposition of that election was up to the House of Representatives which finally confirmed Jefferson as the country’s president, per those now-confusing constitutional provisions. This wrangling eventually led to a constitutional amendment in which presidential and vice-presidential candidates were regarded as a unified electoral choice, rather than as separate, independent candidates, ready to rumble, with the opposition or each other.

Out of this result, Burr obviously was not an entirely happy camper as he had now lost his chance for glory. He went on to kill his old law partner, Alexander Hamilton in a duel (after Hamilton had established the foundations for the national government’s financial structures), and Burr eventually drifted on to various shady speculations and adventures to create his own empire in the newly acquired lands of the West — or even in Spanish Mexico. In all this, remember, Burr had been just one vote away in the electoral college from having become president back in 1800.

The next major crisis erupted in 1860. The incipient split of the country over the expansion or even continuance of slavery in the southern half of the country meant there were four major candidates for the presidency, effectively running parallel elections in the north and the south.

Abraham Lincoln, as the new Republican Party’s candidate, faced Stephen Douglas in northern states, while in the southern half of the country, a second Democratic Party candidate, John Breckenridge, faced John Bell, running on behalf of the remnants of the Whig Party, now renamed the Constitutional Union Party, hopeful of regaining power with a platform that resolutely refused to deal with the slavery question. With Lincoln’s victory of a majority of northern (and thus effectively of the national), electoral votes, he became president-elect and eleven southern states eventually chose rebellion rather than accept the 1860 election.

Eleven years after the end of the Civil War, a hotly contested 1876 election was ultimately resolved in an entirely unprecedented fashion. Republican Rutherford B Hayes faced Democratic Party candidate, Samuel Tilden. Tilden had won an absolute majority of the popular vote, but as a result of charges of widespread voting fraud and duplicate, competing vote certifications from several states, a special bipartisan committee was appointed to work through the charges and determine the winning candidate in the contested state results.

This commission ultimately awarded the electoral votes from Oregon to the Republicans by an 8-7 vote. This was part of an informal agreement by several Democratic commissioners to support the Republican candidate in a quid pro quo promise he would order the removal of all remaining federal troops still occupying the southern states, once Hayes became president.

Democrats obviously wanted the occupation to end in order to regain control of the governments of the states formerly in rebellion. (Along with that agreement, there was the implicit promise that the Reconstruction era would end, thereby allowing ever-tighter restrictions on the African-American vote and any holding of public offices by black Americans in the south. Say, “Hello, Jim Crow”, as this system of racial segregation was usually nicknamed.)

The most recent electoral squabble in American presidential politics — so far, at least — took place in 2000, when Vice President Al Gore confronted the Republican Texas Governor, George W Bush. Ultimately, that election narrowed down to a dispute over who had won the popular vote in Florida. With Florida’s electoral weight on their side in that closely divided election, that would determine who would become president.

With the ultimate decision hanging on the validity of fewer than 2,000 contested ballots and increasingly arcane disputes over the hanging or dimpled chads of the Hollerith computer cards recording individual votes, after weeks of recounts and legal wrangling, the Supreme Court ultimately decided in a 5-4 vote that Bush had won the Florida electoral vote. Thereupon, the now-defeated Gore issued a gracious — especially given the highly charged circumstances — concession speech and the republic was saved, even if the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq almost inevitably flowed from that.

But 2020’s election, at least as it stands now, almost certainly will be something unique. And not necessarily in a good way. In the first place, the traditional nominating conventions are being shrink-wrapped down to a kind of virtual production, courtesy of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the party nominating conventions generally no longer function as places where competing intra-party factions and candidates duke it out for who will become their party’s nominee, they have become highly visible places for fights over the party platforms and, most especially, via television and online streaming, one of the best ways to communicate to a nation — unmediated by others — the goals and soul of a candidate. Their acceptance speeches become launching pads for speeches and campaign media that will follow — setting out the core (and hopefully winning), themes of a campaign.

But this year is different. There will be no big crowds at rallies and there will be no big speeches at those (non-existent) rallies. That helps explain the way Trump has been giving some hyper-partisan remarks from inside the White House grounds, as well as a growing number of big-picture presentations by Joe Biden as he begins to roll out a competing economic message.

For Biden, his key campaign project is to give the president lots of space and lots of rope to hang himself — repeatedly — with his intemperate or incoherent remarks — and wild accusations. This is on the assumption (borne from at least some survey data), that the nation’s population increasingly craves calmness, normality and a chance to return to a more predictable universe, rather than being riveted to the television to learn what new horror is being visited upon them every morning by the chief executive.

Above all, Biden hopes to offer the public a sense that his national leadership will feel the public’s hurt and confusion from the ongoing impact of Covid-19, the economic pain felt by millions of newly out of work or furloughed employees, and the sense of anger and anguish — as well as leading to public demonstrations nationwide — that stem from racial circumstances now risen to the surface due to the highly visible police killings of younger African Americans, such as George Floyd.

Biden’s bet is that focusing on economic issues through a proposed infrastructure rebuilding programme and a more effective, inclusive social safety net will draw attention to his empathetic qualities (and thus his electoral attractiveness).

Trump, by contrast, had his one great trump card, a robust economy and self-levitating stock market, largely removed from his hand by the pandemic and the ensuing economic collapse. (The polling, surprisingly, still seems to reflect feelings among voters that Trump has reasonably good instincts on economic issues. One wonders whether that will change if unemployment stays high through the early autumn, however.)

In an effort to get his groove back, Trump has fallen back on — doubling down on — a deeply divisive politics, the wedge issues; the approaches he believes got him to the White House in the first place. (Elections are won by inspiring “your people” to vote and discouraging “their people” from doing so.)

Now that the economic argument remains largely moot for him, preeminent for the president’s chances, now, is to be the “law and order” president 2020, presumably reasoning that it worked well for Richard Nixon back in 1968 — what with urban riots, anti-Vietnam War protests on campuses and beyond, and perceptions of a generally high level of crime.

A sufficient number of the electorate largely tuned out from other messages and, except for some southern voters, Nixon managed a tight victory over the hapless vice president, Hubert Humphrey. For Trump, he seems to have theorised that the demonstrations, and incidents of violence and looting following Floyd’s death have given him the opportunity to be a 21st-century law and order president, overwhelming all the other issues afflicting the nation. This is, as New York Times columnist Tom Friedman has observed, a “wag the dog” strategy. As Friedman wrote: “Some presidents, when they get into trouble before an election, try to ‘wag the dog’ by starting a war abroad. Donald Trump seems ready to wag the dog by starting a war at home. Be afraid — he just might get his wish.”

How did we get here? Well, when historians summarise the Trump team’s approach to dealing with Covid-19, it will take only a few paragraphs:

“They talked as if they were locking down like China. They acted as if they were going for herd immunity like Sweden. They prepared for neither. And they claimed to be superior to both. In the end, they got the worst of all worlds — uncontrolled viral spread and an unemployment catastrophe.

“And then the story turned really dark.

“As the virus spread, and businesses had to shut down again and schools and universities were paralysed as to whether to open or stay closed in the fall, Trump’s poll numbers nose-dived. Joe Biden opened up a 15-point lead in a national head-to-head survey.

“So, in a desperate effort to salvage his campaign, Trump turned to the Middle East Dictator’s Official Handbook and found just what he was looking for, the chapter titled, ‘What to Do When Your People Turn Against You?’”

In essence, this strategy is to create a war and the people will follow, or at least enough of them will do so to survive the voting on 3 November 2020. The New York Times reported on 23 July 2020:

“President Trump announced yesterday that he would send hundreds more federal agents to Chicago and other American cities, significantly expanding the scope of a program that has been criticised by Democrats as borderline authoritarian.

“‘We will never defund the police,’ Trump said, hammering at a message that has become central to his reelection campaign. ‘We will hire more great police. We want to make law enforcement stronger, not weaker. What cities are doing is absolute insanity.’

“Federal officers under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security have been clashing with protesters in Portland, Ore., since last week, and yesterday the state’s attorney general argued in court for a restraining order to expel the federal agents from the city. Trump and William Barr, the US attorney general, told reporters that the administration would be sending officers to Chicago not to combat protesters but to help fight a recent rise in violent crime there. ‘We’re going to continue to confront mob violence,’ Barr said. ‘But, the operations we are discussing today are very different — they are classic crime fighting.’ The administration has also ordered agents into Kansas City, Mo., with a similar mission.

“This seems to stretch the administration’s previously stated justifications for deploying federal officers into cities. Those rested on the executive order that Trump signed last month to protect monuments and statues, and on the DHS’s [Dept of Homeland Security] original charter, which says that troops can be used to protect public property.”

Not surprisingly, observers in Portland have noted that the protesters had been declining in numbers until those federal whatevertheyares arrived, thereby triggering more protesters, and even middle-aged groups of “moms” and “dads” who arrived downtown to try to ward off the federals who have been dressed in the 21st-century camo gear equivalent of Star Wars-style imperial stormtroopers, and without name tags, rank insignia, or any clear idea by the public regarding under whose command, or rules of engagement they were operating.

Concurrently, the Trump administration, seemingly desperate to show strength in international affairs as well, come what may (and to distract even further from the unchecked pandemic and the economic crisis), has ratcheted up a growing conflict with China that originally emanated from trade balance disputes and derived further strength from a dispute over how Covid-19 spread globally and why.

Now, the Trump administration has suddenly ordered the immediate closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston (with the presumption they had been using it to snoop on America’s energy sector, along with continuing allegations of Chinese spying more generally, and finger-pointing at the Chinese about election interference). Soon enough, of course, the Chinese will be compelled to carry out a reciprocal response. Old China hands in the US are now betting about whether the Chinese will want to close the US consulate in Shanghai, Wuhan, or even Hong Kong. Can you wag two dogs at the same time?

Taken together, here at the tail end of July 2020, we have a Trump administration struggling to show the need to bring about some steel teeth-style law and order in order to crush civil unrest (but only in cities with Democratic Party mayors), as the prime raison d’être for its reelection. If that were still not sufficient, the president is now also arguing the country needs him for four more years to see it through on China (Shush: Just forget about all those instances of Russian election interference in 2016, or the strong possibility of there being more of this to come in 2020 – presumably on behalf of Trump).

And if this still doesn’t work, in combination, they will just continue to ratchet up this faux-commotion about a hoax, rigged, fake, fraud-infested election in which the Democrats will rely upon millions of fraudulent mail-in ballots printed in China, unless it looks like a blow-out by the Biden ticket.

Their strategy would seem to be to prepare a distillation of all the electoral dramas from the 1796, 1800, 1860, and 2000 elections combined and use them to stir the 2020 pot. Moreover, if it takes days or even weeks to get all the tabulations right, unlike the recent versions of election day reporting in which results were generally available by midnight, days of delay will be all the time needed for Trump and his hoplites to increase the whining intensity of his allegations about this fixed election, putting the country into an even more agitated state than it already is.

For the more excitable, or imaginative, or perhaps those who are devotees of pot-boiling political thrillers, that is precisely how the incumbent president wants things. This will allow him to attempt to stay in office under the fig leaf of some kind of national emergency martial law status.

But, as calmer heads have reminded, assuming the votes are fully counted, the constitution is very clear about when a president leaves office — on 20 January, at noon. No ifs, ands or buts. But if there is no final answer as to who won the election — well, then, the (Democratic) Speaker of the House of Representatives is sworn in to serve.

It takes 270 of 538 electoral votes (equaling the number of total senators, representatives and three for Washington, DC apportioned by population to the states) to win. If the two candidates split evenly and there are one or two disputed votes, then it is President Nancy Pelosi. That has an interesting ring to it. Is that what Republicans really want to see happen? Maybe a few senior Republican senators should have a quiet chat soon with Trump about his rhetoric — and his actions. The next several months are going to be one heckuva roller-coaster ride until 3 November 2020. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider