SPORT

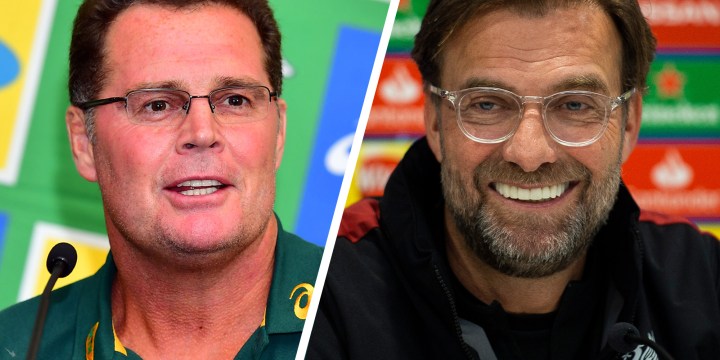

Rassie Erasmus and Jurgen Klopp show that great success stems from visionary leaders

Having good leaders does not automatically lead to sporting success. Having great leaders with the rare ability to connect and inspire players, owners and fans, is what differentiates the good from the great. Jurgen Klopp and Rassie Erasmus share these traits, and it’s why they have brought success to their respective teams.

Jurgen Klopp and Rassie Erasmus have many parallels and similarities. Both were professional players in their respective sports of football and rugby, both became head coaches at a young age, and both led unfashionable teams to titles.

Erasmus’ crowning achievement was guiding the Springboks to Rugby World Cup 2019 glory 20 months after they suffered record defeats. For Klopp, it was turning Liverpool from also-rans into 2020 Premier League champions, which ended a 30-year title drought for the storied Merseyside club.

Two men from opposite ends of the world have far more in common than they probably realise.

Klopp started his coaching career at the small German club called Mainz where he had been a modest player. They won promotion to the Bundesliga (Germany’s top division) after three years under Klopp. Despite the smallest budget in the league, Mainz managed two mid-table finishes in the next two years before relegation. Klopp stuck with the club and was eventually lured to the bigger, but under-achieving Borussia Dortmund.

In his third year there, Dortmund won the Bundesliga with the youngest side ever. They repeated the success the following season and also made the Champions League final a year later. Klopp joined Liverpool in late 2015 and has so far guided them to the 2019 Champions League crown and the 2020 Premier League title, as well as becoming World Club Champions. Klopp’s project at Liverpool took three-and-a-half years to deliver silverware.

Erasmus’ journey was similar, although, unlike Klopp, he was a successful player – a Springbok and winner of the Tri-Nations among other titles. Like Klopp, he was in his early 30s when he started coaching the unfashionable Cheetahs in 2004. In 2005 Erasmus’ youthful team won the Currie Cup for the first time in 29 years. They shared the title the following year before Erasmus assisted the Boks in 2007 – the year they won the World Cup.

He became director of rugby at Western Province where he laid the groundwork for a successful period with head coach Allister Coetzee pulling the strings on the field. In 2012, Erasmus moved to the SA Rugby Union as High Performance Manager of rugby and immediately played a role in the Junior Springboks winning the World Championships.

After a short stint with Munster in Ireland between 2016 and 2018, which saw his team topping the Pro12 standings and Erasmus winning the coach of the year award, he returned to coach the Boks. The rest is history.

Coaching philosophies and game plans

Those are the broad coaching successes of the two men, but their achievements are built on values, systems and leadership styles that are inclusive, honest and focused.

Erasmus and Klopp both have very specific game plan ideas – philosophies if you like – for their respective sports.

In rugby Erasmus wanted the Boks to be able to play at a high intensity, do the big things such as scrum, lineout and defend well first, before adding layers. Once the basics were superb and second nature, playing with an intensity that would hurt opponents was the next step up.

Erasmus’ Springbok game plan, which was based heavily on territory and set pieces, required athletes to be able to perform in certain ways. The wings had to be able to do repeat sprinting sessions, chasing kicks, while the forwards not only needed power, but agility to defend for long periods. Making tackles, getting back on their feet quickly and repeating the process over 80 minutes required less bulk but more aerobic capacity.

The players enjoyed hours of “gorilla ball”, a game played on a volleyball court using a medicine ball, which combined agility and strength.

On the field, sessions surpassed the match-day intensity, but they were always controlled. Everyone was monitored for signs of fatigue and stress and managed according to the data.

Erasmus told his players not to worry about making mistakes. He wanted them to get into more battles within the game. He’d rather the players went into 85 individual battles in a match and lost 10, than go into 40 and only lose two. Collective intensity and desire leads to consistency and are better than individual moments of brilliance in the long run. It’s not to say he doesn’t value individual brilliance – Cheslin Kolbe is a prime example – but it cannot come at the expense of the collective effort.

Klopp has a similar philosophy by using data to recruit the type of players that suited his ideal vision of how football should look. It’s fast, it’s about limiting the opponent’s space and time and about turning defence into attack in the blink of an eye. It has been called Gegenpressing in German, where the team, after losing possession, immediately attempts to win back possession, rather than falling back into a defensive formation.

Klopp’s teams are usually considered the fittest because of the intensity they have to operate at to successfully play this way. In his first two years at Liverpool in particular, several players who did not fit the style were worked out of the club, while many others suffered muscle injuries as they adapted to the intense training regimes.

Mentality and team culture

But for both coaches, these ideas and methods can only be underpinned by honesty, which comes from trust and a positive team culture. Erasmus was ‘open’ to the point of incredulity with the media. He didn’t play selection games and told it like it was – he even told the opposition what his team would do. It showed a team that was comfortable with itself.

Klopp is similar. Liverpool don’t change their formation because of the threat posed by the opposition. They play three strikers, three midfielders and four defenders with the left and right backs playing more like wings. It never changes. Opponents know what’s coming but they find it difficult to stop.

It works because the players are fully invested, completely informed and part of the process. It’s inclusive and collective. Klopp surrounds himself with experts and isn’t afraid to delegate. Erasmus is the same.

To make that approach work, it has to be directed by a culture that is non-toxic while manically driven towards success. It’s a difficult balance, which is where rare leaders such as Klopp and Erasmus excel. They have a way of driving players and colleagues to be the best without letting the environment become poisonous and infected.

“He (Klopp) sees through situations and processes,” Liverpool assistant coach Pep Lijnders told The Athletic. “There is a saying that people don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.

“And I think everyone who works with Jurgen has the feeling he really cares about you and your development. There is no ego, he purely searches for the right thing to do.”

Ego, or lack of it, is the key

Shortly after he became head coach of the Springboks, Erasmus told his team that there was no place for egos and entitlement in his set-up. He admitted that as a successful player himself, he became an ‘asshole’ because he let his over-inflated ego allow him to feel entitled. It was destructive.

In a powerful video of an early Bok team meeting Erasmus posted on social media, he demonstrated that ego and entitlement were a natural process that players would go through, and that was okay. As long as it was acknowledged and confronted.

“The journey of a Springbok player will always follow the same path,” Erasmus told his players. “You’re desperate to become a Bok and you sacrifice a lot to make it happen. Once you’re selected you still make those sacrifices because you are honoured to be in the team.

“Then what follows is that you get satisfaction and rewards. You get a better contract and sponsorships. You become a brand and have a following, yet you still sacrifice because you want all of this and you’re still desperate to be there. You are still willing to fucking sacrifice everything to be in the set-up.

“Unfortunately, the next step from here is that you become entitled because of the rewards and satisfaction. It’s a normal cycle of every Springbok player. I know very few successful players who haven’t gone through this. Reaching the level of becoming entitled is not a bad thing in itself – what matters is how long you stay there. Some guys get stuck at entitlement and as a result they only play a handful of games.

“You have to take ownership of these steps and keep checking yourself. I went through two years when I was a player stuck at the level of entitlement and no one told me that I was being an absolute ‘dick’. I was player of the year, I had a good contract, was earning excellent money and part of a Bok team that won 17 Tests in a row.

“But Harry Viljoen, a successful businessman who became Bok coach, dropped me. I couldn’t understand why this guy had dropped me. And it was then that my buddies told me it was because I was an asshole. They told me I was entitled and actually a virus in the team because I was such a bad team player. You have to take ownership of this personally, but you also have to take ownership for the team. If you don’t have the balls to tell your teammates they are being entitled, then you are also not taking ownership.

“This is a big part of our team selection. You could be the most brilliant rugby player, but if you are an entitled person, you’re not going to make it.”

That, in a nutshell, defines the Klopp and Erasmus way. It is successful because egos and entitlement are banned. It works and they have the trophies to prove it. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider