BOOK EXCERPT

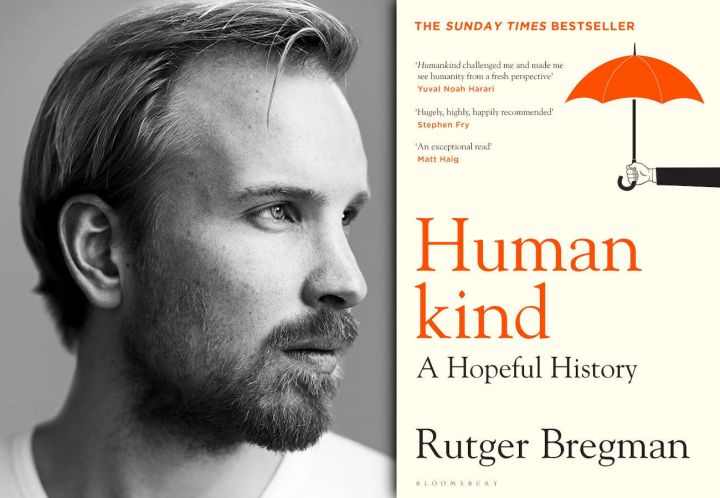

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind makes the case for seeing the good in people

“Taxes, taxes, taxes. All the rest is bullshit, in my opinion,” said Rutger Bregman at Davos in 2019. It was a breakout moment for the journalist and historian, who subsequently wrote a bestseller and appeared on Trevor Noah’s The Daily Show.

His long-awaited second book, billed as ‘Sapiens for the 20th Century’, takes on a belief that unites the left and right, psychologists and philosophers, writers and historians: the tacit assumption in the West that humans are bad.

Humankind: A new history of human nature makes the case for a fresh argument: that it is realistic, as well as revolutionary, to assume people are good.

Here is an excerpt from Humankind, exclusive to Maverick Life.

***

On the eve of the Second World War, the British Army Command found itself facing an existential threat. London was in grave danger. The city, according to a certain Winston Churchill, formed ‘the greatest target in the world, a kind of tremendous fat cow, a valuable fat cow tied up to attract the beasts of prey’.

The beast of prey was, of course, Adolf Hitler and his war machine. If the British population broke under the terror of his bombers, it would spell the end of the nation. ‘Traffic will cease, the homeless will shriek for help, the city will be in pandemonium,’ feared one British general. Millions of civilians would succumb to the strain, and the army wouldn’t even get around to fighting because it would have its hands full with the hysterical masses. Churchill predicted that at least three to four million Londoners would flee the city.

Anyone wanting to read up on all the evils to be unleashed needed only one book: Psychologie des foules – ‘The Psychology of the Masses’ – by one of the most influential scholars of his day, the Frenchman Gustave Le Bon. Hitler read the book cover to cover. So did Mussolini, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt.

Le Bon’s book gives a play by play of how people respond to crisis. Almost instantaneously, he writes, ‘man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilization’. Panic and violence erupt, and we humans reveal our true nature.

***

On 19 October 1939, Hitler briefed his generals on the German plan of attack. ‘The ruthless employment of the Luftwaffe against the heart of the British will-to-resist,’ he said, ‘can and will follow at the given moment.’

In Britain, everyone felt the clock ticking. A last-ditch plan to dig a network of underground shelters in London was considered, but ultimately scrapped over concerns that the populace, paralysed by fear, would never re-emerge. At the last moment, a few psychiatric field hospitals were thrown up outside the city to tend to the first wave of victims.

And then it began.

On 7 September 1940, 348 German bomber planes crossed the Channel. The fine weather had drawn many Londoners outdoors, so when the sirens sounded at 4:43 p.m. all eyes went to the sky.

That September day would go down in history as Black Saturday, and what followed as ‘the Blitz’. Over the next nine months, more than 80,000 bombs would be dropped on London alone. Entire neighbourhoods were wiped out. A million buildings in the capital were damaged or destroyed, and more than 40,000 people in the UK lost their lives.

So how did the British react? What happened when the country was bombed for months on end? Did people get hysterical? Did they behave like brutes?

***

Let me start with the eyewitness account of a Canadian psychiatrist.

In October 1940, Dr John MacCurdy drove through southeast London to visit a poor neighbourhood that had been particularly hard hit. All that remained was a patchwork of craters and crumbling buildings. If there was one place sure to be in the grip of pandemonium, this was it.

So what did the doctor find, moments after an air raid alarm? ‘Small boys continued to play all over the pavements, shoppers went on haggling, a policeman directed traffic in majestic boredom and the bicyclists defied death and the traffic laws. No one, so far as I could see, even looked into the sky.’

In fact, if there’s one thing that all accounts of the Blitz have in common it’s their description of the strange serenity that settled over London in those months. An American journalist interviewing a British couple in their kitchen noted how they sipped tea even as the windows rattled in their frames. Weren’t they afraid?, the journalist wanted to know. ‘Oh no,’ was the answer. ‘If we were, what good would it do us?’

Evidently, Hitler had forgotten to account for one thing: the quintessential British character. The stiff upper lip. The wry humour, as expressed by shop owners who posted signs in front of their wrecked premises announcing: MORE OPEN THAN USUAL. Or the pub proprietor who in the midst of devastation advertised:

OUR WINDOWS ARE GONE, BUT OUR SPIRITS ARE EXCELLENT. COME IN AND TRY THEM.

The British endured the German air raids much as they would a delayed train. Irritating, to be sure, but tolerable on the whole. Train services, as it happens, also continued during the Blitz, and Hitler’s tactics scarcely left a dent in the domestic economy. More detrimental to the British war machine was Easter Monday in April 1941, when everybody had the day off.

Within weeks after the Germans launched their bombing campaign, updates were being reported much like the weather: ‘Very blitzy tonight.’ According to an American observer, ‘the English get bored so much more quickly than they get anything else, and nobody is taking cover much any longer’.

And the mental devastation, then? What about the millions of traumatised victims the experts had warned about? Oddly enough, they were nowhere to be found. To be sure,there was sadness and fury; there was terrible grief at the loved ones lost. But the psychiatric wards remained empty. Not only that, public mental health actually improved. Alcoholism tailed off. There were fewer suicides than in peacetime. After the war ended, many British would yearn for the days of the Blitz, when everybody helped each other out and no one cared about your politics, or whether you were rich or poor.

‘British society became in many ways strengthened by the Blitz,’ a British historian later wrote. ‘The effect on Hitler was disillusioning.’ DM/ML

Humankind: A New History of Human Nature by Rutger Bregman is translated from the Dutch by Elizabeth Manton and Erica Moore (Bloomsbury, R320). Available in South Africa from 1 July at The Book Lounge, Love Books, Exclusive Books, Takealot and other retailers. Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts – daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider