I last attended the National Arts Festival in what was then called Grahamstown in the late-1990s. It was the year I first owned a cellphone, a device I treated with some contempt.

Whereas today no live theatrical performance can start before a voice reminds you to switch those damned things off, back then when mine rang in a half-empty makeshift theatre midway through an intimate two-hander, I didn’t even register what the strange, insistent ringing was. Shamefully, I let it continue while the poor actors grappled with their dialogue.

I eventually clicked only when everyone – audience, theatre technicians, and both cast members – stopped to stare, blatantly, in my direction. And, in the deathly silence, I blushed while realising that I was the source of the disturbance. In that moment, everyone briefly fell about in stitches – we were shocked at the absurdity of it. Surely such intrusions were a passing plague?

Little did we know that the world and its reality had changed and we had entered a future in which we would all be carrying little interruption devices around with us.

These were technological marvels possessing the power to stop artist-shamans mid-trance, and to distract those of us in the audience from engaging with the stories being told around the fire. Metaphorically speaking, of course.

Back then, none of us realised that eventually those devices would be “smart” and capable of broadcasting entire television channels, movies, and – now, thanks to a different sort of plague – an entire arts festival.

It is a strange and ironic turn of events, but one – like the ubiquity of cellphones – we might as well get used to.

***

At some point shortly after that last visit to Makhanda, my life altered course and I de-prioritised my pilgrimages to its annual festival. I’ve spent over two decades privately reminiscing about it and making unfulfilled promises of returning to relive the magic of those 11 heady days.

Which is why the transition of this year’s National Arts Festival into one that’s entirely virtual is both a shock and a blessing.

To those of us who’ve grown used to cooking up excuses not to attend it’s a chance to rekindle an old romance. And those of us who’ve never bothered or been able to be there, it offers the chance to attend without the twin sensations of risk and responsibility: You can go to Makhanda without much planning and witness the shamans telling their stories without leaving home. You get to experience the virtual National Arts Festival (vNAF) at a greatly reduced cost, and “attend” its shows and experiences in the sweatpants-and-no-underwear privacy that comes with being an utterly anonymous, physically distanced observer.

Then again, witnessing a videoed version of a stage play on a small screen can be less-than-thrilling. There is something to be said for sharing the same air, physical space and emotional blood and sweat with live performers. Of knowing that a cough or laugh or clap or snore – and a blasted ringtone – can infiltrate the production and alter its meaning, or change its intensity.

During the early days of lockdown, I was fascinated by the idea of watching all sorts of filmed and streamed theatre productions on my laptop, but it really wasn’t the same. For all the hassle of driving there and enduring the changeable weather, Shakespeare is simply better under the stars at Maynardville. Perhaps it’s the sense of occasion, or simply the wind through the trees.

Part of the problem is that our private spaces include multiple distractions and domestic disturbances. Anyone streaming TV shows knows about the ease of pausing to pee or raid the fridge.

Which is why the people who planned this year’s festival have cunningly curated a programme that addresses the nature of the medium via which it’s happening.

What they’ve developed isn’t simply a stay-at-home simulacrum of live theatre. Instead, many of the productions grapple explicitly with the tension that exists between the live and digital arts. It is a festival that interrogates the present-moment evolution of human experience in response to virtual and digital technologies.

Together with certain core festival elements – the jazz programme, music concerts, art exhibitions – they’ve envisioned a kind “digital playground” in which artists will be investigating the boundaries of our current understanding of what “art” is. Part of that exploration is an examination of the nature of theatre, the role of audience, and even the ubiquity of humans as storytellers.

Leading this charge into the virtual unknown is the third instalment of Creativate, the festival’s dedicated digital arts stream, which provides “a glimpse into the future of the arts”. Which is a phrase which might give cause to shudder if you’re imagining dramas enacted by robots or modern dance choreographed by AI.

And, in fact, you wouldn’t be completely wrong.

In Human Study #1, From a Distance, artist Patrick Tresset has his autonomous robots in Belgium observe you (presumably via the camera above your screen) and then – once you’ve watched them “think” about what they’re seeing – you get to watch them sketch your portrait.

And in something called Futurabilities, a conversation will unfold “as a programmed Bot reads to other chatbots, who in turn answer and learn from the conversation”. The point, for the humans watching, is to try and convey some sense of how data systems learn new things about us and how they learn from us.

Then there’s In Limbo, a sci-fi documentary that imagines what it might be like if the internet could dream of itself. To quote a human, “Wait! What?”

And, in case you’ve grown excessively fond of Zoom over the last few months (Stockholm Syndrome, anyone?), you might get a kick out of Creativate’s digital art workshops, which include sessions on animation (digital of course) and a series of “extended reality” workshops covering the growing fields of augmented reality, virtual reality and holograms.

There’s a tutorial in creating deepfake avatars for Zoom and Facebook Live. And there’s a webinar that – over 90 minutes – talks artists and theatre practitioners through the process of “digital transformation”.

Avatars in Zoom is a hands-on Creativate tutorial by Gruss Eyal

Fear not, it’s not all VR headsets and our imminent transcendence into a series of 1s and 0s. There are real actors doing their thing, too. The main programme includes, for example, Attempt on Dying, a live interactive theatrical work by Swiss theatre director Boris Nitikin. Performed on Zoom, it offers the opportunity for audience members to actively participate despite their physical remoteness.

Also experimenting with the audience’s role in the mechanics of the medium is Meta / M O R P H, an online collaboration between a choreographer, projection artist, filmmaker and VR artist. Their aim is to produce a series of interactive dance films that will be the result of viewer inputs – a kind of virtual and collaborative “choose your own adventure”.

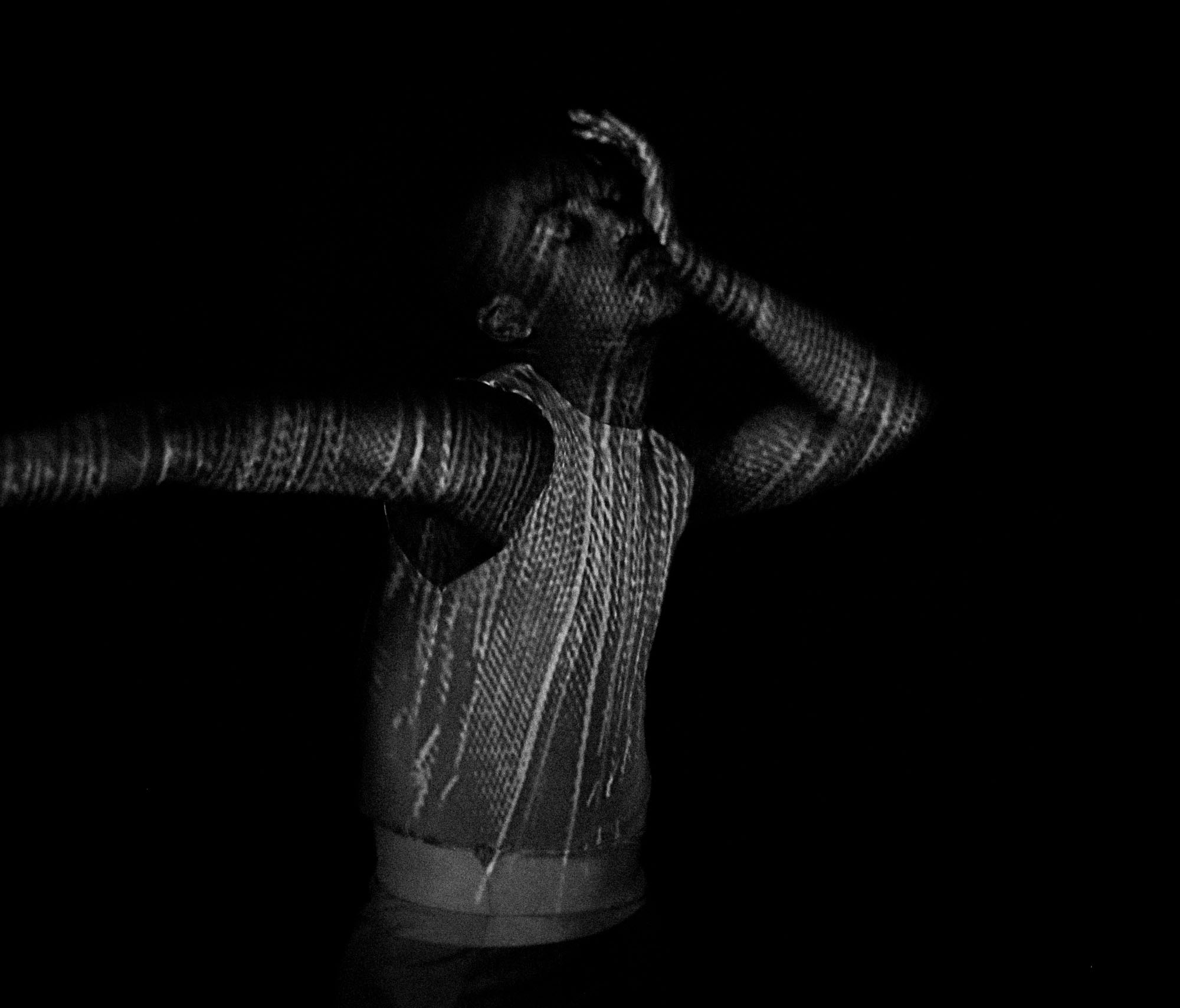

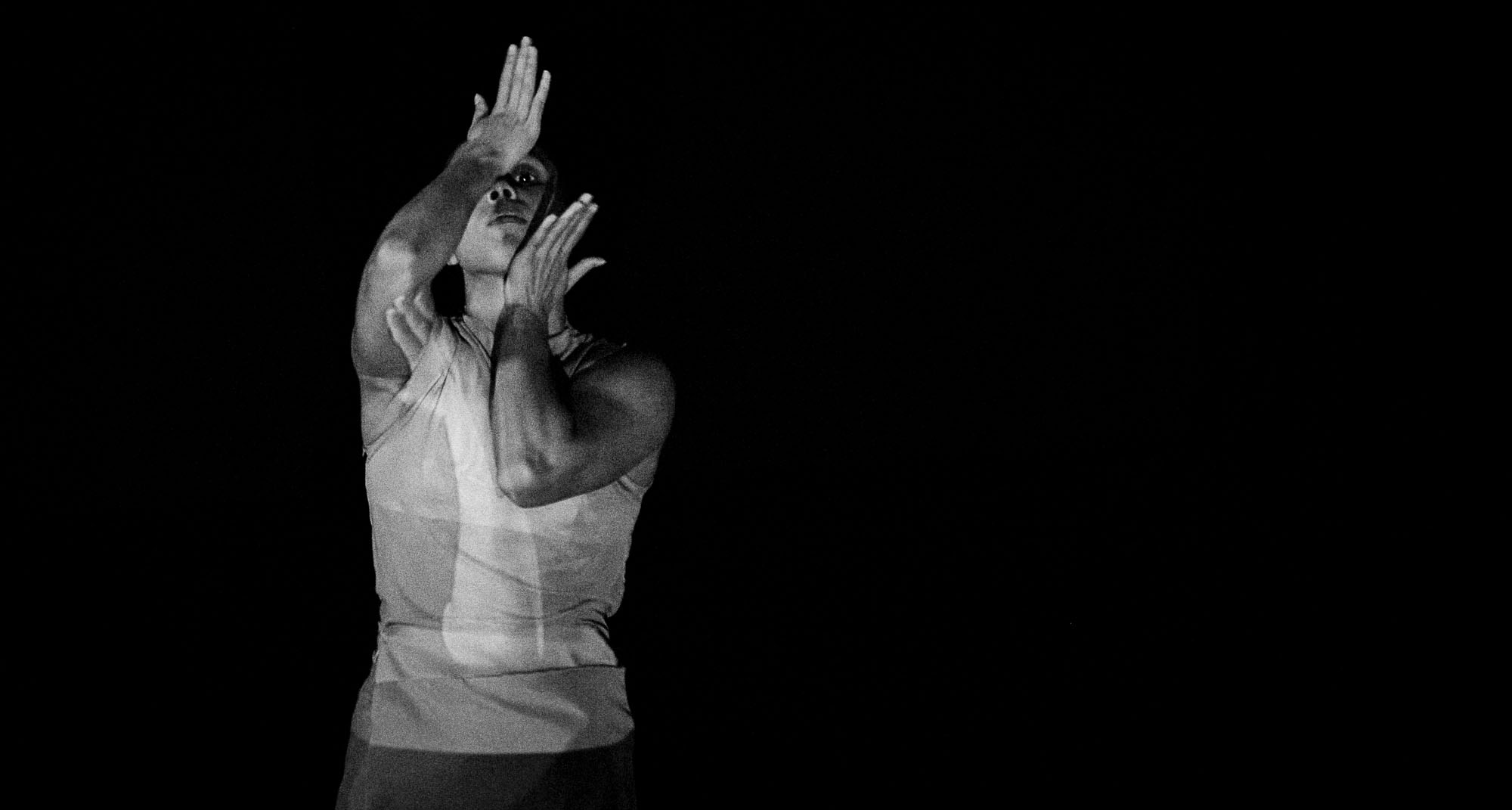

‘META : m o r p h’ – photo by Oscar O’Ryan

‘META : m o r p h’ – photo by Oscar O’Ryan

Then there’s Jigsaw, a five-way artistic collaboration that uses lockdown’s physical separation to its advantage. Artists in three cities tell a story within a two-dimensional space (the screen), but by using a multiplicity of mediums – performance, music, animation, video effects and live editing – they create a filmic experience (via Zoom) that is anything but two-dimensional.

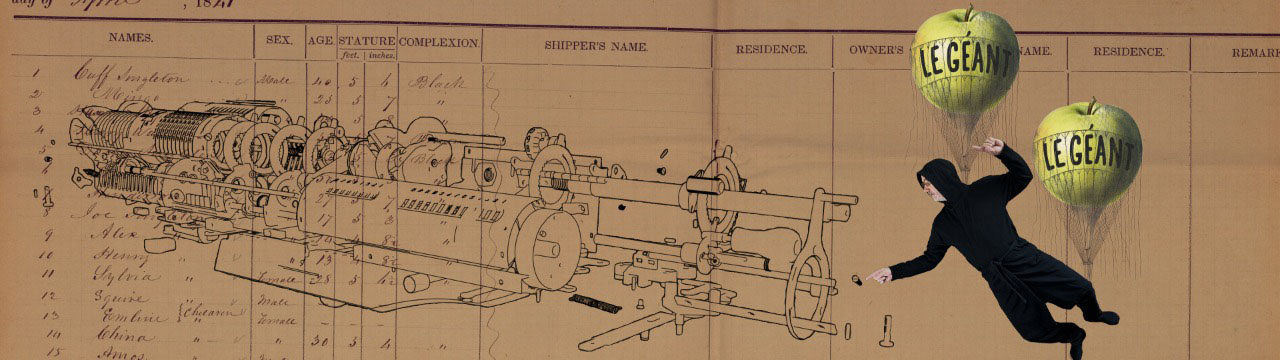

‘Jigsaw’ is a collaborative work using diverse mediums including animation, live performance and video editing to reimagine the theatrical experience

Even WhatsApp has been transformed into a theatrical space. Faye Kabali-Kagwa wanted to create theatre in a place where many of us are now most active – our phones. And thus, emerged The Shopping Dead, a play designed for WhatsApp. The texting platform becomes a virtual stage with the audience constituted as voyeurs on a narrative that unfolds by way of text messages, voice notes, memes, GIFS and photos. Which, if you’ve been privy to certain neighbourhood WhatsApp groups during lockdown, might sound queasily close to home.

Indeed, it’s easy to see how this reimagined festival aims to shine a light on how our relationship with technology is evolving in real-time.

Of course, the Luddites and old-fashioned “wind through the trees” types will be rolling their eyes disparagingly. And, yes, some aspects of live performance might not be possible to recreate digitally. Just as doing a yoga class via your laptop is different to being in a room filled with equally breathless yogis, or running a virtual marathon pales in comparison to the competitive compulsions felt when you’re among 10,000 other runners and hearing spectators cheer you on.

But how else in this time of sustained uncertainty and physical distancing, do we lend support to our artists and keep new ideas circulating?

An online festival offers opportunities to flirt with the arts in altogether new ways, and it would be churlish to suggest that “it’s just not the same” when you’re not there in person when it’s impossible for anyone to be “there” and the alternative is sullen silence.

Besides, the vNAF also offers a chance to revisit past successes and to catch up on missed opportunities. If you never managed to see Brett Bailey’s production of Verdi’s Macbeth in person, the very least you can do is treat yourself to a screening of it at home. A professionally filmed version streams as part of the festival on 1 July.

Owen Metsileng as Macbeth in Brett Bailey’s production of Verdi’s ‘Macbeth’ – photo by Nicky Newman

The Witches in Brett Bailey’s production of Verdi’s ‘Macbeth’ – photo by Nicky Newman

And, on the virtual Fringe, scores of artists who for months have been deprived of income now have an opportunity to distribute their ideas and show their talent to people across the globe, making use of all those easy-to-access platforms we’ve become so intimate with during lockdown.

***

Earlier this week – on Instagram of all places – I watched a video of a wedding between two Scottish men that happened over the weekend in Edinburgh. Thanks to the saying of vows and the exchange of glances and kisses, this cellphone adaptation of a real-life ritual conveyed all the loving sentiment of a typical marriage, but with one strange and seemingly futuristic difference. The nuptials were socially distanced – both grooms were physically present, but the presiding officer spoke from a remote location via a screen.

Unfamiliar as the set-up looked, it took nothing away from the pomp and spirit of the ceremony. It was fascinating, in fact, redirecting the onlooker’s attention but in no way undermining its meaning. Thinking about it later, I realised that this, being a gay marriage, would not even have been possible 22 years ago when I last attended the National Arts Festival.

Times change, technology evolves, humans adapt along with that technology. And we take our art and our rituals and our stories with us.

I only hope that we don’t, with time and sustained physical distance, forget the joy of sharing those stories around literal fires, where the dust kicked up by shamans is real. And where, when an uncouth cellphone dares to ring, a collective sigh of disgust heaves through a living, breathing, physically present audience. DM/ ML

The Virtual National Arts Festival runs until 5 July and can be accessed at nationalartsfestival.co.za.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider