OP-ED

Whither the Christian church? In search of a ‘new normal’ (without the pointy hats)

For the church, the Covid-19 pandemic presents an opportunity to decide what of the ‘old normal’ should be left behind. First must surely be the theology that has allowed the church to condone so much death – the Crusades, the Inquisition, Holy Wars, the burnings, slavery, colonialism, apartheid, the genocides, the institutionalised injustice, poverty, patriarchy, environmental degradation…

“What is this thing that has happened to us? It’s a virus yes. In and of itself it holds no moral brief. But it is definitely more than a virus. It has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like nothing else could.

“Our minds are still racing back and forth longing for a return to normality, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture but the rupture exists.

“And in the midst of this terrible despair it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves.

“Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly with little luggage ready to imagine another world and ready to fight for it.” – Arundhati Roy

Indian Booker Prize-winning writer Arundhati Roy’s quote has inspired many, recently, to reflect on the “doomsday machine we have built for ourselves” and imagine something different.

Is the virus opening a portal, a gateway between our old world and a new one, waiting on the other side? Is the “rupture” to which Roy refers, deep enough to end the many undesirable aspects of the “old normal”?

Graffiti splashed along a wall in Hong Kong suggested that we “can’t go back to normal, because normal IS the problem”. It certainly speaks to me, as does Roy’s challenge that we “can choose to walk through [the portal] dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly with little luggage ready to imagine another world…”

Spiritual writer Richard Rohr has been reflecting in his daily meditations of late on the nature of “liminality” – that space entered between one stage and the next. To occupy a liminal space, is to be on the threshold of a new era or phase. Are we living in such a space? Are we on the threshold of something new? Can we imagine it? Or are the forces that shape us – the lure of the me-first world, the lust for more things, the longing for bigger barns – going to be too strong and corral us back onto the “old normal” doomsday machine?

Arundhati Roy’s words challenge the church inasmuch as they challenge society as a whole. For the church, too, this pandemic presents an opportunity to decide what of the “old normal” should be left behind and what should be taken through the portal to a “new normal” church on the other side.

How does all this affect the church? Who is the church? In this instance, let’s mean the mainstream churches, to which the majority of the world’s 2.2 billion Christians belong. More specifically, let’s focus on the “Western” church, as it’s sometimes called.

Arundhati Roy’s words challenge the church inasmuch as they challenge society as a whole. For the church, too, this pandemic presents an opportunity to decide what of the “old normal” should be left behind and what should be taken through the portal to a “new normal” church on the other side.

Here are some considerations.

First to be left behind must surely be the theology that has allowed the church to condone so much death. And a lot of death has been condoned by Christians… the Crusades, the Inquisition, holy wars, the burnings, slavery, colonialism, apartheid, the genocides, the institutionalised injustice, poverty, environmental degradation – so much of which has been practised by Christians and endorsed by the church down the ages. One hears the refrain in the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young song that goes, “Too many people have died in the name of Christ for me to believe it’s true.”

Much of this deficient theology is rooted in the belief that God is vengeful and wrathful. A professor of theology recently told of her first encounter with God. It was in the lounge of her grandmother’s home where “God” hung on the wall in the form of a large oil painting depicting “Him” as the (Masonic) All-Seeing Eye.

“He sees everything you do, my girl,” said her grandmother, the inference being clear: be good or be damned! The notion that God is up there, watching, judging, ready to strike has plagued our theology, our lives and our self-esteem for generations. Deep in our unconscious, a message has been imprinted that all have sinned and fallen short.

In a further twist of the obscene, not only is this God up there and vengeful, he is a Father to be obeyed, clung to, embraced and loved! The image of battered children clinging on to their abusive father, hoping against hope that one day he will love them, comes to mind. Of course, not only is this Father God intrinsically judgmental, he has a special hatred for sinners such as homosexuals, immigrants, Muslims, protesters, Jews, capitalists, communists – the list is endless.

It’s this kind of theology – the appalling misrepresentation of the nature of God – that has spawned the hypocrisy, the abuse of power, the abuse of children and women, the deceit and exclusion practised within the church over decades.

To blame too, is the fundamental untruth that the church alone is the custodian of the truth – the only and infallible way to God. With this mistaken notion, let’s leave behind the other fundamentalist dogma – especially penal substitution theory, biblical literalism and the Second Coming, among others.

But most importantly, let’s leave behind the church’s support of the patriarchy with its gender-exclusive and gender-excluding roles, behaviours, rituals and traditions that have characterised the church since the 4th Century. And along with the patriarchy, would go the absurd titles, ranks and roles, most of which truly belong to an “old abnormal” church. Let’s leave behind the titles, whether it’s “Your Grace” or “My Lord” or “Father” or whatever – titles that come not from anything that Jesus or the early church taught, but from the kings and queens in whose courts the clergy served from around 350CE onwards.

As a subset of the above, let’s leave behind the masculine language used by the church to describe God. For too long, we have heard of a Father God who saves mankind, and is the hope of men, and so on. Someone once said, “we create the worlds we speak”. Let’s drop the language that perpetuates dominance, judgment and labelling.

Then there’s the matter of the church’s elitism and classism – its bourgeois status. The rot set in, as mentioned above, in the fourth century when the Roman Emperor Constantine was “converted” and turned the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth into middle-class normality. Before Constantine’s profession of the faith, the church was filled with revolutionaries and mystics who mostly met in secret to share their revolutionary belief in equality, freedom, sharing and compassion. After Constantine, as actor and writer Rainn Wilson says; “…the metamorphosis of Jesus Christ from a humble servant of the abject poor to a symbol that stands for gun rights, prosperity, theology, anti-science, limited government (that neglects the destitute) and fierce nationalism is truly the strangest transformation in human history”.

Today, Jesus is even credited when a racist chauvinist wins the White House.

Finally, let’s leave behind the church’s archaic and outdated liturgies, furnishings and designs. I’m so ready to let go of Hymns Ancient & Modern and the over-sung evangelical choruses. And I’m ready to burn the pews and the plush theatre seats. And let’s let go of the fixation that the buildings are the church, and that it’s okay to use them on Sundays only.

Roy suggests that we leave behind us the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies. My list of items certainly includes a lot of prejudice, hatred, avarice, and many dead ideas. But it’s simply a starting point. The challenge will be for the church to let it all go – without becoming amnesic about its complicity in the history it helped to create.

Imagine – a church of people (not buildings) imbued with spirit, living simply and in solidarity with the Earth and all creaturekind. A community of people who are spiritual not religious, simple not grasping, living in solidarity and not separate.

But what luggage should we carry through to the newly imagined church on the other side?

Surely our imagination should turn immediately to the way of life modelled by Jesus himself and so remarkably emulated by countless humble and unnamed followers over the centuries whose lives are the light luggage we need for the journey. Lives like theirs, empowered by a spirit of light and lightness, lived simply and in solidarity with the Earth and those on the edge, are surely the templates on which to imagine a “new normal” church. In other words, let’s not start with what doctrine or dogma we are going to carry through, but rather who are we going to emulate, be like – how are we going to practice faith, not teach it?

Imagine – a church of people (not buildings) imbued with spirit, living simply and in solidarity with the Earth and all creaturekind. A community of people who are spiritual not religious, simple not grasping, living in solidarity and not separate.

Is there a model to assist us in this imagining? Re-examining the model of Christianity practised by the early church would be helpful, but does it belong in the 21st century? What about a more contemporary model that offers a new paradigm and structure for a sustainable and just future?

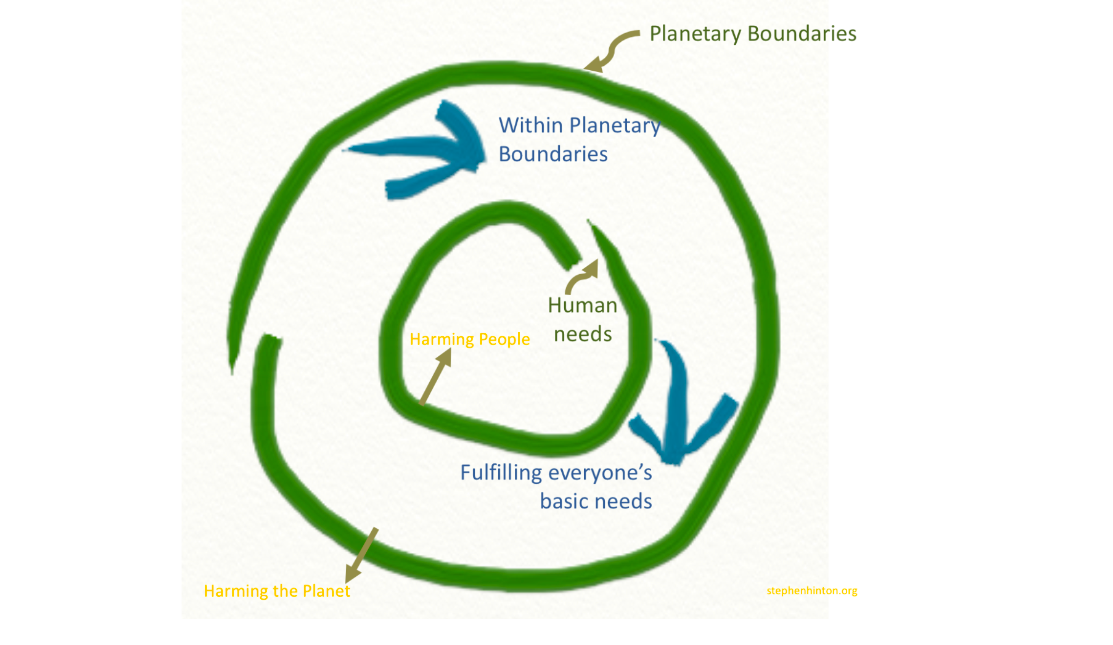

One such model, coming not from the field of ecclesiology but from economics is that from award-winning economist Kate Raworth. Her economic model (and bear with me, for it does have ecclesiological applications, as I will try to show later) is rather spiritedly called “Doughnut Economics”. She is calling for a new visual map and new metaphors to represent the future without compromising future generations. She wants us to move away from linear thinking – from the upward moving “line of progress” ingrained in us all, to a “regenerative and distributive” model designed to engage everyone. And it’s shaped like a doughnut!

Raworth explains, “[H]umanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend – such as a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer. The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries is a playfully serious approach to framing that challenge, and it acts as a compass for human progress this century.”

At the heart of the broken old normal economic system is, says Raworth, our fixation on growth as the single indicator of a successful economy, society or organisation. We need to replace the notion of growth with that of thrive. What do we have to do to ensure that humanity thrives, is her question? Her model is so profoundly simple. Take a look:

Doughnut Economics draws two boundaries – an inner one, we could call the “human rights” boundary, and the outer one, the planetary boundary. The model suggests that living outside both the inner and outer boundary is unsustainable and unjust. Staying within the planetary and human rights boundaries enables the world and all people to thrive. It allows for growth, for diversity, even for some self-interest, but it limits the very limits that unfettered capitalism has never set for itself.

What the model also suggests is that the future is round, not linear. The old normal growth model is a linear line rising higher and higher, driven by the vectors of supply and demand. But we already know that, in ecological terms, “supply” no longer can match “demand”. A round system honours the Earth’s offerings, circulates resources and values “enough” instead of excess. It honours and works towards replacing the current individualistic ego-systems with communal eco-systems.

How would the application of this model challenge and hopefully change the church?

For one, it would envision a church that is round, like the table around which Jesus gathered his loved ones and like the circle into which he invited strangers, sinners, doubters, non-believers, the marginalised and in fact everyone.

Gone would be the pointy church! The old, hierarchical, pyramidal edifice (best illustrated by the absurd looking medieval pointed hats – called mitres – worn by bishops) which we have learned can’t simply be turned upside-down (as some have tried to suggest over the years) would become round.

Round, in a relational way – describing the nature of conversation, listening, enquiry and reflection, with people from around one’s immediate community and with those around the block – who also long to belong.

Such a church would be best illustrated by small communities of equals meeting around a common table sharing resources and caring for each other as each has needs. Oops, oh yes, just as the early church operated for the first 300 years of its life and before Constantine captured it.

A church based on the round model of Doughnut Economics! Round, thriving, inclusive, regenerative and distributive! How extraordinary! Even just the word “round” conjures up a whole range of possible images.

Round as in a mother’s arms – inclusive and embracing. A round God, whose reach is wide and open and in whose embrace there is space for all. No one need live in exile, as Desmond Tutu sought to teach us.

Round as in a model of leadership that is circulated, passed around according to gift and capacity and not title and privilege or gender.

Round as in always looking around – for who may be left out and why?

Round as in solidarity with the Earth – reusing, recycling, redistributing, making things go around so that all have enough.

Round as in a moral compass that reminds us that how we sow, is how we will reap; that what goes around, comes around. Responsible and accountable, transparent and accessible.

Round, in a relational way – describing the nature of conversation, listening, enquiry and reflection, with people from around one’s immediate community and with those around the block – who also long to belong.

And most importantly – round as in centred – in the sense that in the very middle of a circle is a still point – the place of centring prayer – where people gather for meditative, contemplative, rooted listening to the cries of the world, the weeping of the Earth and the healing whispers of God. In this round spirituality, consciousness flourishes, growing ever bigger and bigger in diameter, ever reaching outwards towards cosmic or Christ-consciousness.

The model inspiring this new church is, by definition, flexible, soft, even bouncy. It is practice-based, not theologically driven.

A round church will be less concerned about getting people into heaven, than getting everyone to live justly on planet Earth. In a round church, we look not up into the sky, but around at each other and, seeing God in each person will want to ensure they’re thriving. A round church enables relationships of mutuality, of intimacy, of belonging. In a round church, people see each other’s faces and get to know each other’s names.

A round church doesn’t need buildings. It needs carefully crafted spaces for communal gatherings that encourage personal and collective transformation, spaces that encourage people to thrive, emotionally, spiritually and intellectually.

A round church is, in turn, encircled by larger “rounds” – and so enters readily into partnerships, into alliances with all who also seek to see the world thrive. A round church gathers around the urgent causes of the world, working with others, to fight poverty, environmental destruction and inequality.

The model inspiring this new church is, by definition, flexible, soft, even bouncy. It is practice-based, not theologically driven. At its heart is the longing to see all thrive and when one member isn’t thriving, none can. It fulfils the law of love – to love God, neighbour and self; treating others as one would wish to be treated and that an injury to one is an injury to all.

Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model provides a raft of scientific and sociological theory that needs to be unpacked and applied to the “round-church” model. What are the measures to be used to define the outer and inner circles of a round-church? How will we know it is truly embracing the needs of its members? How will it apply the timeless and often illusive truths taught by its founder, Jesus of Nazareth? Who knows?

But there is a portal and it’s open now. Soon, the pandemic will be behind us and the lure of the malls, the sound of the jet engines, the treadmills of the High Street will dominate our senses once again – and gone will be the opportunity to walk away from the carcasses of our dying religiosity and our polluted faith and to imagine another church and be ready to love it. DM

Chris Ahrends is an Anglican priest, a former chaplain to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, former sub dean of St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town and currently a canon of one of the Anglican dioceses in the Western Cape. He was the founding executive director of the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider