MOMENTS IN TIME

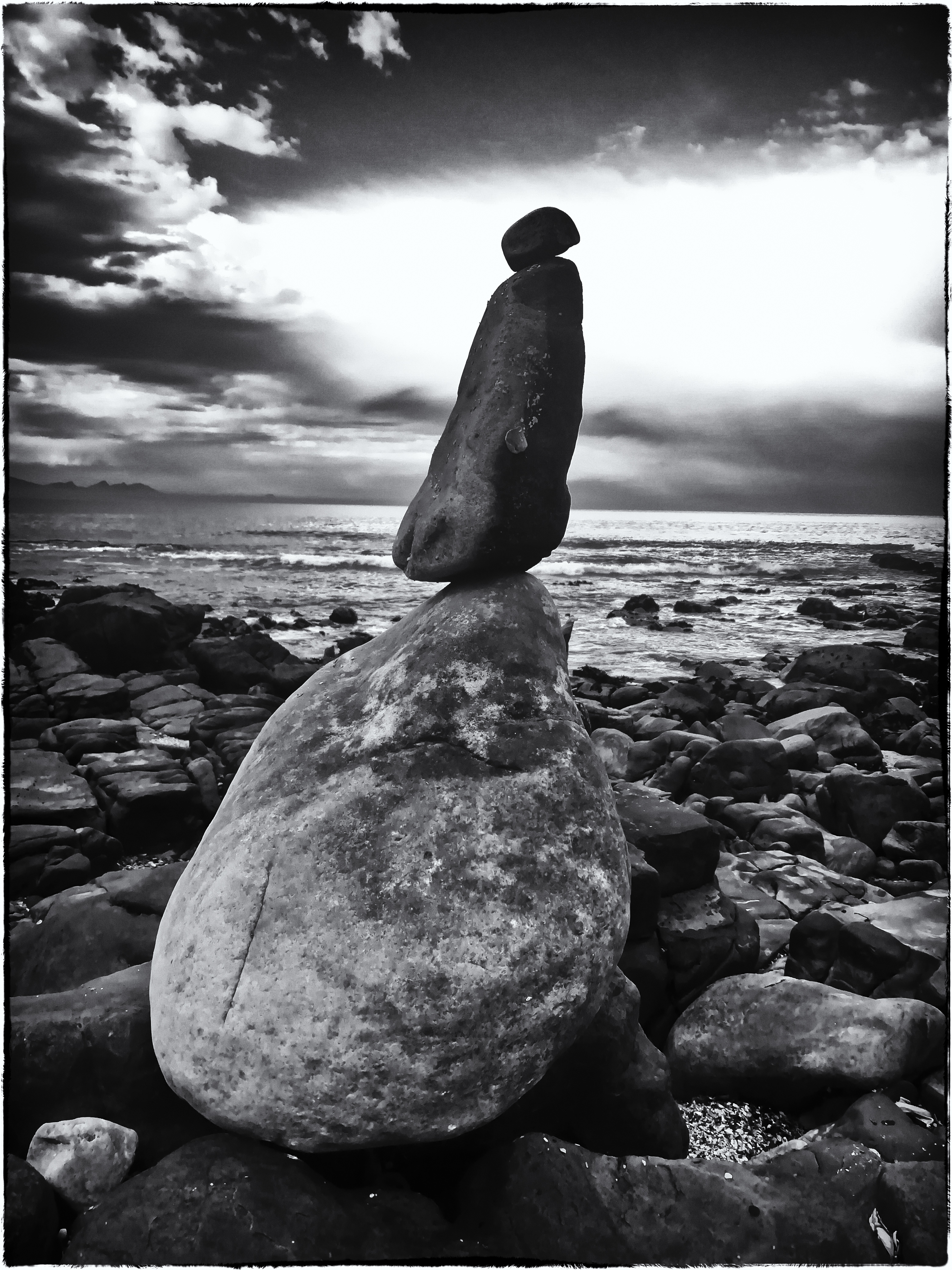

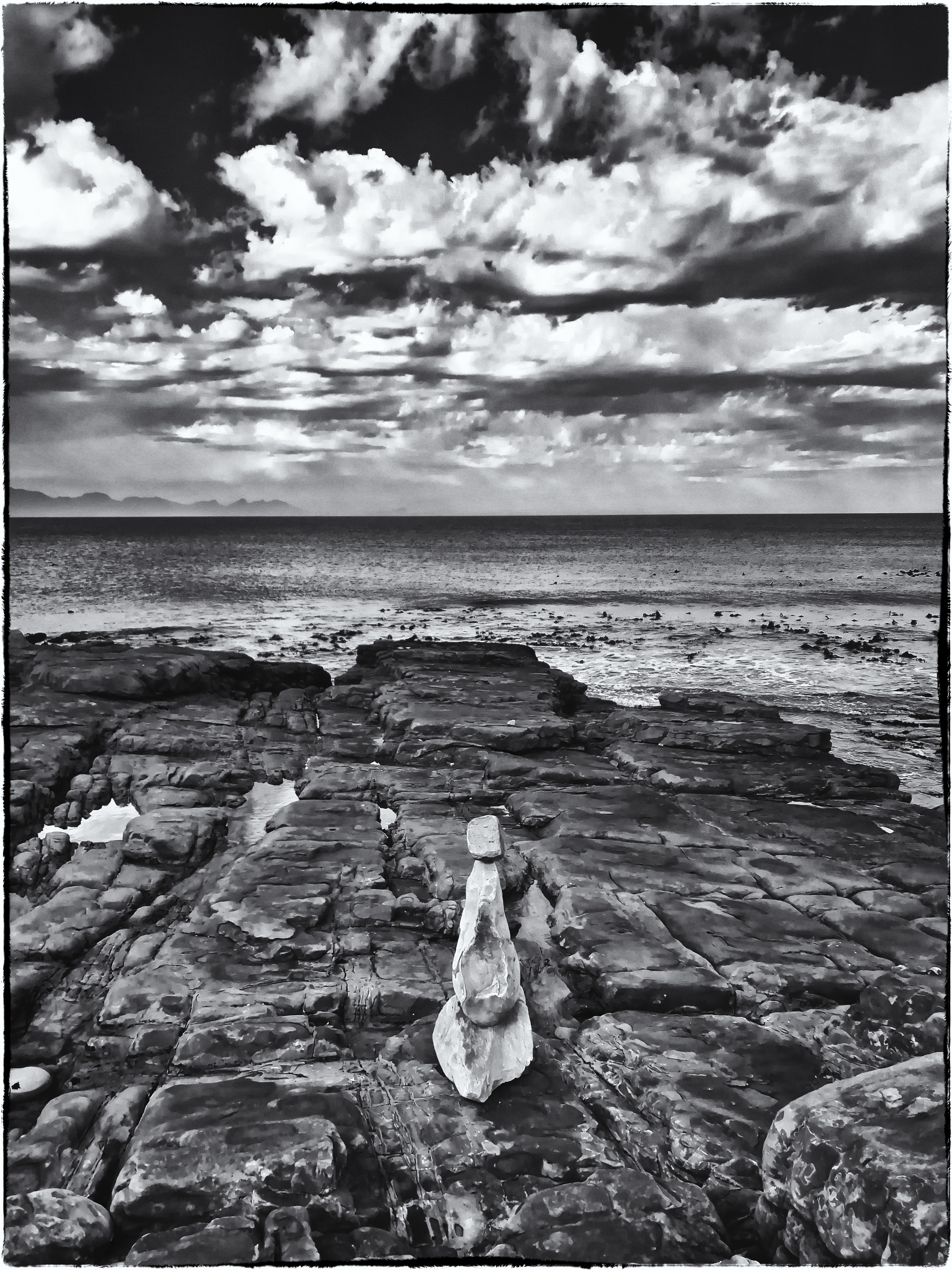

The mystery of menhirs on a Cape Town beach

One feels an inexplicable, ancient reverence in the presence of rock cairns and menhirs. They imply meaning, but we do not know what. Do they give direction or denote time? Are they places of sacrifice or warning?

Carefully placing rocks on top of each other with intent has been part of our culture since we became human. We still fall momentarily silent in their presence.

There’s just something about balanced stones: precariously sturdy, mysterious, and both solid and fragile. Menhirs are extraordinarily prolific in Europe (particularly in Brittany), where around 10,000 have been found and many more presumed to have been lost. It was, however, something of a surprise to find them along the seashore at St James in Cape Town. They were clearly built during deep lockdown in the three dawn hours allowed for exercise.

Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

While we walked, jogged or cycled, someone – I have been unable to find out who – was busily balancing rocks. Not exactly cairns or precisely menhirs, they seem to come out of the same urge to celebrate or mark something important. Or are they to ward off death in the current contagion?

There’s an old Gaelic blessing, Cuiridh mi clach air do chàrn: “I’ll put a stone on your stone.” Before Scottish Highland clans fought a battle, each man would place a stone in a pile. Those who survived returned and removed one. The stones that remained became a cairn to honour the dead. In the Highlands, it’s still traditional to carry a stone from the bottom of a hill to place on a cairn at its top.

Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

In Portuguese legends, stone piles are more magical: cairns (called a moledros) are said to be enchanted soldiers. If a stone is taken from the pile and put under a pillow, in the morning, a soldier will evidently appear briefly before changing back to a stone and returning to the pile.

In the mythology of ancient Greece, cairns were associated with Hermes, the god of overland travel. According to one legend, Hermes was put on trial by Hera for slaying her favourite servant, the monster Argus.

All of the other gods acted as a jury and, as a way of declaring their verdict, were given pebbles to throw at whichever person they deemed to be in the right, Hermes or Hera. Hermes argued so skilfully that he ended up buried under a heap of pebbles – the world’s first cairn.

Menhirs predate that pile by many centuries, however, and are found across Africa, Europe and Asia. Almost nothing is known about the social organisation or religious beliefs of the people who erected them. There’s not even a trace of their language.

By digging around and about these stone erections, we know those societies buried their dead, and had the skills to farm and make pottery, stone tools and jewellery. But the use of menhirs remains speculative.

Until recently, they were associated with the Beaker people, who inhabited Europe during the European late Neolithic and early Bronze Age – around 2800–1800 BC. But recent research into the age of megaliths in Brittany suggests a far older origin, perhaps 6,000-7,000 years ago.

There is another, more modern tradition, that of Zen Rock balancing. It can be a spectacle or a devotion, and involves placing rocks and stones in arrangements which require patience and sensitivity to create stacks which appear to be highly improbable.

- Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

- Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

- Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

- Standing rocks in St James, Cape Town (Image by Don Pinnock)

So the menhirs, cairns or Zen stacks of St James have a long history behind them. Whether they’ll have the staying power of Stonehenge (a henge is a circle of stones) is doubtful, given our storm-wracked skies and pounding surf. But it’s nice to know that someone still harbours the urge to pile stones in the name of mystery, mastery and magic. DM/ML

menhir (from Brittonic languages: maen or men = ‘stone’ and hiror hîr = ‘long’): Standing stone, orthostat, or lith is a large human-located upright stone, typically dating from the middle Bronze Age.

A cairn is a human-made pile (or stack) of stones. The word cairn comes from the Scottish Gaelic: càrn.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider