OP-ED

Mozambique arrest of Brazilian drug kingpin points to southern African shift in global cocaine network

The arrest of the high-level Brazilian drug trafficker Gilberto Aparecido Dos Santos – a close ally of leading figures in Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), Brazil’s largest and most powerful organised-crime group – on 13 April in Mozambique provides further proof of the growing links between South American and southern and East African crime groups.

Recent shifts in the cocaine transhipment route in southern and East Africa suggest a need to re-evaluate the impact that cocaine smuggling is having on the region, particularly in regard to local drug use and corruption in law-enforcement agencies. While East Africa has been the site of large heroin seizures since the early 2000s, the arrest of the high-level Brazilian drug trafficker Gilberto Aparecido Dos Santos, alias “Fuminho”, on 13 April in Mozambique has put the cocaine trade in the spotlight. Together with recent seizures, the arrest of Dos Santos suggests that shifts in the geographic dispersion of cocaine, and the structure of the networks involved, may have occurred.

Why is the arrest of ‘Fuminho’ significant?

Dos Santos is accused of controlling the large-scale shipment of cocaine and weapons from Bolivia and Paraguay to Brazil, as well as running an expansive criminal network in Bolivia which benefits from police protection. He is also a close ally of leading figures in the PCC, Brazil’s largest and most powerful criminal organisation. While some reports have described him as a “leader” of the PCC, it remains unclear whether he is involved with the group as a full member or a powerful ally. He reportedly arranged for the assassination of two leading PCC figures, as well as orchestrating two separate plots to break his close PCC ally, Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho, alias “Marcola”, out of Brazilian federal prisons. Brazil issued an international arrest warrant for Dos Santos in 2018 over his connection to the PCC assassinations, although he had been wanted since 1999 after escaping prison.

The arrest of Dos Santos in Mozambique brought the 21-year manhunt to an end. He was apprehended with two Nigerian associates at a luxury hotel complex in Maputo in a joint operation between the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Mozambican police and the Brazilian federal police. He was then extradited to Brazil on 19 April, a development which Mozambican authorities announced after he had been removed from the country.

According to Mozambican media, Dos Santos had long maintained a presence in Mozambique and South Africa, since both countries were destinations for his shipments of cocaine. This is reflective of the evolution of the PCC, which originated as a prison-based gang within Brazil, into an organisation that has become increasingly involved in international cocaine shipments to Europe and Africa in recent years. Long regarded as a cocaine-consuming nation, Brazil has in recent years emerged as a major international exporter of the drug. In addition to his connections in Mozambique, Dos Santos is reported to have connections to the Italian ’Ndrangheta, for arranging cocaine shipments to Europe.

However, Dos Santos’s exact whereabouts were previously difficult to pinpoint. Information that he was resident in South Africa – reported by Mozambican media following the case and ostensibly stemming from the Brazilian investigation – was at odds with some reports that he was most likely based in Bolivia until late 2019, while other reports indicated that he had shifted his operations to Paraguay. For many observers in Brazil (and Latin America more broadly), his arrest in Mozambique came as a surprise.

Cocaine trafficking to southern and East Africa: An increasingly used route?

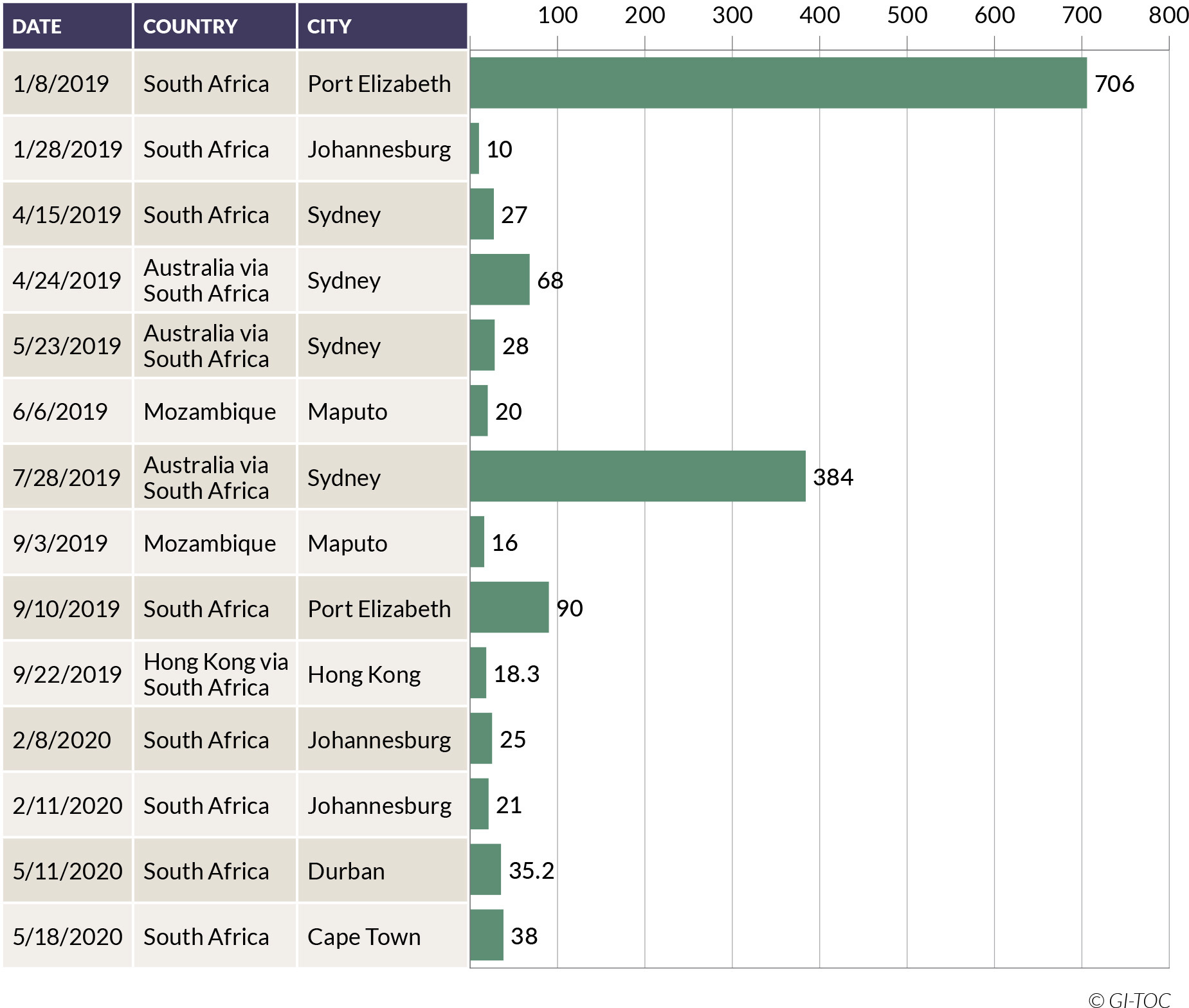

Cocaine seizures made in South Africa and Mozambique, 2019-May 2020. Incidents involving over 10kg of powder cocaine have been included in the analysis. Incidents where it was not possible to determine the weight of drugs seized have been excluded. (Source: compiled from media reporting)

Dos Santos reportedly facilitated shipments of cocaine to South Africa and Mozambique using container vessels. Recent Global Initiative (GI-TOC) fieldwork in the region echoes these reports, finding that cocaine is arriving directly into Pemba port, northern Mozambique and Zanzibar by sea from Brazil. Our research in Pemba found that the entry of heroin and cocaine through the port is seemingly linked to one trader, who owns businesses that rely on imported goods in containers that may also conceal drugs, and through corrupt connections is able to ensure that containers are not searched. The reported increase in cocaine trafficking to Mozambique in recent years may be linked to an increase in the movement of (legal) containerised goods arriving directly from Brazil after a trade agreement was signed between Mozambique and Brazil in 2015.

As with heroin, seizures of cocaine in East Africa are nothing new. In fact, East Africa was identified as a cocaine transhipment region in the early 2000s when there were several large seizures (including seizures greater than one tonne) linked to prominent politicians, as well as reports of Italians linked to drug trafficking who had settled in Malindi in Kenya and on Zanzibar. However, while the link between cocaine, local political figures and Italian networks in Kenya and Zanzibar dates back around 15 years, direct links between Brazilian figures and East and southern African countries have only become apparent in the past five years, with large “symptoms” (such as arrests and seizures) only emerging since 2018.

Another drug-trafficking kingpin – Tanveer Ahmed, alias Galby, a Pakistani national reportedly of Seychellois origin – was arrested in a DEA-led operation in Mozambique in October 2018 and extradited to the US in January 2020. Ahmed’s Mozambique-based network was known for trafficking heroin, hashish and cocaine, with the drugs smuggled in dhows that were met offshore by small boats. The cocaine in these shipments is thought to come from containers shipped to Zanzibar. Ahmed himself faces charges for heroin trafficking but was arrested while in possession of 34kg of cocaine.

Shift towards South Africa?

There have also been notable seizures in South Africa in recent years, although little is known about the networks behind them. On 11 May 2020, around 35kg of cocaine packaged in bricks was seized in Durban port after a tip-off led the authorities to a container from Brazil. A little over a week later, the South African authorities seized 32kg of cocaine, also in bricks, hidden in a truck travelling to Cape Town. In January 2019, more than 700kg of cocaine were seized, again following a tip-off, in a container ship coming from Brazil which had docked at the port of Coega, near Port Elizabeth.

Our understanding of the route that cocaine takes around the region and out of it is also fragmentary. Cocaine coming into Zanzibar is smuggled out using drug mules on flights to Europe, North America and Australia, and in air cargo. Some information also suggests that cocaine is also trafficked overland from Dar es Salaam and Pemba, but we do not know where it goes from there. From other GI-TOC work, we have unconfirmed reports that cocaine is increasingly trafficked from Blantyre and Lilongwe, but we have not established the route by which it reaches Malawi.

As far as transhipment out of Africa is concerned, our previous research has highlighted how the drug mule trade in East and southern Africa, smuggles heroin and cocaine through Entebbe Airport in Uganda, OR Tambo Airport in Johannesburg, and Bole Airport in Ethiopia as key hotspots. Kamuzu and Chileka international airports in Malawi have also been identified as important trans-shipment nodes during recent GI-TOC fieldwork. Networks that smuggle drugs via air mules have primarily been identified as being African. Nigerian networks play a large role in the regional crack-cocaine trade, and in recruiting and using drug mules to send drugs to Asia. But many networks drawing on other African nationalities are also involved.

Since 2017, much larger quantities of cocaine have been leaving South Africa in cargo shipments, mostly to Australia. Australia received nine times the volume of cocaine via air cargo from South Africa than any other country between 2017 and 2018. Since 2019, cocaine has also been smuggled in container shipments. In April 2019, 68kg was found hidden in furniture shipped from South Africa. In the largest seizure, 384kg of cocaine was found in July 2019, hidden in a second-hand Caterpillar excavator. The large size of these shipments suggests that the South Africa-Australia connection was a tested and usually reliable route. With regard to the 68kg seizure in April 2019, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the early findings of the police investigation “point[ed] to the involvement of a larger syndicate, both in Australia and internationally”. Indeed, these large cargo shipments to Australia raise questions about whether there are different networks, possibly European or Latin American, now operating in South Africa, and that are sourcing much larger quantities of cocaine and distributing it to new markets.

How did East and southern Africa become a transhipment route?

Drug trafficking routes along the East African coast. Dotted lines indicate routes which have been suggested by seizures but the Global Initiative have not yet been able to independently verify. (Source: Compilation of Global Initiative fieldwork)

A picture of the cocaine route in East and southern Africa is only beginning to emerge and requires more research. GI-TOC is currently undertaking fieldwork analysing domestic drug-market characteristics and their related supply-chain flows in 10 countries of East and southern Africa. But while the specific history of how each market and route emerged remains to be told, there are some factors that we can safely assume have played a significant role in their development. It is useful to think about these as external and internal drivers of transnational drug trafficking.

Externally, the region is absorbing the impact of increased coca-bush cultivation and cocaine production in South America, both of which reached an all-time high in 2017, the latest year for which there are verified records from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). This has been matched by rising rates of global cocaine consumption, documented primarily in North America and West and Central Europe.

Globally, cocaine-smuggling networks have also diversified and explored new routes as law-enforcement operations reduce the profits generated by old ones. This helps drive the globalisation of drug routes as trafficking organisations adapt to disruption and exploit opportunities as they arise. However, the implications of these shifts for Africa have not been well documented. The UNODC notes that while anecdotal information points to emerging cocaine use in Africa and Asia, “data on drug use in those regions is chronically limited”. Similarly, the UNODC notes that while Africa accounted for only 0.3% of global cocaine seizures in 2017, the “limited capacity of countries in Africa to carry out and report seizures may result in an underestimation of the extent of cocaine trafficking in Africa”. That cocaine markets are growing in “new” parts of the globe (such as Asia and Africa) would also follow from the diversification of cocaine-transit routes, as pointed out in the recent surge in cocaine markets in the Pacific islands, which have sprung out of new routes into the lucrative Australian market.

Then there are the internal factors which make the East and southern Africa region look attractive to smugglers looking for a new way to move their product. In East Africa, high levels of corruption have helped facilitate the entry of new criminal networks into the region – the same conditions that allowed a heroin transhipment route to develop across the region 30 years ago. Corruption has also played a part in South Africa’s development as an important transhipment hub, although this change is more recent, with early research suggesting that this development took place in the past five years when the country’s law enforcement agencies were severely compromised and distracted by state corruption.

Cutting across these vulnerabilities are the opportunities that new trade deals and infrastructure improvements have offered to illicit actors, as well as licit ones. As mentioned above, cocaine smuggling to the region appears to be piggybacking off the increase in licit trade between Brazil and Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa.

Understanding the local impact of transnational transit routes

Dos Santos is one of the most high-profile criminal figures to have been arrested in the region on cocaine trafficking charges, and his arrest suggests that southern Africa is playing a larger role in the global cocaine trade than expected. Emerging – or increasing – transit drug routes deserve our attention as they typically not only take advantage of corruption, but also increase it.

Transit routes also tend to generate increased local consumption of drugs, and the unaddressed public-health impacts of criminalised substances can be severe. Indeed, we are detecting increasing rates of cocaine use across the region, with crack cocaine being particularly popular in Malawi and Tanzania, and cocaine powder popular among the middle class and wealthy in Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa. There are stable domestic retail consumer markets for cocaine in Malawi and South Africa and rapidly growing retail markets for the drug in Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The arrest also raises questions about the inaction of law-enforcement authorities in the region, given suggestions that Dos Santos had a presence in the region for some years. Mozambican commentators have suggested that the speedy extradition of Dos Santos may hamper any investigation into his local networks, and any Mozambican figures who were complicit in his activities and the laundering of drug-trafficking proceeds.

The emerging picture of the facts surrounding the arrest suggests that there may be similar questions to answer in Dos Santos’s other base of operations, South Africa. DM

This article appears in the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime’s monthly Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider