CORONAVIRUS OP-ED

Urgent need for payment deal on non-medical aid Covid-19 patients in private health facilities

As the Covid-19 pandemic intensifies, the demands on the healthcare system will intensify and could result in critical shortages of resources in the public sector. Many non-medical aid scheme patients will need to be treated in private sector facilities. For them, it will be a medical emergency.

Introduction

Global experience shows that success in meeting the healthcare challenges wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic can only be achieved with an integrated approach using the resources of both public and private health systems together in the national interest. This is so in the whole spectrum from screening and testing to healthcare (both beds and healthcare workers) and the eventual emergence and application of a vaccine.

Some governments have addressed this challenge by making drastic changes to the governance, structure and partnerships in the healthcare delivery system, for the duration of the Covid-19 epidemic. The Spanish government commandeered all hospitals and healthcare providers in the country in its strategy to combat the Covid-19 disease. In Ireland, private hospitals, including 2,000 beds and thousands of healthcare workers, were “drafted” into the public health system.

In this article, we focus on a different approach to integrating the provision of hospital resources, so that the healthcare system may meet the challenge of Covid-19.

The inequities between South African public and private health sectors are well documented. And there is little disagreement with the moral argument that the combined resources of both sectors should be harnessed. However, a structured approach to determining and financing the costs of delivering Covid-19 care across the sectors has not yet been derived. This is despite the approval of enabling relaxations to the competition legislation by the Department of Trade and Industry which allows for Covid-19 block exemption for the healthcare sector from the application of sections 4 and 5 of the Competitions Act.

As the Covid-19 pandemic intensifies, the demands on the healthcare system will intensify and could result in critical shortages of resources (hospital beds, ICU beds, ventilators, medical workforce), particularly in the public sector. This has already been quantified in a presentation to the Portfolio Committee on Health. The peak daily demand for ICU beds in the country was projected to be between 4,100 beds (optimistic scenario) and 14,767 (pessimistic scenario) against an ICU bed availability of 3,318 (1,178 public and 2,140 private). A peak need for 7,000 ventilators was projected. There are currently 3,216 (1,111 public and 2,105 private) available in the country. These figures emphasise the acute shortages likely to be experienced in the country as a whole and the public sector in particular. The implications are that many non-medical aid scheme Covid-19 patients will need to be treated in private sector facilities. For them, it will be a medical emergency.

The obligation to provide emergency care

Enshrined in section 27(3) of the Constitution of South Africa is the right that “no one may be refused emergency medical treatment”. There is however no accompanying definition of what constitutes “emergency medical treatment”. Two regulations relating to emergency medical treatment have been promulgated — the Emergency Medical Services Regulations (May 2015 and December 2017) and the Regulations Relating to Emergency Care at Mass Gathering Events (June 2017).

What is clear is that no one may be refused emergency medical treatment by any healthcare provider, healthcare worker or health establishment, according to the Human Rights Commission, the Constitution and the National Health Act. A health establishment means any clinic or hospital, private or public, regardless of its type or location. Normally, private hospitals will stabilise such patients and transfer them to public health hospitals if such individuals do not have adequate medical insurance cover or other means of funding for continued care.

Let us assume that admission of a Covid-19 case to a private facility constitutes such an emergency. Any subsequent attempt at a transfer to a public facility is likely to be met with a non-availability of hospital or ICU beds. And the need to provide ongoing care in that private facility, for which the payment structure and process remains, for now, undetermined.

In the absence of an agreement between the government and private hospitals on the “package of care” or other structured payment models for these non-medical aid scheme patients, private facilities and hospitals will be reluctant to admit them. Alternatively, they could demand “up-front” payments or deposits. It is therefore imperative that the government puts in place payment models and contracting arrangements with private facilities and hospitals. This is essential to ensure affordable access for such patients to resources currently residing in South Africa’s private health sector.

Covid-19 has highlighted the need for South Africa to urgently put in place an integrated health care delivery and financing system. This article explores some of the payment models that could be considered, with the advantages and disadvantages associated with each of the payment models. This does not suggest that finding an appropriate and/or workable payment model constitutes the proverbial silver bullet. There are hard economic realities that must also be faced and these boil down to the fact that we are working within an environment that has limited resources on all fronts and decisions will have to be made on where the best returns on investments, or, value for money, can be obtained. This is a complex and emotive topic that deserves a focused conversation in its own right.

Payment models

The imminence of rapidly increased numbers of Covid-19 patients needing access to care in private hospitals means there is some urgency to put in place contractual arrangements based on a clearly stipulated payment model.

The choice of the payment model to be used for providing these services is an important one. The incentives, the management information system and administrative requirements of the various models are different and these can have profound effects on the quality, appropriateness and cost of care. One key goal of the payment model is to find the optimum balance between provider incentives and risk, so that appropriate and cost-effective care is encouraged while inappropriate, ineffective and expensive care is minimised or eliminated.

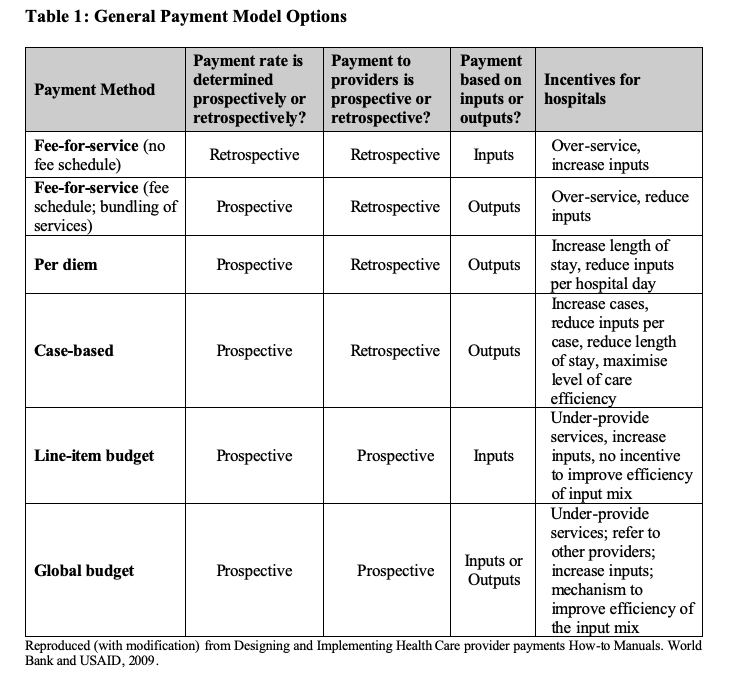

Drawing on the manual for Provider Payment Systems published jointly by the World Bank and USAID, the types of hospital payment methods, characteristics and incentives that may be used to pay private facilities and hospitals, are summarised below in Table 1.

With the Fee-For-Service system (non-scheduled and scheduled), the hospitals would be reimbursed for each item of service or procedure that is provided to the patient while hospitalised. A large portion of the current medical aid scheme contracting with private hospitals in South Africa is based on such a Fee-For-Service (FFS) system. The South African Competition Commission’s Health Market Inquiry found this FFS system to be highly inefficient and open to, if not stimulating, supplier-induced demand. The information, administrative and management oversight requirements of the FFS payment system are high. It also increases the “cost of care” by contracting administrators and managed care organisations for these non-clinical services.

The Per Diem payment system involves paying a fixed daily rate that does not vary with the amount of services provided but is specific to the level of care, eg ICU day vs general ward day. Relative to the FFS payment model, the incentive to over-service is reduced, but the incentive to increase the length of stay, or “game” the level of care, remains. The Per Diem system is administratively simpler to manage than the Fee-For-Service payment system.

With the Case-Based model, a standard payment is made on a per-case basis. It provides the hospitals with an incentive to minimise the resources used for each case. Without an allowance for variation in case mix, hospitals would be incentivised to admit only less severe cases. With an allowance for case mix, hospitals would be incentivised to “up-code” and increase the number of more severe cases. The Case-Based payment model must be in alignment with the “Diagnostic Related Groups” (DRG) model. This is the preferred model for contracting hospitals in the proposed National Health Insurance scheme. A Case-Based system would be administratively and operationally complex. It requires consistent and comprehensive data, and a computerised information system that records and groups cases into payment categories.

With a Line-Budget payment model, the private hospitals would be paid a fixed amount for a certain period of time to cover specific inputs costs (eg personnel, utilities, medicines and supplies). With a Global Budget payment model, the private hospitals would receive a fixed payment to provide a set of services that have been broadly agreed upon over a given period. Given the huge uncertainties regarding patient numbers and the numbers of uninsured that would need to be treated in private facilities and hospitals, neither of these two approaches can be considered as pragmatic for the current Covid-19 epidemic. The experience of contracting arrangements with the private health sector during the Covid-19 epidemic may well provide valuable data and information which will allow for the piloting of different payment models post-Covid-19.

Payment model options for South Africa during the Covid-19 epidemic

Fee-For-Service payment (with a negotiated fee schedule and bundling of services) is currently the dominant payment model for the South African private hospital sector. Adopting this model would allow private hospitals to charge the rate that they have in place for South African non-medical-scheme patients. The government could retain this payment model, but negotiate what it considers to be an appropriate rate for a defined or agreed package of services. Specific strategies would be needed to reduce the incentive to “over-service” inherent in this system.

The adoption of the Per-Diem model or Per Case model dilutes this risk and would be more in keeping with longer-term government thinking. The challenge associated with the Per-Diem model is to determine the “bundle package of services” that would be utilised per day and then price those services for different levels of care (ICU days, general ward days, and so on). Currently, such prices/tariff structures are not in place. For the Per Case model, there is a further challenge of determining case types by severity, the “bundled package” of expected services and the related “normal” length of stay for each severity type. While these challenges are formidable, they are not insurmountable.

In Namibia, where the challenges faced were very similar to these faced in South Africa — notwithstanding the difference in the size of the private healthcare industry — a payment and tariff negotiating model has been developed which allows for the following:

- Negotiating parties to agree (in an open and transparent way) on the expected utilisation of specific services and length of stay for differing level of disease severity (Mild, Moderate, Severe, Very Severe);

- Provide for mechanisms whereby the combinations of services originally agreed to can be updated as experience is gained; and

- Apply an agreed tariff rate for the services to derive costings for all three payment models (Fee-For-Service, Per-Diem, Per Case).

There is an urgent need for a similar approach to be developed for South Africa.

Stark choices

It seems unlikely that the South African government will adopt the “commandist” approach adopted in several other countries. Which means a negotiated arrangement is both more likely and, we would argue, more desirable in the long term for the evolving NHI project.

There are two main consequences of the state not making a clear decision on an appropriate model.

In the first, the state faces a non-negotiated FFS model, with dictated terms and all the inherent flaws of this model, including unbundling of procedure codes used, over-servicing and the arbitrary pricing of items completely unrelated to their real costs. The costs then payable by the state are likely to be substantially beyond the cost of equivalent services provided in the public sector.

In the second and more serious consequence, the default billing practice of private hospitals is implemented. This means the uninsured patient gets the bill and the legal responsibility to pay it. However, there is an alternative. Negotiate and adopt a clear proactive choice of pricing model. In this, the state has the opportunity to lay down realistic terms for the fair pricing of a particular basket of items. For example, the known/real cost of a one-week stay in a public ICU bed could help to tailor an equivalent FFS basket of services to reach a meaningful tariff.

We know that at the peak of the Covid-19 epidemic, public hospitals are unlikely to be able to accommodate all the patients needing hospitalisation. If South Africa is to ensure that all Covid-19 patients are able to access the required accessible, affordable and appropriate hospital care, the South African government must engage with the private hospital and other private sector provider groups to develop suitable contracting arrangements and payment models as a matter of urgency.

Government and the private health sector need to talk to each other before Covid-19 infections peak and the public hospitals are overwhelmed. DM

Geetesh Solanki is Specialist Scientist at the Health Systems Research Unit, SA Medical Research Council (SAMRC) and an Honorary Research Associate in the Health Economics Unit, University of Cape Town; Reno Morar is Chief Operating Officer, University of Cape Town; Neil Myburgh is Acting Dean of the Dental Faculty, University of the Western Cape; and Johann Van Zyl is the founder and owner of a clinical risk management consultancy, Clinical Governance Services (Pty) Ltd. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their institutions.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider