Coronavirus: Lockdown Op-ed

The hidden struggle: The mental health effects of the Covid-19 lockdown in South Africa

In the recent large-scale Covid-19 democracy survey conducted jointly by the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Change and the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State research division of the Human Sciences Research Council, it was found that 33% of South African adults were depressed, 45% fearful, and 29% lonely during lockdown. We find that the chief driver is hunger, consequent on poverty. Yet, on average, the overall mood is less negative among black Africans than other race groups. This article presents and tries to explain these findings.

Internationally, concern has been mounting about the mental health consequences of long-term high-level lockdown. The full or partial lockdown in response to the Covid-19 epidemic, by more than a hundred countries spanning nearly half of the planet’s population, has been described as “the largest psychological experiment in the world”. It is an experiment few would volunteer to join. An April 2020 academic article warns that “It appears likely that there will be substantial increases in anxiety and depression, substance use, loneliness, and domestic violence“. Globally, such emphatic assessments have contributed to calls for a calculated easing as soon as feasible and relatively safe.

In South Africa, among the most unequal societies in the world, the circumstances of people caught up in the confinement differ dramatically: ranging from a minority of comparatively well-off families or individuals in suburban houses, apartments or clusters, to mainly less well-off families in townships, informal settlements and rural areas. The poorest depend on child support grants, grandparents’ old age pensions, and remittances. For such families with scant savings, and with their wage-earners often dependent on casual or informal-sector employment, the economic effect of confinement has been devastating. This has been painfully visible on TV in the lengthening queues for food-parcels.

However, the way in which these factors impact on our population’s mental health has received little statistical attention locally. An HSRC-led research consortium has indicated that South Africa is in a “moment of psychological crisis”. Developing an evidence-based psychological profile of the mental health and its determinants of South Africans under lockdown is now critical to adding these largely hidden needs to the claims upon resources.

This article accordingly focuses on a number of variables related to mental health carried in an online survey conducted by the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Change in collaboration with the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division of the HSRC. The analysis uses data from all three phases of the survey, which ran from 13 April to 4 May. The changes in the analysis variables are seen below to have been slight. The survey employed opt-in cell-phone sampling; but the 12,312 complete responses received have been weighted to StatsSA demographics; so the results are indicative of the national situation.

Specifically, respondents were asked the following to capture different aspects of their psychological state: “Now we want to ask you a question about the effect of the lockdown on you emotionally. Which of the following emotions have you felt often during the past week?” This was followed by a list of different emotions to which they answered yes or no.

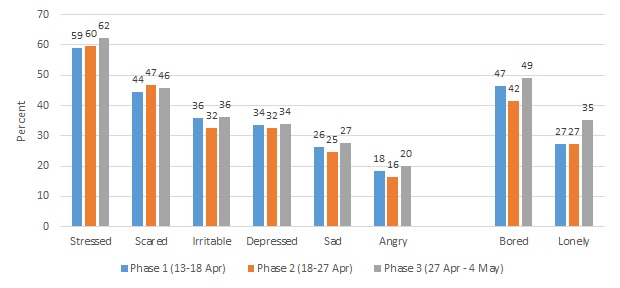

As Graph 1 reflects, on average across the three phases of the survey, some 60% of South Africans under Covid-19 are frequently stressed and 46% are scared. Around a third are depressed (33%) or irritable (35%). And between a fifth and a quarter of adults have experienced sadness (26%) or anger (18%).* From the right of the graph, it is evident that 47% have experienced boredom and 29% have experienced loneliness under lockdown. As a benchmark, depression has been clinically measured at between 18% and 27% in less unusual times, so it is likely that there has been an appreciable increase.

Differences between the phases of surveying have been slight, varying by only 2-4 percentage points, except boredom and loneliness, which have fluctuated in a 7-8 percentage point range. This indicates that many South Africans have been regularly experiencing a range of negative emotions under lockdown with little sign of abatement. However, except for loneliness, our data does not point to a surge in negative emotions over the three-week period.

Graph 1: The mood of South Africa under lockdown, by wave of surveying (% experiencing each emotion frequently during the week prior to the interview)

We may illustrate these eight emotional states, with poignant answers to our invitation to survey respondents to share, in their own words, “the worst thing” about lockdown:

Scared: “There is no limit to the people coming into the store. So it put me and my colleagues at high risk to get infected.”

Stressed: “Knowing that my parents are stressed about where we are going to get our next meal if the President decides to extend the lockdown.”

Depressed: “The lockdown has affected my business harshly, production has stopped all together. At times I feel depressed, feel like life is not worth living anymore.”

Sad: “Watching my kids get sad and angry at the restrictions and I cannot take them outside.”

Irritable “No take aways, no liquor stores or cigarette sales. Getting frustrated with my household and enormous pressure due to school children missing a lot of work.”

Angry: “Being locked even when I feel like both going somewhere I want to – it makes me angry so much.”

Bored: “Not being able to go to school or not seeing my friends. Also it gets boring cause we don’t have WiFi or data.”

Lonely: “I cannot really help my elderly mom and she is very lonely.”

There are relevant nuances underlying this national pattern of negative emotional experiences. Women may be psychologically affected differently from men by some of the aspects of the Covid-19 lockdown. They are more depressed than men (36 vs 31%) and more apprehensive (50 vs 42%). Perhaps this is because they almost certainly bear the brunt of the extra child-care. They report being somewhat less lonely (27 vs 30%), perhaps for the same reason. And they are not more stressed, irritable, angry or bored. These percentage differences may not be large but they are statistically significant, and they “add up”.

As for generational differences, young South Africans seem more prone to boredom and anger relative to older adults. For instance, an estimated 59% of 18-24 year-olds felt bored compared to 29% of those 65 years and above. The difference was a more nominal 10 percentage points in the case of anger (22% among 18-24 year-olds vs. 12% among those 65+ years). We also find that fear, stress and depression taper off after the mid-40s. This suggests that the psychological effects of lockdown are being experienced differentially by age group.

There are other important variations to disentangle that reflect our rainbow nation. In our sample, more than half (53%) of white respondents reported household incomes above R10,000 per month, compared to merely 6% of black Africans. That, sadly, was expected. Yet the proportion of black African adults reporting irritation was only 29%, half that among white adults (62%)!

Why might this be? (Readers may prefer to come back to the supporting percentage contrasts, in parentheses.) After all, nearly identical proportions from both groups think the lockdown has not been too harsh (72 vs. 73%), and trust or strongly trust the President (85 vs. 82%). Part of the answer is to “follow the money”. Whites are much better off than black Africans, as we saw. Yet many more of them (71% vs 47%) think the Covid-crisis will worsen their financial situation. Moreover, those thinking their financial situation will worsen, or already has worsened, comprise a much larger proportion among those irritated than not (63% vs 44%).And this may also explain why people with post-matric qualifications emerge as being considerably more irritable under lockdown than those with matric, or less (50%, 41% and 28% respectively): thanks to apartheid policies, white adults still tend to access more education.

Now, as the blizzard of percentages in the recent paragraphs confirm, eight variables are a handful to analyse at once. To dig deeper we need to simplify. Based on the patterning in the data, a statistical technique called factor analysis shows (for the first wave, and confirmed in the next two) that there are actually two underlying psychological factors at work.

The one construct comprises the six conditions – including being scared, depressed, sad, and irritable – shown on the left of the graph. We may define psychological distress as the number of these conditions that a respondent says they are experiencing. The other phenomenon comprises the two conditions on the right of the graph, boredom or loneliness. We define the other construct, isolation in the same way. Since these are composite measures, their levels are arbitrary. What is important is what they allow one to investigate.

Adding in another statistical technique, called regression analysis, we are able to tackle a key issue: among the range of topics covered in the survey, what are the chief drivers of these phenomena, so that their components may be mitigated?

It turns out that much the strongest predictor of composite psychological distress is sheer hunger. This is, tragically, no surprise. A previous Daily Maverick op-ed from this survey, reported the alarming extent of the problem. In response to the “worst thing” write-in option, the most frequent response, 31%, was not having enough food to eat: “I am an unemployed mother of three kids and I don’t know where my next meal is coming from”; “I am living with a granny and hunger is killing us”; “Hunger and the fear of dying out of hunger since no income”.

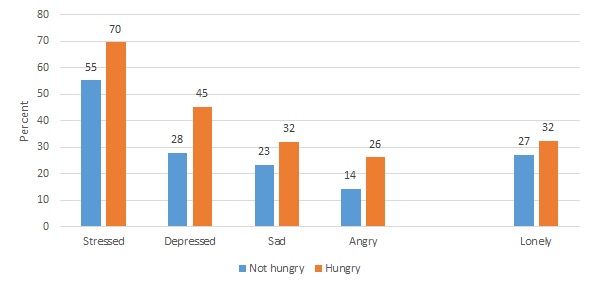

Graph 2 displays the strongest effects of hunger on the indicators of psychological distress, drawn from the left side of in the earlier graph. Among those who are hungry, sadness is 9% higher, anger is 12% higher, stress is 15% higher, and depression 17% higher, than among those not hungry. The effect on the indicators on the right is less strong. Nevertheless, while boredom is not increased by hunger, loneliness is 5% higher.

Graph 2: The effect of hunger on the mood of South Africa under lockdown (% experiencing each emotion by experience of hunger, average across all three survey phases)

To mitigate hunger, food parcels have been the most immediate measure, but they are not sustainable in the long term and are difficult to implement comprehensively. Rather, one needs to identify hunger’s drivers in turn. These are not the focus of this article. But one notes that hunger correlates dramatically with income: 19% among those earning more than R2,500 per month are hungry, compared to 42% of those earning less. And for income, apart from grants, employment is obviously critical. Hunger is at 22% among those employed full or part time, but rises to around 42% among those unemployed or only in casual work. This signals the importance for mental health of continuing the phased re-introduction of access to work and wages, as fast as this can be safely achieved.

A perhaps unwelcome finding is that both psychological distress and isolation are significantly lower among Covid-denialists, who believe that the threat is exaggerated. The converse is more intuitive: those who believe the threat is real understandably tend to feel more fearful, distressed, and alone. This may relate to the extent and nature of their media use, and needs more research.

Surprisingly, people’s differing accommodation seems hardly to affect their psychological distress. The diversity makes it more difficult to analyse. However, it seems that people living in hostels or student residences, or in an informal settlement dwelling without a yard, most experience both loneliness and boredom. Clearly, the company of others in lockdown and being able to get outside make a huge difference.

A remaining indicator in the regressions was both quite strong and seemingly contradictory. Black Africans reported significantly less psychological distress than other population groups, by between 4% and 17% on the several questions. (We dealt in detail with the irritation question above.) Yet we seen how, given South Africa’s continuing post-apartheid inequalities, black African adults on average earn less, therefore experience more hunger, and therefore should be experiencing and reporting more distress. In fact, both contentions are true. In the latter “causal chain” the successive links are strong, and their cumulative correlation is positive. But its total effect is indirect, and weaker than the direct negative correlation between being Black and being depressed. Perhaps this fact reflects larger households and stronger family cohesion and resilience; about which – as they say – more research is needed.

Patterns among data such as the foregoing are potentially powerful because they are representative of South African adults; and may therefore be persuasive and helpful to democratically accountable authorities in their decision-making. But their force is greatly enhanced if they are “ground-truthed” by authoritative eye-witness testimony. Many of our statistical insights were remarkably captured in a blog from a family GP in a small, multiracial seaside town: “Consults are taking a lot longer because people are so lonely, so bored, so stressed… People who have lived alone for seven weeks with no interaction. They are not okay. Moms who are desperate. People who have been told that this is their last salary and then it’s UIF, if they can access it. The fear, the anger, the depression… It is so real and really scary.”

This scary, unavoidable worldwide experiment will end. But as both our President and the South African Depression and Anxiety Group have warned, in their different domains, it requires concerted attention and the correct measures. Mental distress and isolation, no less than their prime socio-economic determinants, must be part of the mix. DM/MC

This is one of a series of articles by researchers from the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Social Change (CSC) and the Human Sciences Research Council’s Developmental, Capable and Ethical State division (DCES). Data comes from the online multilingual Covid-19 Democracy Survey. This can be undertaken, free of charge, by anybody in South Africa aged 18 or over with access to the internet. Go to:https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/CovidUJ (https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/CovidUJ). Results are weighted by race, age and education, making them broadly representative of the population. Phase 1 of the survey covers the days from 13-18 April, Phase 2 from 18-27 April, and Phase 3 from 27 April to 4 May. See https://www.uj.ac.za/newandevents/Documents/UJ HSRC summary report v1.pdf

(https://www.uj.ac.za/newandevents/Documents/UJ%20HSRC%20summary%20report%20v1.pdf).The survey uses the #datafree Moya Messenger App on the #datafree biNu platform.

Mark Orkin is an Associate Research Fellow in the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg and a Visiting Professor in the Development Pathways to Health Research Unit, Wits University, and headed Stats SA in 1995-2000. Benjamin Roberts is a chief research specialist and co-ordinator of the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division at the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). Narnia Bohler-Muller is divisional executive in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division at the HSRC and adjunct Professor of Law, University of Fort Hare. Kate Alexander is Professor of Sociology, South African Research Chair in Social Change, and director of the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider