OUR BURNING PLANET

With a little help from leeches, scientists may have found a coronavirus they don’t know. But does it matter?

Blood-sucking, worm-like creatures from a remote Bornean rainforest pave the way for a rogues’ gallery of viral discoveries.

An early-warning system using wild leeches as a type of “sniffer dog” seems to have flushed out a whole cast of novel wildlife viruses, a new paper by an international research team claims.

As Covid-19 soars past 4-million cases globally, a discovery within this trove of pathogens may be a novel coronavirus, one that would be unknown to the science of emerging infectious diseases.

Writing in a preprint study on online research forum bioRxiv, the scientists warned that this novel coronavirus could be prowling in the blood of sambar deer – an antlered Asian species heavily poached for the bushmeat trade. Led by the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, which worked with several European research institutions, the study has been submitted for peer review and publication.*

Over New Year, authorities had isolated SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus that causes the respiratory disease Covid-19 – at a market selling wildlife in Wuhan, China. Although many “origin” theories have been floated (some less reliable than others), the market’s early cluster of environmental samples have provided the most complete, if inconclusive, forensic evidence yet.

China’s political brass subsequently slapped a ban on trading and eating terrestrial wildlife, highlighting how vital it is to do imaginative experiments that can help us dip more than a toe into the mostly uncharted universe of naturally occurring viruses.

Setting out to find “unknown” pathogens floating in wildlife DNA, the Leibniz et al team took a stab at exactly that – or, to be more precise, the leeches that feed on mammal blood.

Their voyage of discovery was a dramatic departure from previous environmental DNA studies, all of which focused on known disease-causing organisms.

When the Leibniz scientists dived into the nucleic acids of the leech samples, as many as a quarter of these spat out genetic signals of coronavirus. But here’s where these initial results yielded real intrigue: the gene sequences showed a high similarity to an important segment in a known bat betacoronavirus.

To this team of scientists, they had lucked upon a telling clue – something virologists do not see every day in a pandemic. This tiny segment looked like a possible relative of the very virus stripping the scaffolding of society as we know it.

Was this a sign that governments everywhere should dust off their microscopic Berserker probes and aim them at the new alien intruder?

Maybe. Maybe not.

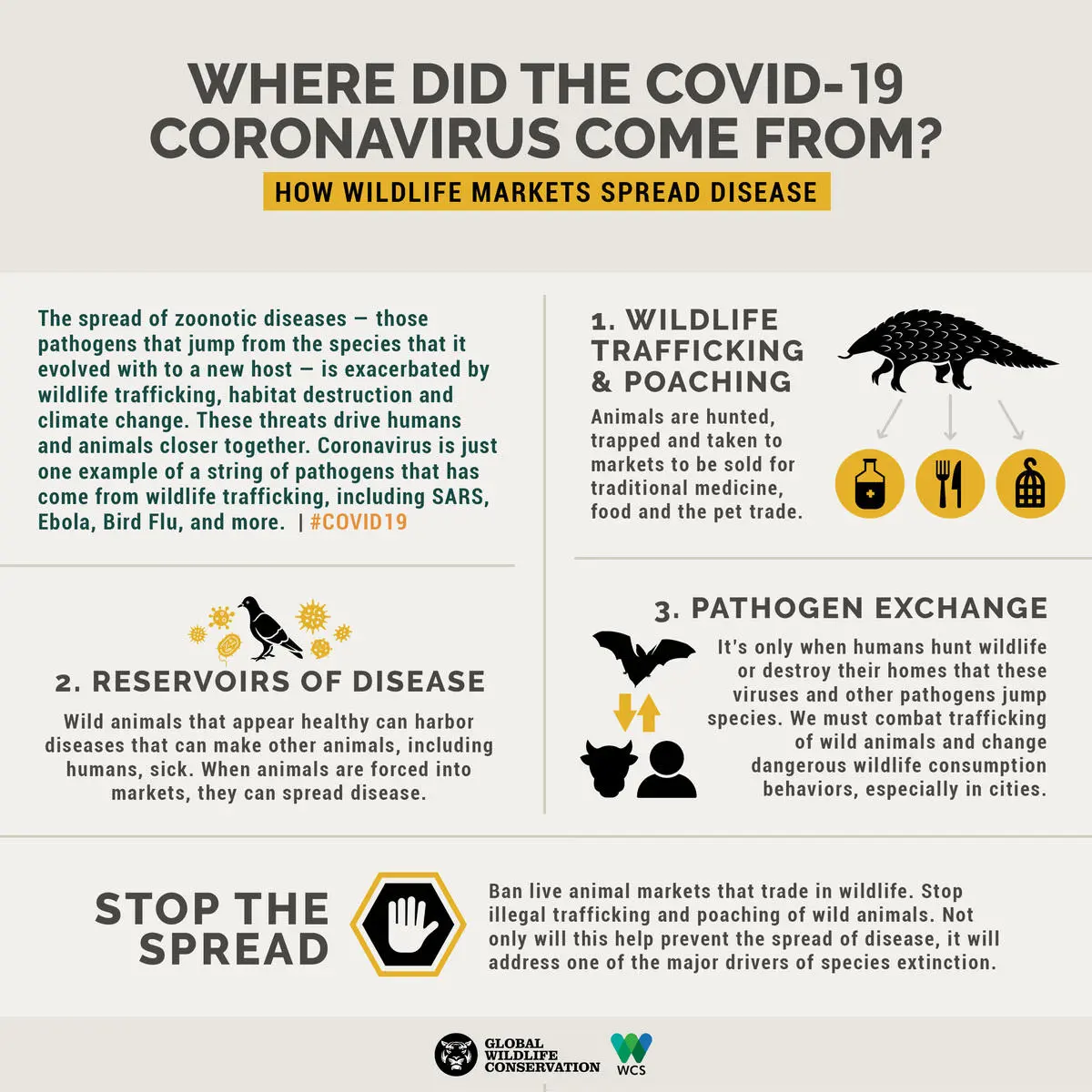

‘It’s only when humans hunt wildlife or destroy their homes that these viruses and other pathogens jump species,’ say the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Global Wildlife Conservation group in this awareness campaign. (Image: The Wildlife Conservation Society and the Global Wildlife Conservation group)

Grandma Moses parts the seas of virology

As research tools they may seem odd, even grotesque, but the study’s Haemadipsa leeches take an early cue from “Grandma Moses”, the giant Amazon leech (Haementeria ghilianii) that helped part the waters of medical science by spawning a body of research – and hundreds of offspring – at the University of California-Berkeley in the 1970s.

Like their pioneering relative Grandma Moses, Haemadipsa leeches make excellent sniffer dogs for science, because they’re remarkably efficient hunters that sup on the blood of mammals – domestic, wild or human.

These heat-seeking missiles move with startling speed across flora and the forest floor, by sucking their mouths and bottoms to natural surfaces in a spasmodic dance of loops and expanded lines. The pièce de résistance of this dancer’s predatory polka is isolating a medium-to-large mammal host and engorging itself on a meal of its blood.

To conduct their investigations, the scientists harvested a small army of tiger leeches (Haemadipsa picta) and brown leeches (Haemadipsa zeylanica) from Malaysian Borneo’s Deramakot Forest Reserve, a logging and ecotourism concern sandwiched among swathes of rainforest to the far north.

Next, the leeches were corralled by species and location into bulk samples before being carved into bits and soaked overnight at high temperature. Nucleic acids were extracted with blood-and-tissue kits, producing gene sequences. High-performance molecular analysis scrutinised the DNA, while the scientists also looked for matches in public data systems designed to characterise new viruses and emerging infectious diseases.

The gene sequences, which took half a decade to gather and analyse, rewarded the researchers with preliminary evidence of no fewer than six viral families capable of infecting vertebrates.

Novel coronavirus pops up in bushmeat (and it’s not pangolins)

One of the most dominant was Coronaviridae, that lethal family of single-stranded RNA viruses with one existential goal – hijacking other forms of life with a killer army of microscopic problem kids, otherwise known as coronavirus species.

However, as the Leibniz scientists wrote, their evidence “did not cluster in any of the four clades representing the known Coronaviridae genera, suggesting it may represent a novel coronavirus genus”.

Curiously, this evidence was not Covid-19’s infamous creator, SARS-CoV-2. It was not any of its vicious predecessors in the betacoronavirus genus, either. Ostensibly jumping from bats via intermediate vectors, each of these betacoronaviruses has exacted an escalating death toll. In 2002/3, SARS-CoV came to humans via masked palm civets sold at Guangdong’s animal markets (750+ people dead). In 2012 onwards, Mers-CoV came to us via camels (850+ people dead, and counting). And, in 2020, Sars-CoV-2, possibly via pangolins according to US research (first reported globally by Daily Maverick in February), has snuffed out the lives of some 280,000+ souls.

If confirmed by peer review, this latest trail of Coronaviridae crumbs would be a fresh umbrella group of coronavirus species. Thus, a brand-new coronavirus genus detectable in the deer family, because nearly 90% of the samples “with the potentially new coronavirus genus yielded deer sequences, specifically sambar (Rusa unicolor)”.

To find out more about sambar and its relationship with humans, Daily Maverick consulted the IUCN Red List, the global authority on the conservation status of species.

An elegant beast with thinly curved antlers and a shaggy coat ranging from light to dark fawn, the sambar deer cuts a memorable figure. It is Southeast Asia’s largest deer. A truly beautiful, imposing trophy specimen. And, not surprisingly, we found that it was advertised as an introduced species on the websites of hunting outfits operating in the southern hemisphere, notably in South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Sambar is also a fixture in the US trophy-hunting industry, as promoted by several US-based websites offering guided services to shoot these animals.

An Austrian/US website claiming to offer ‘more than 4,801 hunting trips from 744 outfitters’, including ‘13 hunting trips from 5 outfitters’ for sambar deer. It says its mission is to ‘bring transparency into the hunting market while supporting the conservation of wildlife all around the world’. (Image: www.bookyourhunt.com)

Sambar is also sought-after for its meat in Malaysian Borneo, and native to Yunnan province, that region in southwestern China to which the Wuhan Institute of Virology traced the origin of Sars, within the recesses of a cave providing refuge to horseshoe bats. In fact, sambar “is probably near the top of chosen wild meats” in most of its natural range and “vulnerable to local extinctions” through “uncontrolled illegal hunting”. It is in such demand that TRAFFIC, the wildlife-trade monitoring network, together with other world conservation groups, have called for wild sambar to be uplisted to Endangered.

Daily Maverick consulted South African virology expertise on the significance of the Leibniz study’s early results. The reaction was reserved.

“They simply found a small piece of a coronavirus genome, which quite closely matches some known coronaviruses,” said Professor Darren Martin, a University of Cape Town virologist. Martin’s software is used worldwide to study recombination patterns in microbial genomes, and to analyse data from emerging and even re-emerging viruses during major outbreaks, such as the present pandemic.

Martin pointed out that it was particularly difficult to establish how closely this segment “matched these other coronaviruses because the figure given is [only] for the best-matching segment of the virus”.

That is, only an upper-limit 73% match “in that one, small, long fragment”.

However, he did agree that it was “possible that this small genome fragment represents a new coronavirus genus”. It was “definitely” even a “good starting point for us to find the full genome and track down the most likely hosts of this virus” – but the study would need to go a step further to convince the critics who “mattered”, he argued.

“Properly filling in a blank would be fully sequencing the virus genomes within those species and not just leaving the discovery at the we-found-a-fragment-of-a-virus-genome phase.”

Professor Wolfgang Preiser, head of Stellenbosch University’s medical virology division, agreed that this virus would need to be “characterised more fully”. Then the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses would have to decide “whether it is indeed a new genus”.

On pairing the coronavirus data with a deer species such as sambar, Martin was similarly cautious: “The study would need to actually sample blood from these deer and identify the viruses in that blood to have a reasonable case that these deer are the actual hosts.”

It may not have been blood. Still, Daily Maverick’s additional investigations yielded a 2008 peer-reviewed study that had teased apart faecal samples from none other than sambar deer in a “wild-animal habitat” in the Midwestern US state of Ohio. And from the foetid depths of this fusty ejecta – sourced in the 1990s during an outbreak of winter dysentery – the Ohio study sequenced none other than the full-length genome of a coronavirus.

Next, it determined that the sambar genome was highly similar to bovine coronavirus (BCoVs). This, in turn, was “closely related to respiratory HCoV isolate OC43”. To you and me, OC43 is the coronavirus that causes the common cold.

The Ohio study, published in the high-impact Journal of Virology, added that “interspecies transmission and potential infection of humans with BCoVs has been observed”. Exotic species like deer may be particularly susceptible to bovine coronavirus from cattle, or vice versa, the study found: “Based on our data, ruminant host species exotic to North America may be more likely to acquire CoVs from cattle farms in the vicinity of the wild-animal habitat or from endemic wildlife species.”

The Leibniz study did not state if its potential novel coronavirus genus could infect humans – and here it is worth noting that one infectious coronavirus species in a host does not mean all coronavirus species in that animal are necessarily infectious.

“Any mammal species you choose to name would probably be a natural host of 10 or more distinct coronavirus species,” Martin offered. “We have found coronavirus-like sequences in metagenome studies of plants sampled in Western Cape fynbos.”

Hark! Does this mean that fynbos is hosting a killer coronavirus?

“No. It simply means that coronaviruses routinely infect all mammals.”

Ah.

To put it more plainly: “Mammals shit and pee a lot and mammals run around among the fynbos,” he said.

Preiser added that, “we know hundreds of coronaviruses yet only very few are able to infect humans”.

In other words, neither the Leibniz nor Ohio studies can be interpreted as saying that coronavirus lives in sambar across the deer’s natural as well as introduced ranges. It simply means that a species of coronavirus was present in introduced Ohio sambar in 2008; and that a coronavirus genus we have not seen before may now be lurking within sambar from Malaysian Borneo.

As the Leibniz study pointed out, deer species were widely detected in the leech samples – so the presence of both deer and coronavirus in the results could be entirely incidental.

“We could not reject that the occurrence of viruses and deer are independent variables,” the Leibniz scientists stated.

However, mentioning that coronaviruses have “spilled over from wildlife” before, this study added a conspicuous footnote: “[Deer] are regularly sold as bushmeat in wildlife markets.”

Low-hanging viral ‘fruit’

Comparing the blood meal DNA from leeches to known viruses, the Leibniz study homed in on gene sequences that latched on to distinct places of the evolutionary tree. Novel viral genera and species appeared to drop like, well, leeches from the forest canopy. Established viral empires emerged from some 60% of bulk samples.

This, according to the study, was “not unexpected as little is known about the virology of wildlife in Southeast Asia, where the leeches were collected”.

The study’s discoveries included unconfirmed genera similar to simian and feline foamy viruses (associated with HIV/Aids) and fish rhabdoviruses.

From natural waterholes in Tanzania’s Serengeti and Mongolia’s Gobi wilderness regions on the southern borders with China, the Leibniz team also gleaned water and sediment samples – four families featuring herpes, papilloma, retro and adenoviruses were observed. They were most likely associated with equid (horse-like) species.

In Tanzania, the team wrote, “both captive and wild zebras (Equus quagga) have been known to contract bovine papillomaviruses… it is likely that they are susceptible to different equine papillomaviruses.”

A ‘wonderful witches’ brew’

Investigating threat assessments in the Red List, Daily Maverick found that all other leech hosts isolated in this study – bearded pig (Sus barbatus), sun bear (Helarctos malayanus), Malay civet (Viverra tangalunga), Asian muntjac (“barking deer”) and zebra – were also persecuted species consumed in Africa and Asia’s bushmeat trade.

With the exception of zebra, which is eaten in Africa, “I can confirm all are eaten in Asia, although I don’t think bear-meat consumption is common – rather bear paws consumed in soup,” TRAFFIC communications head Richard Thomas told Daily Maverick.

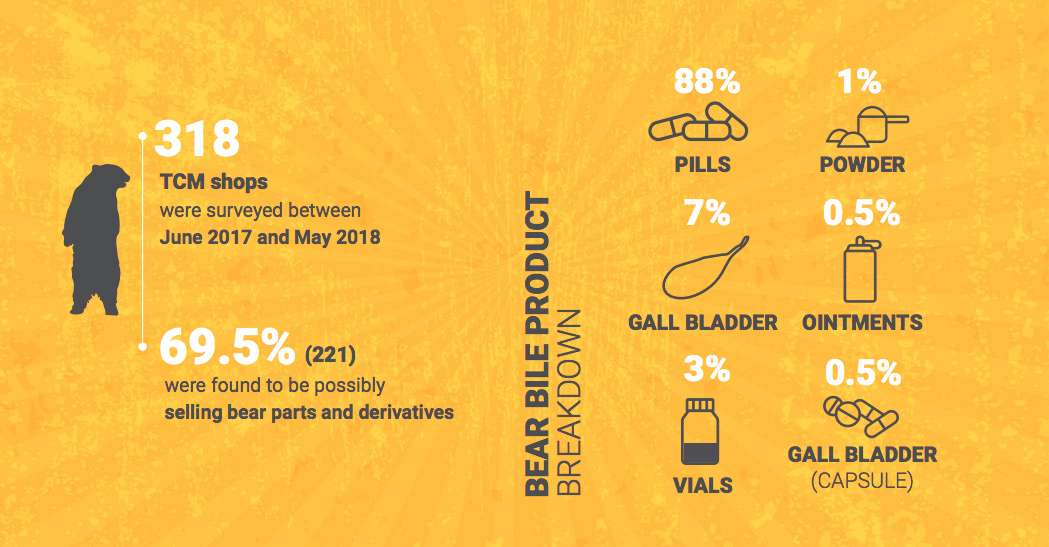

An inventory of the types of bear-bile products sold in Peninsular Malaysia from a 2019 TRAFFIC report. Pills were the most popular way of consuming bear bile, according to the report. (Image: An Update on the Bear Bile Trade, Peninsular Malaysia by TRAFFIC, the wildlife-trade monitoring network)

The Wildlife Conservation Society, a global environmental group, corroborated this: “Pig, muntjac and sambar meat are all still consumed for food in the region… more often today as luxury, often-illegal meat (certainly in the case of sambar) for the urban wealthy.”

Some species may even be dished up as proxies for others that are locally extinct, said the Red List: “In Vietnam, muntjac meat is now often served in wildlife restaurants as sambar, because real sambar meat is now so difficult to procure.”

Mapping the trade in bushmeat in 2016, the first global assessment on the subject found that some 300 terrestrial mammal species were consumed to the edge of their ability to survive. Published nearly four years before SARS-CoV-2 travelled to almost every continent, the study in the Royal Society Open Science journal sounded a clanging alarm:

“Hunting and butchering allow for high levels of direct contact of body fluids and are thought to have been important in emergence of Ebola, HIV-1 and -2, anthrax, salmonellosis, simian foamy virus and other zoonotic diseases,” the Royal Society study said.

“Given high rates of international trade in wild meat and human movement, this could easily have important short-term global health consequences.”

The intensity of human exposure to viruses was a modern thing, Preiser explained.

“Many of our regular viruses had an origin, long ago, in dogs, cattle, et cetera, and vice versa. Now there are so many of us and we are so mobile that any crossover is much more likely to have consequences than when the hunter brought home a duiker that died from Ebola,” he said. The hunter would die and infect his close family, but then the outbreak would “burn out”. By contrast, if that hunter hopped on a taxi to town today, Ebola could “spread like wildfire from human to human”.

Could the rogues’ gallery of new viruses pinpointed in the Leibniz study infect humans via their host animals? The Leibniz study did not say. However, the authors did imply that the viruses could mutate in ways that may not be appealing to people.

Firstly, they noted: “Most viruses are uncharacterised in wildlife and many evolve rapidly.”

Secondly, some host animals chosen by leeches emerged as probable intermediate vectors, rather than mere reservoir species, like bats. In short, the viruses seemed to have jumped the species barrier: for instance, torque teno virus first described in masked palm civet now seemed present in Malay civet. Leeches showing giant panda anellovirus seemed to have supped on the blood of the sun bear.

At least 60% of emerging infectious diseases in humans were of zoonotic origin, the Leibniz study pointed out – but mammal hosts have evolved to live with their companion viruses over millennia: thus, when zoonosis spreads, animals can hardly be blamed for being natural vectors of pathogen lines that precede the human story; nor for developing lowered immune systems widely associated with the crowded, stressful conditions of the wildlife trade.

It is “trade and consumption of bushmeat, especially in Africa and Asia” that have “increasingly played a role in pathogen spillovers into human populations”, the study explained.

This was a case of don’t shoot the messengers – diseased wildlife. They are the mere symptoms of rampant consumption and its triple-headed hydra: lax enforcement, habitat encroachment and markets selling wildlife and their products.

“Most virus emergence events are triggered by cross-species transmissions facilitated by the densification of human populations,” said Martin. He also cited animals kept for domesticated purposes and those consumed strictly as food, and the increased frequencies through which these relationships have become dangerously enmeshed with the human world.

It’s a “wonderful witches’ brew”, as Preiser called it – “wildlife capture, transport, farming and keeping together many species under terrible conditions”.

This awareness campaign by the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Global Wildlife Conservation group warns that ‘there is no risk-free trade or consumption of any wildlife whether they are wild-caught or farmed’. (Image: The Wildlife Conservation Society and the Global Wildlife Conservation group)

However, “matching viruses with their hosts is one of the biggest standing problems with environmental ‘viromics’ [the genetic study of a host and its viral species]. Such projects tend to find hundreds of new virus species, but they can only very rarely convincingly demonstrate the hosts of these viruses. Even when you identify a virus within the blood of a particular animal, there is always a reasonable chance that the animal is not the actual host,” said Martin.

There may even be some kind of genetic fault line separating a host and some denizens within its community of viruses.

“All the bacteria and other ‘healthy’ microbes that live on your skin and inside every internal surface of your body have their own viruses, virtually none of which are able to productively infect human cells.” Technically speaking, they are not human viruses. They do not have an invitation to get into the club.

Perhaps it’s more useful to think of a club host as a self-containing forest. The host organism – you, the house cat, or a sambar deer on an Ohio range waiting to be shot – is a wilderness unto itself.

Martin said it may be arbitrary, even dogmatic to assume that a virus would expand its host ranges and “begin infecting new host species”. The Leibniz study “has simply filled in some blanks with respect to describing the complement of viruses that infect some understudied wild animal species – it is assumed by any sensible virologist that almost every animal species will have a complement of 100+ (probably even 1,000+) distinct virus species able to productively infect it”. These are the viruses that live within the host mammal, rather than the microbe itself. They do have an invitation to get into the club.

Viruses are often “species-specific”, though, said Preiser: “HIV is a retrovirus that famously spilled over to us with disastrous consequences. Hunters from African rainforests have been found infected with various other retroviruses from primates; but none of these has taken off like HIV. Just being present does not mean a virus will find the path to spill over and, even when it does, it may not cause disease” or even “transmit efficiently among humans”.

As for getting excited about confirming a novel coronavirus genus, Martin said: “It is very interesting that they found the identified coronavirus sequence in so many different leeches.”

Even so, he dug his heels into the soils of viral discovery: “This study provides what is in many ways a blurry screen capture from a low-resolution security camera of one of the (very probably) tens of thousands of presently unknown coronaviruses we are pretty sure share our planet with us.”

More forensic byte than bark

From spotlighting novel viruses that could transcend species barriers to ferreting out new vectors, leeches may prove a useful auxiliary barometer of the animals we least want to see under the carver’s knife.

This method may even pave the way to describe a kind of virus multiverse, given how pitifully few of these pathogens are known to us.

“Non-invasive approaches to monitoring known and novel pathogens may be of particular benefit in ecosystems prone to viral emergence, many of which occur in areas where invasive sampling is challenging, such as tropical rainforests,” the Leibniz scientists wrote.

That’s where this study was “very interesting”, said Preiser, by “adding to our knowledge of the ‘zoo’ out there and using a novel approach”.

Leeches are cheap dates, too: standard invasive sampling of wildlife, such as darting and specimen capture, can be a high-cost, low-reward exercise. By contrast, the purveyors of leeches can simply count on the dirty work of foot soldiers patrolling a millennia-old ecosystem cycle. On top of this, researchers can siphon large DNA lumps from bloodmeals, especially when leeches are processed in bulk.

They are not universally available – blood-sucking leeches only dwell in certain rainforest regions, but other parasitic invertebrates such as mosquitoes or carrion flies could be equally effective data miners.

Crucially, plump with an organic dossier of forensic bytes, perhaps leeches can help warn humanity of the next outbreak before it strikes.

In a separate new preprint study on the complex origins of SARS-CoV-2 in several species, researchers from Chinese, European, UK and US institutions warned how difficult it may be to “identify viruses with potential to cause significant human outbreaks before they emerge. This underscores the need for a global network of real-time human disease surveillance systems like that which identified the unusual cluster of pneumonia in Wuhan in December 2019 and the rapid deployment of functional studies and genomic tools for pathogen identification and characterisation.”

The humble, if delightfully absurd, leech could prove a boon to humanity. Yet, we might have to wait to see if Grandma Moses and her blood-loving kin can truly be, to borrow the phrase from less inclusive times, man’s new best friends. DM

This article is strictly based on authoritative publicly available information and other expert sources. As required by the rules of the journal to which they submitted their findings for peer review, the authors of the Leibniz study were not able to provide Daily Maverick with comment on their research.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider