ART

Healing through family snapshots – Lebohang Kganye’s Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story

Photographer Lebohang Kganye travelled the country for a year, looking at the family photo album to grieve the loss of her mother.

Family photographs are called snapshots for a reason. The compound word suggests the speed and suddenness of a singular instant which, in the half-second it takes to press a button, is transferred onto film or digitally encoded to the memory card.

Click – her mother dancing to the radio.

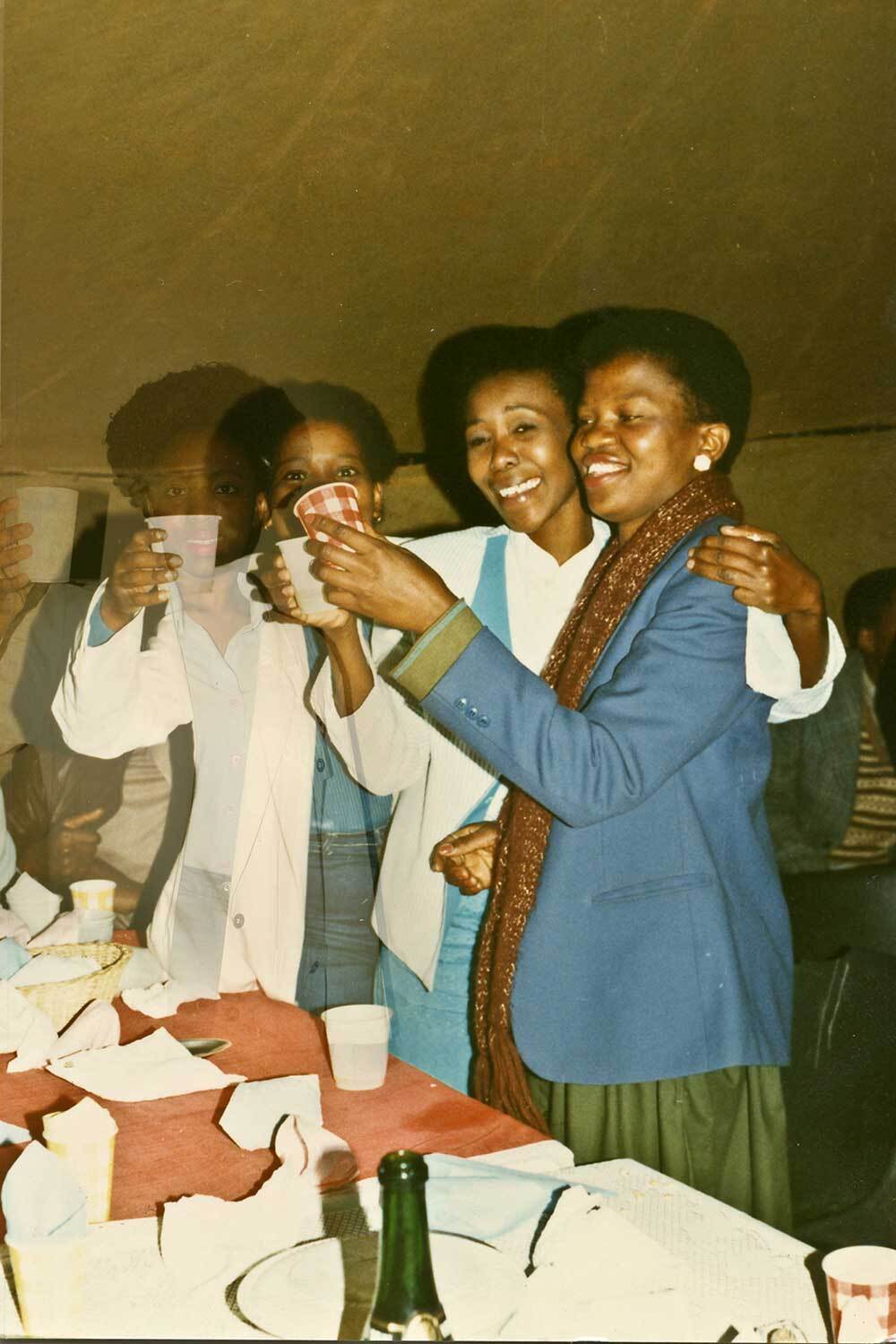

Click – her mother and friends toasting with plastic cups at a birthday party.

Click – her mother bringing a handful of food to her mouth at a braai.

These clicks then become the family archive. Preserved behind plastic in albums, they mark the who, what, when and where of personal history, a testament to lives lived and joys shared. They also represent a fantasy, an imagined existence, an idealised version of family that will outlast any reality. When the people, places, and things represented are no more – either passed away or moved away from – the images remain, lasting proof that they, indeed, were.

But what if those moments could happen again? What if they could be restaged anew? Not perfectly and exactly reproduced: the radio won’t play those same tunes and that specific birthday party and braai were one-time events. But what if the space between past and present – between mother and daughter – could be collapsed into a new snapshot, a new instant that bridges the space engendered by loss?

Ten years ago, Lebohang Kganye’s mother passed away. In 2013, three years later, the photographer sat down with her grandmother Maria to talk about history and begin answering those questions. She was the fifth recipient of the Tierney Fellowship at Johannesburg’s Market Photo Workshop, an opportunity for emerging artists to pursue a project over the course of a year with the support of a professional mentor and finances from the Tierney Family Foundation. The fellowship culminates with an exhibition, although Kganye had not mentioned a specific project or body of work to the organisation; she hadn’t yet envisioned one. The artist wanted to start with research and it began with Maria, her mother’s mother.

She was interested in her family’s history and her grandmother was the main source of information for tracing the Kganye story. Together they discussed a history of migration around South Africa as family members laboured on farms, were forcibly removed under colonial regimes and relocated after tribal wars. Over generations of movement the spelling of the family name changed, from Khanye to Khanyi to Kganye, the result of regional linguistic differences and the reconfiguration of identities by the state. This was the initial focus of her research, the family’s surname and history of migration. Maria gave her granddaughter different threads to work with, outlining a familial map across the country and connecting her with relatives. After these early conversations, Lebohang was ready to begin weaving it all together herself, taking a life-changing journey through their shared history, beginning in the Free State.

She travelled to the distant homes of relatives she had never known while growing up around the cosmopolitan hub of Johannesburg. On her visits, Kganye was shown photo albums in which her mother, Dimakatso, was a recurring subject. She had always been the connection to the extended family and their historical roots. Her mother was young in many of the images, around Lebohang’s age. She was sharply dressed in colourful ensembles and modern blazers, clothes that Lebohang recognised. She was familiar with some of the locations too and was discovering others for the first time on her trip. Her grandmother’s yard stands out, mostly unchanged after so many years, an archive of its own.

From these snapshots, Kganye’s photography project, Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story sprung to life. The title translates to “it’s my legacy” in seSotho.

“That work just came on its own, somehow it gave birth to itself through me,” she says. “That wasn’t what I intended doing, I was merely going through the family photo albums.”

Fittingly, Kganye means “light”. This is the key component of photography and though she initially sought to grapple with the history of the name, it was through pictures that Lebohang could address the loss of her mother and engage with the family’s past.

Ke bapala seyalemoya bosiu ka naeterese II by Lebohang Kganye (Image courtesy of the artist)

Kwana borayeng Phadima II by Lebohang Kganye (Image courtesy of the artist)

Moketeng wa letsatsi la tswalo la motswalle II by Lebohang Kganye (Image courtesy of the artist)

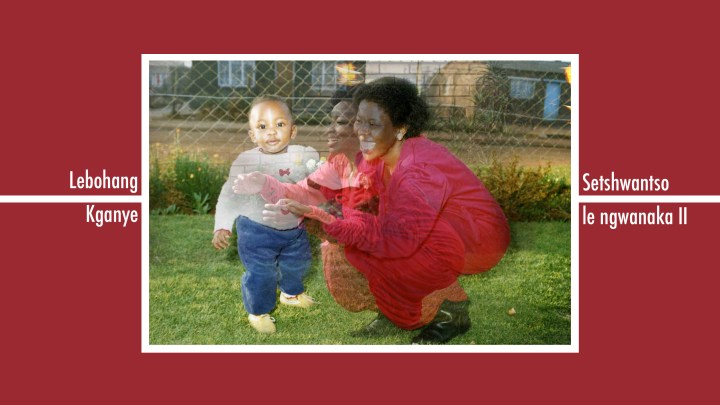

Setshwantso le ngwanaka II by Lebohang Kganye (Image courtesy of the artist)

She began playing the role of her mother and capturing it on camera, wearing the exact clothes she wore and posing in the same places. Her teenage sister, accompanying her on the journey, helped take the photos, Lebohang would set everything up ready for Tshepiso to press the shutter button. When their mother died Tshepiso was only 12 and Lebohang, at 20, had to step up as her primary carer. Part of this project involved reckoning with this new responsibility.

“Can I fill her shoes,” she asked herself.

She searched for answers in a very literal way, putting her own feet into her mother’s stylish heels and fluffy wedges for the photographs, challenging herself to do the job of parenting that Dimakatso had done so well, hoping to make up for her absence and fill the space she once filled.

There is an eerie quality to the pictures she produced by Photoshopping her own likeness on top of scans of the original snapshots. In the images Lebohang appears semi-transparent, floating beside her mother as an almost-perfect double. Sometimes we can see through Dimakatso, too, the figures blend into one another and their environment. Unfixed and fluctuating as they are, the pictures are open to multiple readings.

First, it seems Lebohang is a ghost, a spectral presence haunting her mother. But if she is still alive how could she be an apparition? Perhaps we are seeing the part of Dimakatso that lives in her daughter, made visible as she returns to moments from her past to be caught on camera once again. Maybe as Lebohang becomes her mother she is haunted by her own memories and grief. Or could it be this is the fluke of double-exposure on the camera, the result of capturing a subject on either side of a second? This way Lebohang becomes the proof of her mom’s immediate past, only made visible years in the future. It is mind-bending trying to figure it out. The pictures exist in an uncertain way, they bend time and space in illogical yet emotional ways, an appropriate metaphor for the shortfalls of memory.

While this project came organically to Kganye, it wasn’t necessarily easy to produce or exhibit.

“How do you safeguard against your practice,” she asks.

The answer is having faith in the healing made possible through facing trauma.

“There’s healing that comes from practice, from confronting pain. To a large degree Ke Lefa Laka was that,” she says, explaining that the year-long act of commemoration was therapeutic.

Family members from across the country came to the first exhibition of the pictures at the Market Photo Workshop. The project was well-received, a joyous, collective moment of tribute to a woman whose impact was felt broadly and deeply. A tribute that is reiterated with each gallery and museum showing of the work, which has enjoyed global audiences. Kganye, currently earning her MFA at Wits University, is taking time to reflect on what it means to share such personal content with the public. There is a challenge there but ultimately she sees the photographs as a site of healing. These images allow us to consider the nuances of loss, family, history and memory, themes which are both personal and universal. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider