VIETNAM WAR REVISITED

Kent State and Me — a personal memoir

May 4 was the 50th anniversary of the massacre of students at Kent State University, amidst student protests over the continuing war in Vietnam, and its sudden expansion into neighbouring Cambodia. These same protests brought me face to face with the police at my own university.

Well, come on all of you, big strong men

Uncle Sam needs your help again

He’s got himself in a terrible jam

Way down yonder in Vietnam

So put down your books and pick up a gun

We’re gonna have a whole lotta fun

And it’s one, two, three

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam;

And it’s five, six, seven

Open up the pearly gates

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why

Whoopee! we’re all gonna die

Well, come on generals, let’s move fast;

Your big chance has come at last

Now you can go out and get those reds

’Cause the only good commie is the one that’s dead

And you know that peace can only be won

When we’ve blown ’em all to kingdom come

And it’s one, two, three

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam;

And it’s five, six, seven

Open up the pearly gates

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why

Whoopee! we’re all gonna die

Come on Wall Street, don’t be slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go

There’s plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade

But just hope and pray that if they drop the bomb

They drop it on the Viet Cong

And it’s one, two, three

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam

And it’s five, six, seven

Open up the pearly gates

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why

Whoopee! we’re all gonna die

Come on mothers throughout the land

Pack your boys off to Vietnam

Come on fathers, and don’t hesitate

To send your sons off before it’s too late

And you can be the first ones in your block

To have your boy come home in a box

And it’s one, two, three

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam

And it’s five, six, seven

Open up the pearly gates

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why

Whoopee! we’re all gonna die….

The Fixin’ to Die Rag by Country Joe and the Fish.

Can it really be 50 years this week that the killings on the Kent State University campus in Ohio and then a few days later the lesser known but still deadly shootings at Jackson State College took place? The four deaths in Ohio and then the two further ones in Alabama, 10 days later, helped galvanise student opposition against the Vietnam War.

In turn, this anger, outrage and fear led to massive anti-war gatherings in Washington, DC, just a few hundred metres from the White House. Then-President Richard Nixon remained locked in the presidential mansion, complaining bitterly to staff and family that he could get no peace from the raucous sounds of the demonstrators protesting against what had become his war.

But why — and how — did the tragedies at those two otherwise unremarkable educational institutions become deeply symbolic of the larger national anguish in 1970? Part of the reason, of course, lies in the increasingly universal impact that the war was having on young Americans. By that year, the country had already been undergoing years of increasing agony over the ever-growing, never-ending, indeed, “unfinishable” war in Vietnam that was consuming the lives of thousands of Americans (not to mention many more South Vietnamese soldiers, Vietcong insurgents, North Vietnamese regular troops, and, of course, all those legions of innocent civilians caught in the middle of it).

By 1970, there were more than half a million American military personnel stationed in Vietnam. According to the advice of the generals, given to succeeding presidents and their aides, and repeated frequently over the years, the war would be winnable with just a few thousand more fighting men, or the expansion of bombing operations over North Vietnam, or some combination of both. But neither — or both — ever seemed to bring the promised land of a military success.

And so, in a throw of the military dice and aiming at a lateral solution, Pentagon planners had determined the way to both tactical and strategic advantage over their enemy was to cut off Vietcong supply lines that ran through southern Laos and on into Cambodia. Such a move would also disrupt the rear area supply bases and rest areas situated in the forests of the relatively sparsely inhabited eastern Cambodia used by Vietcong fighters and regular North Vietnamese army units fighting alongside them.

There was a problem for the Americans in this, however. Cambodia was an officially neutral nation in the conflict. For many years, its leader, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, had managed through an adroit diplomatic dance to keep the country out of the fighting in Vietnam (and Laos) by proclaiming Cambodia’s neutrality, even as his government turned a blind eye to the shadowy presence of Vietcong troops and their supply lines in Cambodia.

But apparently fortuitously for the Americans, early in 1970, Sihanouk was overthrown by a Cambodian general, Lon Nol, who was friendlier to US military adventures. Accordingly, American plans to attack the Vietcong in the Cambodian region known as the “Parrot’s Beak” and nearby territory in order to disrupt those supply lines and rear area rest and resupply zones could be activated. The area was named the Parrot’s Beak because of its resemblance on a map to such a shape, as it jutted into South Vietnam.

The initial attacks were carried out by South Vietnamese regular troops and then further attacks were carried out by American troops several days later. To opponents of the war in America, this was a demonstration that in the Nixon administration, the US military’s intention (despite Nixon’s campaign promise back in 1968 that he had “a secret plan for peace”) was to enlarge the zone of conflict in Indochina, rather than bring the ongoing war to a conclusion. Crucially for young adult men in America, together with the continual expansion of the contingent of US troops engaged in that war, this attack on the Parrot’s Beak made the possibility of being drafted to fight a war few wished to be part of that much more likely than it already was.

For most American males in universities and colleges, let alone for those in the beginnings of civilian careers, the idea of being drafted to slog it out in “The Big Muddy” was a terrifying prospect. The pressure was to somehow maintain a deferment from the military draft for as long as they were students, but such deferments only lasted as long as they could keep up with studies at a satisfactory pace. However, the draft boards throughout the country (one in each county) were becoming increasingly pressed to identify students who had dropped behind the required pace for any reason in order to meet their quotas for new inductees.

As word of the attacks on Cambodia spread across the country, spontaneous demonstrations also took place on many university campuses. This was the case even at schools where student political activism had previously largely been limited to smallish cadres of ultra-committed, anti-war students and supporters of varied left-wing causes more generally. Even at my university, at the University of Maryland, while anti-war demonstrations were rare, there were some activists. For example, a small group of such students had joined with other volunteers from other universities to go to Cuba to help cut sugar cane.

But despite the University of Maryland’s generally lethargic tradition of protest, as was the case, too, at Kent State University, the attack on the Parrot’s Beak brought out large numbers of students to find a way to protest the newly expanded war. In dealing with such demonstrations, nervous officials quickly sent in local police units to patrol those demonstrations and then, as things continued, inevitably reinforcements were called in to put a stop to things. Kent State University, in the small city of the same name, had never been seen as a location for mass demonstrations or protests previously.

At Kent State, the authorities eventually called up for active duty units of the Ohio National Guard (army reserve units not on active duty, many of whose members were in the National Guard precisely in order to avoid being drafted into the Regular Army and thus likely to be sent to Vietnam). After the campus had been the site of three days of demonstrations and a suspicious fire on a campus building, the National Guard was sent on to the campus. In Maryland, from 1 May, the state’s governor was similarly determined not to look soft on demonstrators and Maryland State Police riot control units were rushed into duty at the campus.

The undertrained National Guard troops moving on Kent State’s campus confronted a group of students and someone ordered them to open fire on the students. The shocking thing was that the troops in their formation, rather than using standard measures like tear gas, pepper spray or anti-riot movement tactics, were carrying loaded weapons which they discharged at the mass of students.

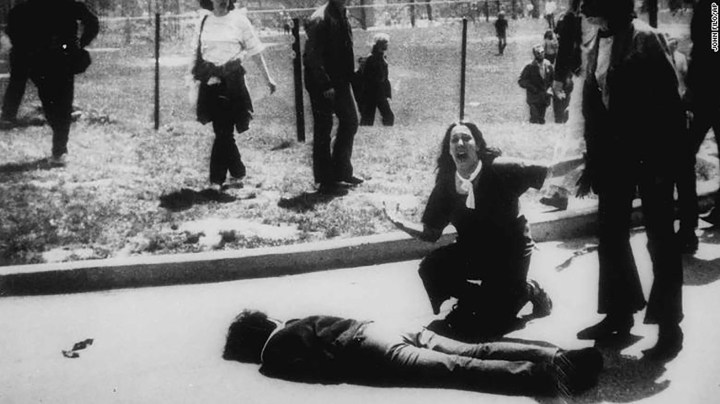

Four students were killed at close range, more were wounded, and the photographic documentation of the killing field became one of the most iconic images of the Vietnam War. (Three others are those of the South Vietnamese police chief shooting a Vietcong prisoner at point-blank range in the midst of the fighting in the Tet offensive of 1969; the young Vietnamese girl, her clothing burned off, fleeing the bombing of her village; and, of course, the final, humiliating evacuation of American personnel from the roof of an embassy outbuilding in Saigon.)

The deadly irony of the killings at Kent State University, of course, was that the National Guardsmen who killed the students were young men whose backgrounds were probably very similar to the students they had just killed.

The most famous image from Kent State University’s massacre, showing a young woman kneeling over a victim (not a Kent State student, but a wandering high school-aged student instead), once it had been published in newspapers across the nation, became a charged conduit for the anger and frustration so many were feeling about the war and the way it was being waged. Most terrifying of all was the realisation the war had now reached right into the calm precincts of a university in small-town America. It had something of the same emotional impact on Americans that, years later, the Marikana killings had on South Africans.

The two deaths at Jackson State University, a largely African American campus, meanwhile, had united anti-war protest together with the late stages of the country’s civil rights revolution. However, the graphic impact (and public outcry) was never quite the same as those deaths at Kent State less than two weeks earlier. Jackson State received much less media coverage and generated less outrage, given that it had come just after the earlier deaths. Kent State became the symbol.

Looking back at the significance of the shootings, CNN reported, “Fifty years ago today, the Ohio National Guard fired on Kent State University students as they protested against the Vietnam War. Four students were killed. Nine were injured. The incident on May 4, 1970, now known as the Kent State massacre, dramatically changed the nation. It prompted a nationwide student strike that forced hundreds of colleges and universities to shut down.

“Life magazine and Newsweek dedicated cover stories to the incident. The New York Times famously showcased the now-iconic photograph of a young woman screaming as she knelt over the body of a Kent State student. The shootings turned the tide of public opinion against the Vietnam War, and some political officials even argued that it played a role in the downfall of the Nixon administration. Today, the incident symbolises the political and social divides brought on by the Vietnam War.”

In my own circumstances, three days before the Kent State killings, I had had my own encounter with the violence that too often arrived as an accompaniment to anti-war protests. I wrote about it some years back, saying, “Forty-five years ago, the Maryland State Police assaulted me during an anti-Vietnam War/anti-Cambodian invasion protest as the cops tried to end a roadblock of a major East Coast North-South thoroughfare adjacent to the University of Maryland’s main campus… Knocked down by police and given a nasty head wound as a bonus, I was summarily bundled into an ambulance and sent to a local hospital to be stitched up, instead of being arrested like dozens of other students were that afternoon…

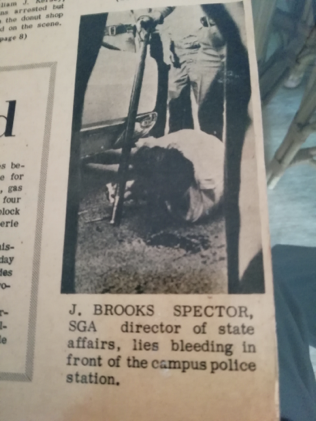

The U of Maryland student newspaper, The Diamondback, published on 4 May, after a weekend of demonstrations. Note the tear gas canister being fired into a student residence by police…

The writer on the ground after being beaten. (SGA is the American equivalent of the South African usage for a university’s SRC.) In my case, I was responsible for trying to maintain connections with the state government — the governor’s office, the state legislature, and so on, in a contentious time.

“Not surprisingly, the university disavowed any responsibility for the costs since my injuries happened during a student demonstration that had turned ‘violent’. Meanwhile, the police declined to even consider any question of liability. Their spokesman insisted to my face that the whole thing had been my fault for falling against a police cruiser that was parked on the street when the police charged the student protestors.”

After the demonstrations, protests and running battles with the police had continued for days on our campus, and especially after news of the Kent State shootings had reached people. Eventually, the governor of Maryland decided it was important to end the demonstrations on the campus in order to show who was in charge and he ordered in the National Guard to bring the protests to a final, but very sullen end.

As a personal irony, some months later, I received a mailed notice that I was about to be drafted and so I hunted frantically to find an opening in any army reserve or National Guard unit that could take me as an enlistee, rather than become cannon fodder for the fighting in Vietnam. The war itself only came to its conclusion years later, in 1975, when North Vietnamese regular army and Vietcong units crashed their way into Saigon and the surrender of the remaining South Vietnamese military units.

The agonies of many Vietnamese continued for years to come, including the efforts by thousands of refugees and “boat people” to flee the country of their birth. As for the two universities in America, Kent State and Jackson State, both now have memorials marking the locations where students died in the process of exercising their rights to free speech. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider